‘Fake’ works by Botticelli and Van Gogh found to be priceless originals

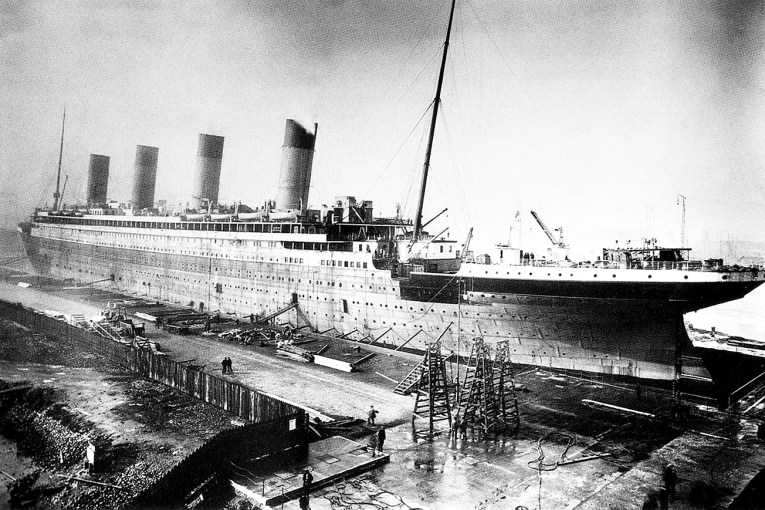

A conservator from English gives the rehabilitated Botticelli, wrongly thought to be a fake a much needed clean. Photo: English Heritage

If you’re thinking the Goya in your foyer is a charming fake – a declared homage if you’re touchy – maybe call in an expert for a closer look.

In recent weeks, two paintings by legendary artists that were thought to be knock-offs, have in fact proved to be multimillion-dollar genuine articles.

This week, a painting long thought to be a later imitation of Sandro Botticelli’s famous Madonna of the Pomegranate has been revealed to be a rare example by the artist’s own workshop, according to an English Heritage press release.

Cleaning leads to discovery

The discovery was made while the painting was being cleaned by the charity’s conservators.

The work’s true colours – hidden under more than a century of yellow varnish – will be revealed when it goes on display at Ranger’s House in Greenwich on April 1.

Hopefully, as crowds throng to see the rehabilitated masterpiece, some clown in period costume doesn’t bounce out of the shrubbery, yelling: “APRIL FOOLS!”

According to the statement, the painting – Madonna della Melagrana (c.1487) – was bought by diamond magnate Julius Wernher in 1897.

It’s considered the closest version of the famous masterpiece by the Florentine master Botticelli, now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

A colourful painting with a sad theme

Showing the Madonna and Christ Child flanked by four angels, the title refers to the pomegranate that is held by the Madonna and Child to symbolise Christ’s future suffering. (The pomegranate actually goes back to Greek mythology, and its standing as food consumed by the dead in Hades.)

The painting was assumed to be a later imitation because of its variations in detail to the original and the thick yellow varnish that concealed the quality of the work.

But X-Ray testing, infrared studies and pigment analysis finally revealed the painting is from the workshop in Florence where Botticelli created his masterpieces.

A closer look at all the facts

Rachel Turnbull, English Heritage’s Senior Collections Conservator, said in the statement: “Being able to closely examine and conserve this painting for the first time in over 100 years has really given us the chance to get up-close and personal with the paintwork.”

A detail of the painting now confirmed to originate from Botticelli’s workshop in Florence. Photo: English Heritage

“I noticed instantly that the painting bore a striking resemblance to the workshop of Botticelli himself; stylistically it was too similar to be an imitation, it was of the right period, it was technically correct and it was painted on poplar, a material commonly used at the time.”

After consultations with our colleagues at the Victoria and Albert Museum and the National Gallery London, the true origins of the painting were confirmed.

It was not unusual for popular paintings by Botticelli to be commissioned again by other patrons – and these works were often reduced in size, composition or detail.

Botticelli (1445-1510) employed a number of assistants who would execute large parts or even whole panels of his paintings to help him meet demand.

Maybe it’s not sunflowers or a starry night, but this somewhat sweet but dowdy bowl of fruit is still a genuine Van Gogh, and no doubt worth a bob or two. Photo: supplied

Meanwhile, last month, a small still-life that for early 60 years baubled the walls of the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco has been confirmed as a genuine work by Vincent van Gogh.

The painting, Still Life with Fruit and Chestnuts, was donated to the museum by a couple in 1960 and suspected to be by the Dutch master.

But several experts pooh-poohed the claim. However, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam determined that Van Gogh painted the rather dowdy fruit bowl – perhaps on a blue day – in 1886.

The news has been somewhat muted, as the confirmation occurred last year, but wasn’t reported for months.

In a further discovery, the experts found there was a portrait of a woman hidden underneath the still life.

The often sad artist – whose works are now priceless – often reused his canvases because he was too poor to buy new ones.