Why the housing credit fantasy can’t last forever

When Treasurer Joe Hockey said this week there was no chance of a residential property bubble bursting, he was telling homeowners a familiar and reassuring story.

Mr Hockey told journalists:

Bubbles have burst in real estate when there has been too much supply and not enough demand … The best way to respond to elevated house prices is to increase supply. And what we’ve seen is a massive increase in the amount of housing construction in the last year, up 18 per cent.

So supply is increasing at its fastest rate in years thanks to a construction boom. But not so fast as to send prices backwards?

Quite possibly, though there are signs the demand side of the equation is also changing. As described previously, rental vacancy rates are creeping up in every city except Melbourne, and the average number of persons per household has also increased slightly in recent years.

• Economic green shoots, but in all the wrong places

• Making retirees richer the old-fashioned way

• Flashing red signal for house prices is getting brighter

That is, the supply-demand dynamic is not simply a function of the number of people and dwellings in Australia, but is also affected by people’s propensity to live together.

And with the RBA estimating that the mining boom inflated national incomes by around 13 per cent at the peak of the boom in 2011, it’s easy to see how a few people have realised since then that it’s time to move back in with relatives or house-share.

So while Mr Hockey might be right that there’s no ‘burst’ on the horizon, there is a strong possibility that house prices will drift sideways or even fall on his watch.

The two key drivers of that development are wages and available credit.

First, wages. The last ABS wage-price index results showed wages increasing at 2.3 per cent annually, with this year’s March quarter result being the lowest rate of growth since the sharpest point of the GFC in the September quarter of 2009.

At least that’s a real increase in wages – that is, it’s ahead of the last CPI measure of inflation, which was an incredibly low 1.3 per cent between the March quarters of 2014 and 2015.

It’s that last figure that is keeping the RBA up at night. Its mandate is to keep inflation between two and three per cent, and so it is keeping the official cash rate at an emergency setting of two per cent to encourage people to borrow and spend more.

Unfortunately, for months that has mostly helped borrowers bid up the price of residential property, particularly in those two bubble towns of Sydney and Melbourne.

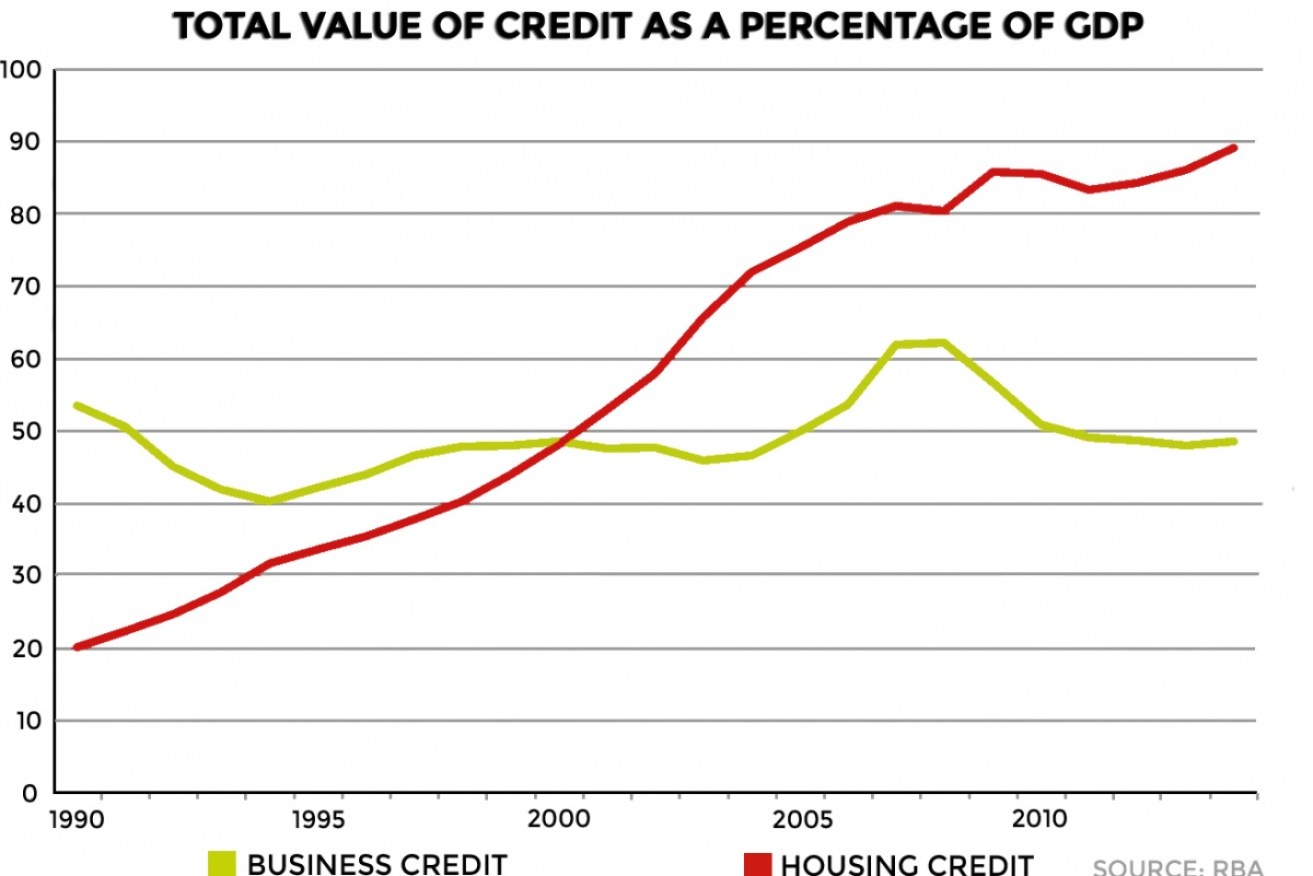

But that is not where borrowing and spending should be directed. The great imbalance of the Australian economy is shown quite clearly in the chart to the right – namely that over the past 25 years we have tied too much capital to the ‘unproductive asset’ of housing, and too little to the productive entities we call ‘business’.

Houses contribute to the economy by turning out happy, healthy workers who labour to create the goods and services Australians consume, or to create tradable goods and services to help pay for imports.

And yes, Australian dwellings have become fancier, better structures over time so are worth more – just as an Audi is worth more than a Hyundai.

But that’s not in itself enough to drive the stock of housing debt from 20 per cent of GDP in 1990 to around 90 per cent today.

That huge run-up in debt was based on a number of factors. We’ve had nearly a quarter of a century of positive economic growth, nearly a decade of booming resources prices and investment, a global credit bubble that did not deflate as much in Australia as elsewhere and – when the GFC threatened to halt the growth of housing credit – waves of federal and state government hand-outs to help first home buyers get onto the housing ladder.

What’s forgotten in that long-term story is that each new generation has to direct an ever-larger proportion of their pay packets to servicing debt.

The point at which that decades-long trend finally ends may or may not come on Mr Hockey’s watch, but it cannot be delayed forever.

Prime Minister Tony Abbott, when quizzed about a ‘bursting’ of the bubble this week, was more vague that Mr Hockey in his answer. He merely said he wanted “housing to be affordable but nevertheless, I also want house prices to be modestly increasing”.

If, by that, he means prices increasing in line with wages growth for the first time in decades, he may just get his wish. But if he’s hoping to see housing debt increase further as a proportion of GDP, he’s flogging a horse that probably has very little life left in it.

Australia’s rebalancing away from a heavy dependence on the resources sector comes at time when we must also rebalance away from a long property and credit boom.

That doesn’t have to mean a bubble will ‘burst’, but it does mean the end of an era in which Aussie pay packets were assumed to be able to service unlimited amounts of debt. If anything is bursting, it’s that fantasy.