Housing myths have been stretched to the limit

In their own distinctive ways, Glenn Stevens and David Murray are again warning us that our finance and economic systems are dangerously out of balance.

Reserve Bank governor Stevens told a Sydney forum on Tuesday that “it’s important people realise how much risk is being taken on” by investors chasing decent returns on their money, but that “in the real economy risk taking … is a little on the subdued side”.

Investors have looked to high-yielding shares and residential property as ways to get decent yields in an era of otherwise desultory returns.

• Boom or bust: the property market in 20 years’ time

• Why your dream job may not be so dreamy

• Six tax hikes guaranteed to upset everyone

How neat – bank stocks have seemed attractive, just as the property boom they are funding looks attractive. Just don’t think about the risk of one causing the other to tumble.

Meanwhile, businesses are baulking at investing to create more jobs, or at least longer hours for existing employees. The RBA has held rates at record lows hoping to stimulate this process, but with little success so far.

Reserve Bank governor Glenn Stevens: “It’s important people realise how much risk is being taken on.” Photo: AAP

As chair of the government’s Financial Systems Inquiry, Mr Murrary looks at the coin from the other side. He asks whether our banks could survive a downturn and property rout, and whether the Australian taxpayer would have to bail them out.

His gripe is that while banks around the world have bulked up their capital reserves to help them cope with a downturn, in Australia this has mostly been achieved by smoke and mirrors.

Australian banks have met internationally agreed ‘capital adequacy ratios’, but not so much by increasing the capital reserves they could draw on during a crisis, but rather by reducing the ‘risk weightings’ they give to the loans they hold on their books.

Put another way, if you want to have eight per cent of the value of the loans you’ve made in your pocket, you can put aside more of your earnings … or exaggerate the value of the loans themselves.

That ‘exaggeration’ relies on the risk weightings given to loans. And in the mortgage lending sector in particular, Mr Murray thinks the big four banks have taken an over-optimistic view of how many mortgages could fall over if there was a financial shock.

All of this will be a moot point if there turns out to be no ‘shock’ in the years ahead. But how likely is that? Commentators such as David Llewellyn-Smith at MacroBusiness remind us of global dangers such as “a European accident, China’s adjustment accelerating or the US stockmarket imploding on minimal interest rate hikes”.

David Murray believes the banks are over-optimistic of how many mortgages could fall over if there was a financial shock. Photo: AAP

But there is another, internal trigger for a crisis in the housing market; simply, the extent to which sectors of the housing market are already over-bought as western Sydney was in the early 2000s. The Anzac Day weekend, for instance, saw Sydney’s astonishing property run continue, with auction clearance rates hitting 95 per cent in the western suburbs and 91 per cent for the city overall.

Investors joining that frenzy are chasing longer-term capital gains that (they hope) will outperform other asset classes. The problem with that view is that it’s based on a long bull-run in the property market that it is hard to see continuing.

The industries that profit from this ongoing property splurge – the finance, insurance and real estate, or ‘FIRE’ sectors – do a great job of talking up house prices based on the well-established story of ‘demand outstripping supply’.

But that story is overdone. While it’s true that the number of new residents in Australia is rising more quickly than the housing stock, there are demand factors at work that are not fully understood.

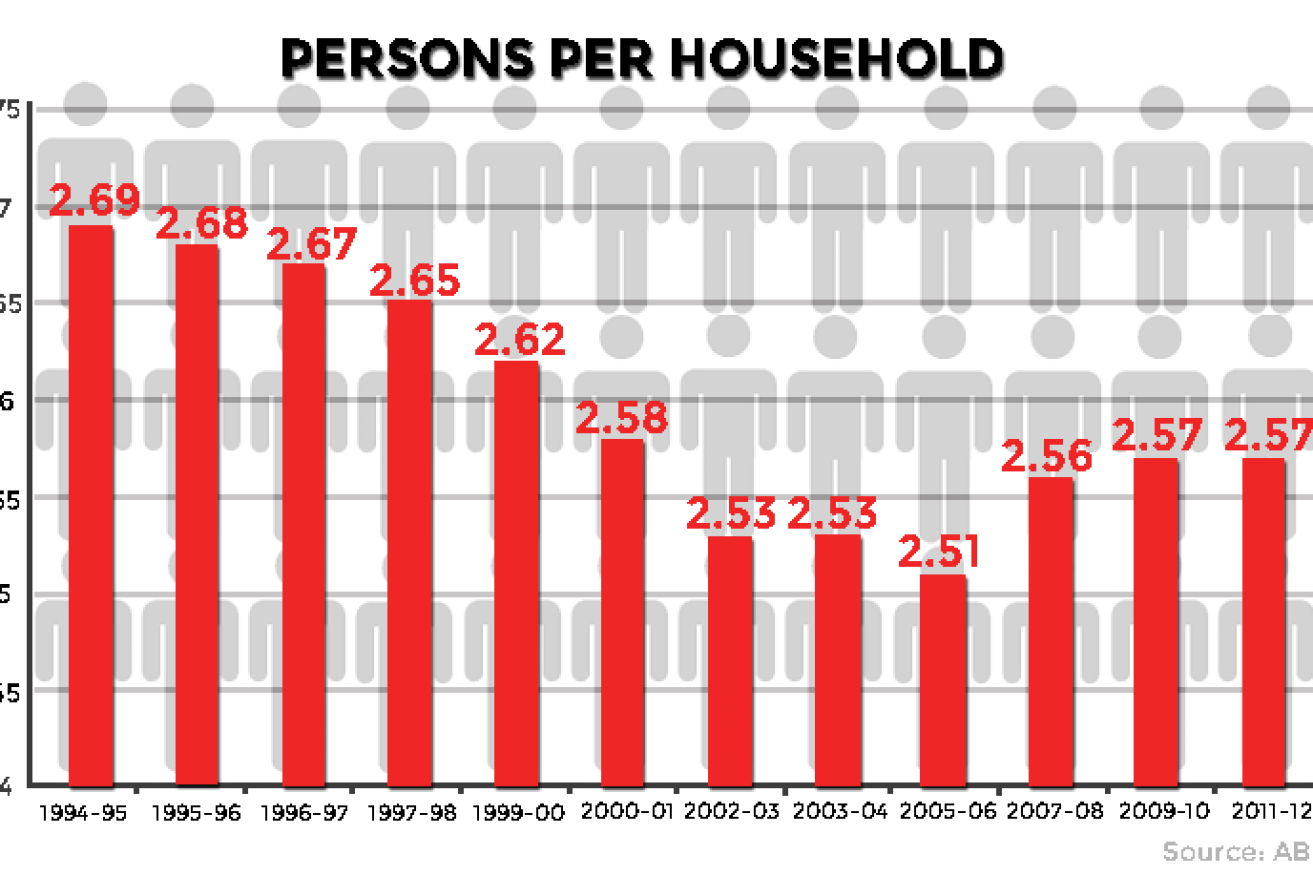

One of the most perplexing data sets compiled by the Australian Bureau of Statistics is the ‘persons per household’ data, presented in the chart below. It is only released every two years, so the data for 2013 and 2014 won’t be seen until the end of this year.

The chart shows a couple of curious things.

The chart shows a couple of curious things.

Firstly, although exaggerated on the scale above to make it more readable, the data is actually pretty flat overall. Australia’s long housing boom based on a ‘shortage of supply’ began in the mid-1990s, and yet by 2012 there were still fewer people per household than when it started.

Secondly, the long but gradual decline in household size turned around in 2006, just as house prices really started to heat up.

The point is, a ‘supply shortage’ is not as rigid a structural problem as the FIRE industries insist, and needs to be set against the changing patterns of demand.

Sure, people might not want to share houses to the extent they did in the 1990s, but as wages flatline and house prices continue to surge, a growing number of people will change the demands they put on the sector – youngsters living at home longer, more house-shares, and home owners taking in lodgers, for instance.

The price of houses has always been a bit different to most things Australians consume, because in addition to ‘supply’ and ‘demand’, the price is also set by ‘available credit’.

Well Glenn Stevens and David Murray are warning that available credit is pushing things too far. Supply, we know about. But changing patterns of demand could be the wildcard that tests investors, and the banks that fund them, to the very limit.