How bosses can use your wage like a credit card

Unpaid superannuation turns employees into "unwilling creditors". Photo: Getty

A disturbing number of small businesses use their employees’ superannuation entitlements like credit cards, an expert has warned.

Cath Bowtell, CEO of Industry Fund Services, said her company has strong evidence to suggest that a big contributor to Australia’s black hole of unpaid super is small businesses turning their workers into “unwilling creditors”.

“They often use it for cash flow. These businesses are effectively borrowing that money without the employee knowing – they’re an unwilling and unknowledgeable creditor,” Ms Bowtell told The New Daily.

IFS collects unpaid super on behalf of nine industry funds. In 2015-16, it contacted about 192,000 employers it believed to be behind on their super payments, which resulted in 37,400 of them coughing up $182 million owing to 297,000 workers. And this is “only the tip of the iceberg”, Ms Bowtell said.

The vast majority of these employers (about 29,000) paid up after just one reminder phone call. Most had fewer than 10 employees.

The second escalation, a solicitor’s letter, recouped $34 million from another 5500 employers. Little more than 400 cases were resolved in court.

Ms Bowtell said this relative ease of collection was because few overdue businesses were truly at risk of insolvency. They were simply borrowing from their workers to patch over a cash flow problem.

“The constant feedback from our credit collection officers who do the phone calls is that cash flow is one of the most common reasons the employer will give for not paying.”

‘Cash flow’ usually refers to how much money a business has on hand to pay its bills, such as new stock, debt repayments and lease.

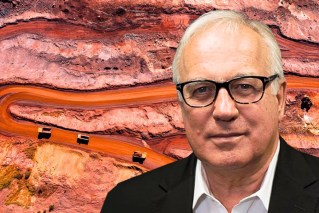

IFS chief executive Cath Bowtell says all it takes is a reminder phone call for most tardy employers to pay up.

The enormous problem of unpaid superannuation is estimated by Industry Super Australia to be in the realm of $5 billion a year, affecting more than two million workers.

Ms Bowtell said super funds are best placed to prevent it, as the Australian Taxation Office cannot see outstanding amounts until a year after the payments are due. “It can be five quarters from when the contribution was due that the ATO sees the file,” she said.

Employees themselves struggle to track payments, and have little power to enforce payment even if they do notice their super has gone unpaid, Ms Bowtell said.

But even though super funds can see straight away if a payment is due, they are constrained by legal ambiguity, she said.

Currently, no statute gives funds the right to chase unpaid super. In its absence, IFS operates under contract law. But this requires proof of a contractual relationship between the employer and the fund. Unless the fund is the ‘default’ for their industry, this can be difficult.

To remedy this, Parliament should empower the funds to collect super debts, she said.

“The funds are the ones with the most timely warning that a payment is overdue, so empowering them and giving some more clarity around their standing to take those proceedings would be a really helpful improvement to the system.”

A parliamentary committee is currently examining the issue of unpaid super and will report in April.