Michael Pascoe: Two or three RBA rate hikes – that’s the stage-three tax cuts

The Morrison government's tax cuts are having flow-on effects on inequality, writes Michael Pascoe.

Spare me anyone again asking the Prime Minister or the Treasurer if the stage-three tax cuts will go ahead.

They’ve told us and told us and told us again that, yes, the government’s position remains unchanged, so nobody should be in any doubt about what happens to the tax scales on July 1.

Of course that doesn’t stop Coalition spokespeople making inane claims for the sake of having said claims faithfully reported by stenographers or the odd shock jock sounding like he pays more attention to those Opposition claims than what the government promises.

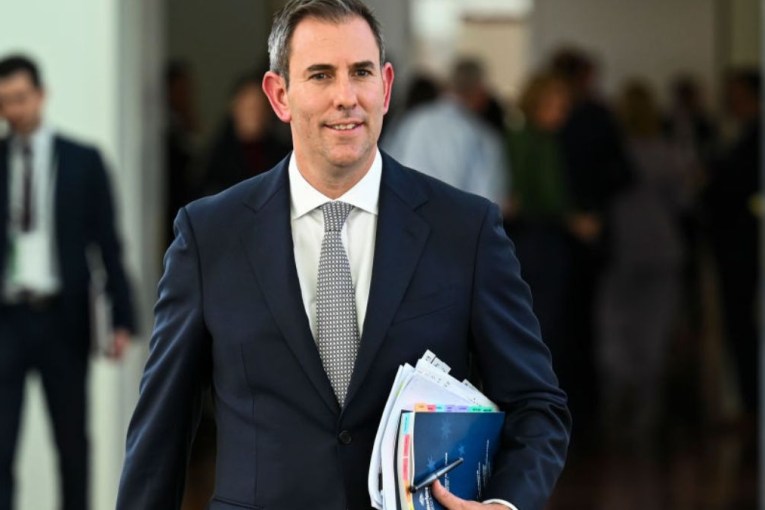

In any event, there are more interesting aspects to speculate upon, such as: (1) what other spending/tax adjustments Dr Chalmers is planning for the budget to soften the inequality charges against the stage-three cuts; (2) what might be the RBA interest rate equivalent of the extra $21 billion stage three will pour into people’s pockets over the new financial year; and (3) what the inevitable next step in flattening our tax scales will be when the Coalition is next in power.

Having wrestled with (2) and numerous charts and numbers and seeking more qualified opinions, it is easier to frame that question as: How many times would the RBA have to hike rates to suck a net $21 billion out of demand?

Turns out that is still a very complicated question – maybe why the RBA and Treasury haven’t been game to address it – but my rough guesstimate is certainly two and maybe three rate hikes, about three-quarters of a per cent on home mortgages. I’ll come back to that.

Countering inequality

As for (1), Anthony Albanese gave a hint of “watch this space” on ABC radio on Monday.

While using the same weasel words as his Treasurer to sidestep the inflationary impact – “it’s factored in” means nothing – he was quick to follow confirmation of the stage-three cuts with “inequality is an issue and the government has looked at ways in which we can improve that position”.

It’s something independent economist Saul Eslake has picked up on, too.

“I suspect they might be thinking about is whether they do anything else on top of that because as the legislation currently stands, the benefits of tax cuts to people on medium incomes is relatively small,” he said.

“What I think the government may be contemplating is perhaps in addition to what has already legislated, they might find a way of giving people on more modest incomes something out of additional tax cuts they otherwise wouldn’t get and they will claim that as a form of cost-of-living relief.”

Treasurer Chalmers has previously tried to put the inequality aspect of stage three in a little perspective by pointing to what else the government has been spending money on – there’s a lot more to the annual budget than that $21 billion going overwhelmingly to the better paid.

You can bet on the May budget speech adding up what’s been done with child care, rental assistance, aged-care pay, energy bills, Medicare et al coming to substantially more than $21 billion – mostly subsidies and payments those earning $200K+ a year don’t get while paying a fair whack of tax so other people can.

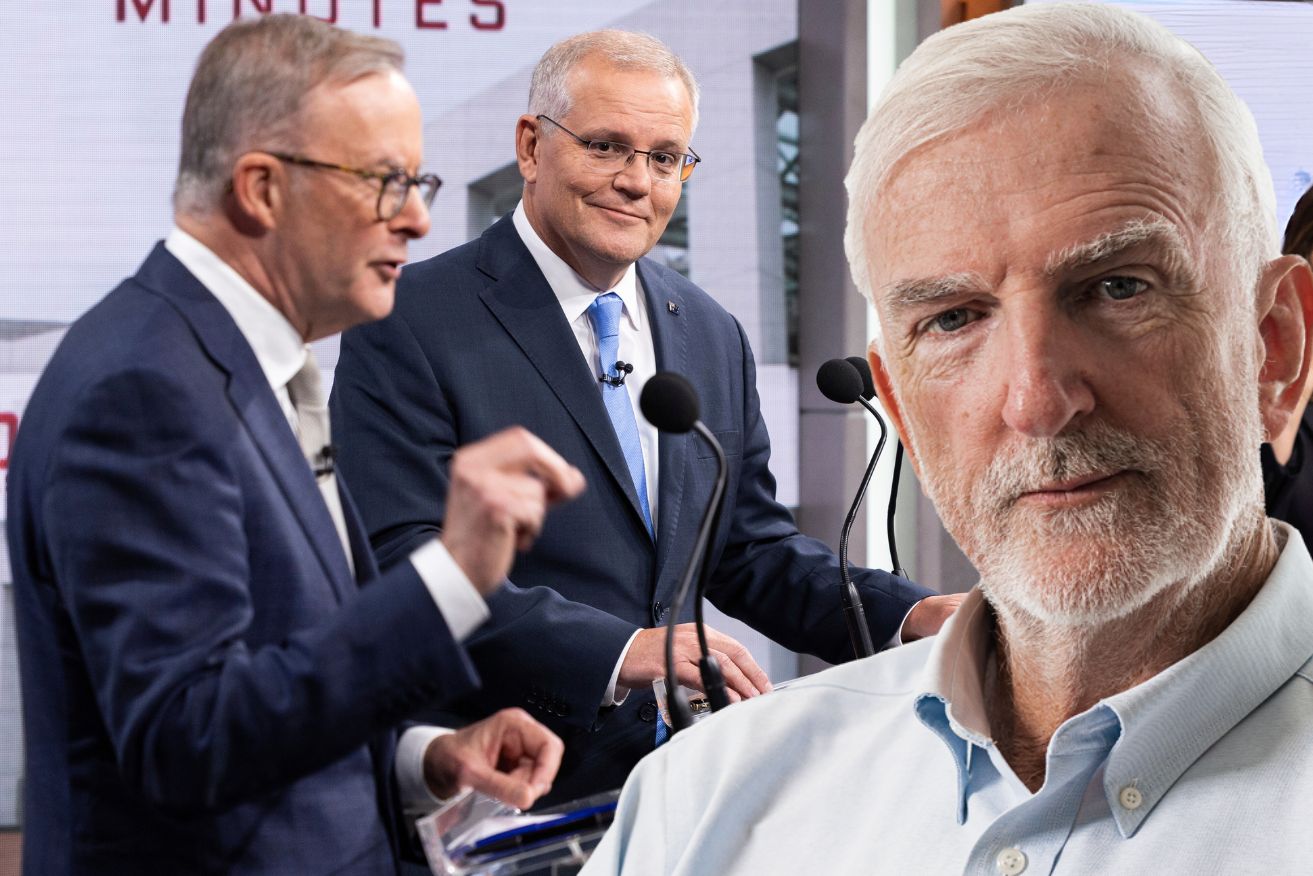

In fairness to Mr Albanese dealing with the stage-three political trap Scott Morrison set in 2018 ahead of the 2019 election, we can get caught up in arguing the progressive/regressive aspects of individual policies instead of considering the whole.

Bigger picture

The inability of our politicians to even mention the possibility of increasing or broadening the regressive GST is a prime example, the Left in particular given to conniptions at the thought.

Yet Scandinavian countries, the world’s most progressive, the ones with the least inequality and best social welfare systems, have bleeding-from-the-eyes value-added-tax rates of 25 per cent, demonstrating how it’s not just about how revenue is raised, but what is done with it on the other side of the ledger.

That’s the political challenge now for Albanese/Chalmers in the May budget – selling it as something for everyone, not only Scott Morrison’s cunning and ideologically-driven stage-three plan.

(In doing so, they’ll be hoping people have forgotten the loss of the low-to-middle income tax offset – or could the reintroduction of something along those lines be the required sweetener?)

It’s not all over

It’s the ideology element that brings up question (3). Having a single marginal tax rate of 30 per cent from $45,000 to $200,000 will not be the final stage of desires to flatten our progressive system.

The curtain has not come down on the age of neoliberal policy dominance ushered in by Reagan and Thatcher.

The push continues for the wealthy to pay less tax and everyone to receive fewer government services. Just ask Gina Rinehart and the Institute of Public Affairs, or any of the right-wing American lobby groups they mimic.

It takes little imagination to see the next campaign: Our tax scales are so unfair, soaring by 50 per cent from 30 cents in the dollar to 45. Suddenly losing nearly half of every dollar they earn over an arbitrary level is a massive disincentive for our most talented people to work – we really need to reduce that 45 cent level.

You heard it here first – and never mind that Australians actually pay relatively little tax compared with most developed countries.

Complicated answers

And (2), the ratio of RBA rate hikes to $21 billion of extra demand in the economy? It is fiendishly complicated to calculate thanks to the many variables and unmeasurables. The human factor means it’s likely the RBA and Treasury computer models could not provide an accurate answer – just as they can’t forecast anything accurately.

But as a rough starting point, the Australia Institute’s David Richardson turned to APRA figures on banks’ credit charges since the RBA started raising rates. Allowing for lags on different loans, that indicated 100 points of cash rate increase (four of the RBA’s usual 25-point hikes) resulted in $48.4 billion in extra loan payments to banks.

Then it gets harder. Such a broad figure would have to be adjusted to deduct loans to non-residents and then adjusted for the tax deduction afforded business and housing investment loans. (The latest APRA figures show about $1.7 trillion in loans with tax-deductible interest and $1.5 trillion for households that can’t deduct.)

On the other side of the ledger, there are depositors receiving bigger interest payments, but transaction and at-call accounts only received about half the increase in the cash rate, unlike term deposits. And there is tax to be paid on the increased interest received.

The Australia Institute paper again tried to get a handle on it via the big picture of what banks paid out in interest, according to APRA – a theoretical extra $45.2 billion a year per 100 basis points on the cash rate.

There are problems with that figure, the first one being that it doesn’t pass the commonsense test. If the net effect of a 100-point increase in interest rates is to take only $3.2 billion out of the economy over a year, monetary policy is an even bigger waste of time and effort than anyone ever guessed.

My admittedly extremely rough guesstimate is that you could conservatively halve the bald interest-collected figure and then add on about a quarter of the interest-paid to get the contractionary impact of maybe $36 billion per 100 points – $9 billion per RBA hike.

So, if the RBA wanted to take the $21 billion of stage-three tax cuts out of the economy, it would have to hike more than twice.

As it turns out, the economy is slowing, the RBA has done hiking rates and, on the forecasts of Treasury and the RBA, we are likely to need that stimulus to prevent unemployment rising too much.

Could interest rates come down a little sooner and faster later this year if the $21 billion wasn’t there?

We’ll never know – and neither the RBA or the Treasury seem interested in speculating about it.

After all, “it’s baked in”.