Michael Pascoe: RBA needs more businesses to fail

The RBA needs more pain to control inflation, Michael Pascoe writes. Photos: TND/AAP

Everyone talks about what unemployment rate the RBA regards as “full employment”. (Spoiler alert: it’s now 4.3 per cent, a little less than it was three months ago.)

Nearly everyone overlooks the rise in business failures and bankruptcies required to get there.

There are already headlines months old about “the highest business failure rate since the GFC” but that is going to get considerably worse this year.

What’s more – and what’s not polite to say – is that the economy needs it to get worse, the RBA needs it to get worse.

Worse to come

Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock specifically rejected the “needs” word when I asked if the bank needed a further 10 per cent rise in bankruptcies and business failures to achieve its inflation target.

“I wouldn’t use the word ‘need’ or ‘want’, or ‘like to see’, I wouldn’t use any words like that,” Bullock said.

But what’s in a name, or word?

Putting the preferred language aside, the RBA is looking to an increasing number of businesses hitting the wall after being propped up by the Treasury’s largesse, extremely low interest rates and the Australian Taxation Office extending them credit.

The bank believes that is starting to happen. It has to happen more.

Governor Bullock said she did not have expectations of a particular rise in business failures “but we are seeing the rise to more normal levels”.

The role of zombie or “propped up” businesses did not feature in the governor’s attempt to explain the conundrum of lowering its unemployment forecast a touch on Tuesday while also lowering its (already weak) economic growth forecast for this year and consumption was going backwards.

‘Interesting question’

When a weak economy weakens further, unemployment is supposed to worsen, not improve, according to the textbooks.

She said what’s going on in the labour market was “a very interesting question” for which she did not have a full answer.

Partly it was that many of the jobs being created are in essential services – education, health – and thus immune to the cycle. There was speculation that businesses were only just being able to hire the workers they had been looking for when the labour shortage was at its worst and perhaps there has been an element of “labour hoarding” – employers hanging onto staff they might otherwise shed as they didn’t want to be caught short if business picked up, as happened coming out of Covid.

“Unemployment” is a straightforward word. The RBA preferring to talk about “full employment” rather than the NIARU (non-inflation-accelerating rate of unemployment) strikes me as a little euphemistic as well as a means of walking away from a figure which the bank has only even known about in hindsight.

Tuesday’s quarterly statement on monetary policy spelt out what unemployment rate the bank thinks is compatible with getting inflation down into its 2 to 3 per cent target zone in the second half of next year – 4.3 per cent, one notch lower than it forecast three months ago.

But the required business failure rate is not spelt out and apparently not forecast.

In such a vacuum then, given that the RBA wants a 10 per cent increase in the unemployment rate from here, it looks reasonable it would expect a 10 per cent or so increase in employers failing from the “more normal levels” we’re seeing now.

But the RBA doesn’t “expect” about such things. Instead, the benefits of businesses failing is smothered in euphemisms.

Productivity dilemma

The SoMP blamed part of weak productivity growth on “slowing capital and labour reallocation”. The governor said that, yes, we need “business dynamism” to get productivity improvement.

That all means the marginal, least-productive businesses failing, going broke, freeing up labour and capital for more productive and new businesses.

That’s the harsh reality the business cheer squad in particular likes to ignore: If you want to improve productivity, wipe out the least productive.

Instead of being honestly explained as a necessary part of the Darwinian thing that is capitalism – however tragic and painful it is for the individual business owners – stories of rising failures are inevitably painted as somehow being a failure of government policy.

Sending businesses broke is a less-spoken-about part of the monetary policy transmission mechanism.

As the governor put it, a lot of money went out the door from government to help households and businesses in the pandemic. Along with rock-bottom interest rates, businesses in aggregate saw balance sheets improve markedly, coverage rates improved, debt servicing went down.

Now businesses that were propped up by Treasury and RBA policy are starting to run out of prop, plus the ATO is looking for the repayment of debts that were let run.

Return to ‘normal’

That the return to “normal” is only starting with more than “normal” to come is one of the two key reasons the economic hawks calling for more interest rate rises this year are divorced from reality.

The other is that the impact of the past two rates hikes are yet to be felt – they’re still coming down the mortgage slippery dip.

That tends to be overlooked by private sector economists getting their names in print for recommending or forecasting more rate rises.

Chanting “you’ve increased the cash rate to 4.35 per cent but inflation is still too high, so increase it again” ignores that latest inflation figures only reflect the impact of the cash rate at 3.85 per cent.

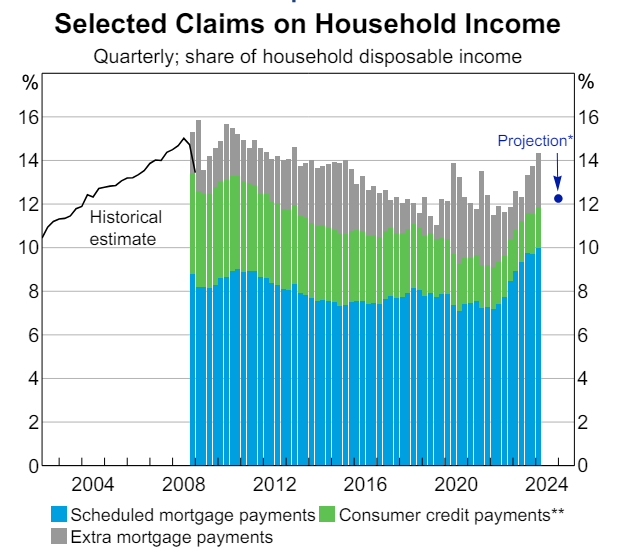

There’s a nice graph in the SoMP they should study closely.

There are still a bunch of fixed-rate mortgages about to roll off into higher variable rates this year.

The RBA graph shows the combination of scheduled mortgage and consumer credit payments will rise to take a bit more than 12 per cent of household disposable income by the end of the year.

But there’s a catch. Consumer credit is shrinking. The RBA believes – and it’s a safe forecast given it has the loan numbers – that mortgage repayments will rise from 10 to 10.5 per cent of household income.

That’s the equivalent of two RBA rate hikes.

And remember, fewer than 40 per cent of households have a mortgage, a smaller number again have mortgages big enough to be hard to handle while some fortunate souls are still able to make extra payments.

Those households that are being squeezed hard by present monetary policy are taking a vast amount of pain for the team.

It would be cruel – and unnecessary – to inflict more while monetary policy is yet to catch up with businesses padded out by poor Treasury policy and the last two hikes are yet to hit home, so to speak.