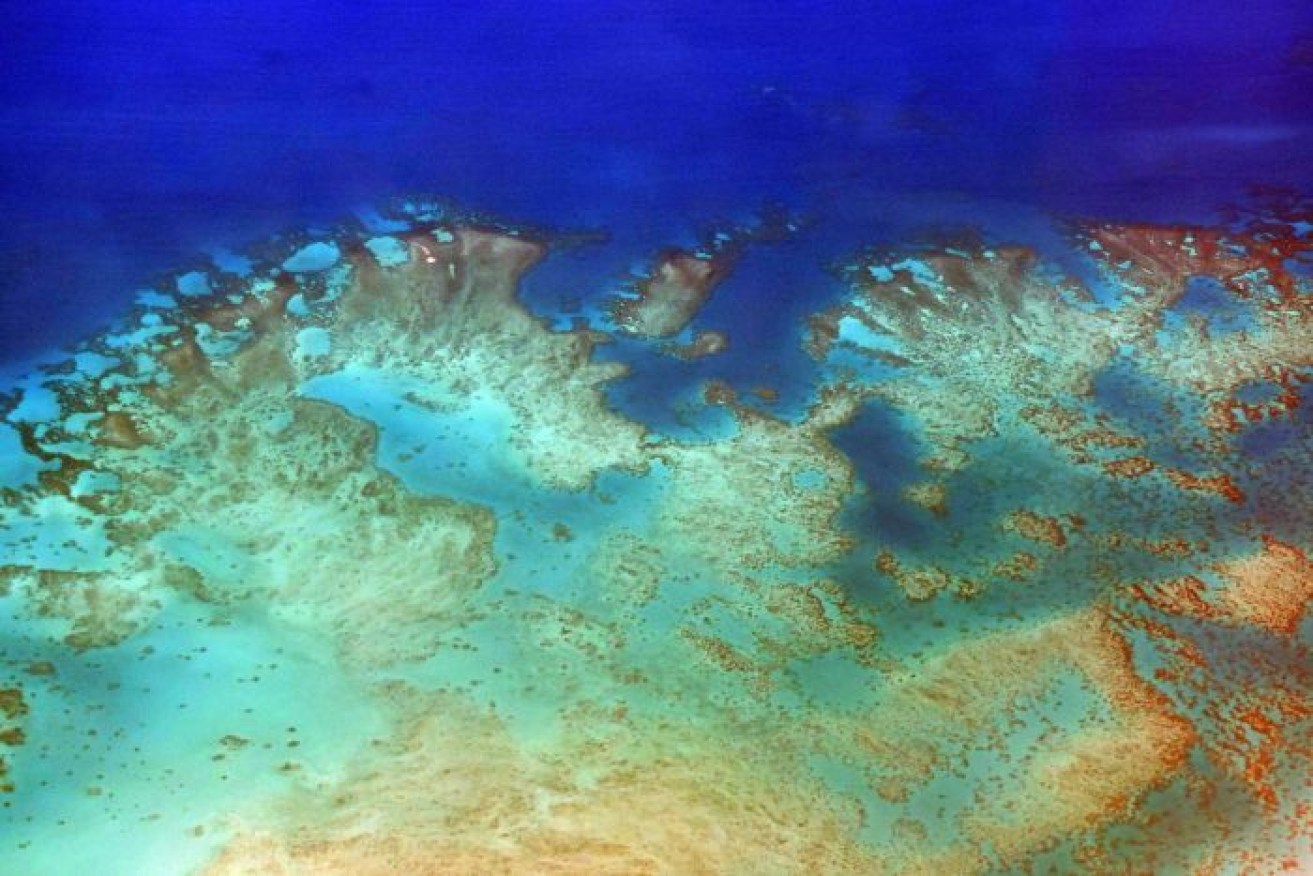

Great Barrier Reef coral bleaching causes numbers of baby coral to plummet

New coral births have been knocked down because adult corals were killed during the 2016-17 bleaching events. Photo: Getty

The amount of baby corals born on the Great Barrier Reef crashed in 2018 in what scientists are describing as the early stages of a “huge natural selection event unfolding”.

They found new coral “births” dropped by 89 per cent as a direct result of back-to-back bleaching events in 2016 and 2017.

And the types of corals that were able to reproduce changed too, meaning there will be long-term reorganisation of the reef ecosystem if the trend continues.

The reason there was such low birth or “recruitment” of new corals is because many of the mature breeding adults were wiped out in the bleaching events of the previous two years, and so weren’t around to produce offspring.

It will take the fastest-growing species a decade of bleaching-free conditions to recover their breeding populations, they report in the journal Nature today.

And some of the slower-growing coral species will need 20 years or more to recover.

But severe bleaching events, which used to occur once every 25 years prior to the 1980s, now occur on average every 5.9 years, meaning it is statistically likely that another event will hit before the reef has recovered from the last.

What we’re seeing today is likely the early stages of a change to a much flatter, less diverse and smaller reef, as many fragile species die out and are replaced by fewer, but more robust species according to lead researcher Terry Hughes from James Cook University.

“We’ve always anticipated that global warming would change the mix of species on the Barrier Reef, but we’re surprised by how quickly that’s now unfolding,” Professor Hughes said.

The middle and northern 1400 kilometres of reef showed the biggest declines in the most important reef-building corals, the ecologically dominant Acropora taxon, down to just 7.3 per cent of historical breeding levels.

The far southern end of the reef, which dodged bleaching in 2016 and 2017, actually showed a very slight increase in new coral recruitment in the 2018 spawning season.

But the researchers said they found “no evidence” that these southern reefs were helping to regenerate reefs in the north.

That’s because prevailing water currents travel in the opposite direction, said reef scientist Emma Kennedy from the University of Queensland, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Just like the East Australia Current in Finding Nemo, where the animals travel down the coast to Sydney, we know from genetic studies that the corals move from north to south,” Dr Kennedy said.

Which corals are surviving and why?

Spawning corals like Acropora have been hit the hardest by bleaching. Photo: AIMS/Roger Steene

Corals on the Great Barrier Reef reproduce in one of two ways.

About 90 per cent of reef-building corals breed by spawning, where coral sperm and eggs are “broadcast” out into the water column where fertilisation happens. The fertilised egg can float around for up to a few weeks, before swimming to the sea floor and “settling” at a site to grow.

Most of the big and really diverse corals reproduce in this way, including the fan and table corals that make the reef structure.

But the spawning corals are much more susceptible to bleaching, and so they got hammered much harder during the 2016/17 bleaching events.

Because of that, there were fewer living adult spawners around to reproduce in 2018.

The other 10 per cent of reef builders – which are usually the smaller, flatter corals, reproduce by brooding – where fertilisation happens internally, the fertilised egg is released into the water column, floats for about 12-24 hours, then settles to grow.

While there was far less coral born in 2018 overall, unlike in previous years, brooders outnumbered spawners.

The transition of the Barrier Reef to these smaller brooder corals is likely to happen faster as the climate continues to warm, according to Professor Hughes.

“We’re not saying there won’t be a reef in 10 years’ time, but we are saying it’s becoming a very different system.”

The IPCC forecasts a loss of about 90 per cent of reefs as warming hits 1.5 degrees, but Professor Hughes thought that was a bit pessimistic. Instead, he said, many reefs will persist, but they will simply be far less diverse.

What are the consequences?

Brooding corals are less capable of recolonising damaged reef. Photo: Supplied/Peter Mumby

A reef dominated by brooding corals will be more resilient to bleaching events, but will struggle to recover from crown-of-thorns starfish invasions, cyclones and other disturbances, according to Dr Kennedy.

While a cyclone may damage a path of reef up to 100-kilometres wide, new brooding corals from the undamaged fringes are limited in how far they can travel.

“It takes longer [to recover damaged reefs] because the brooding corals tend to spawn and settle closer to the adult colony than the spawners,” she said.

“The spawners can travel much further and reach much more degraded reef.”

Diversity of fish and other marine life is also likely to drop as the transition unfolds.

As the reef structure becomes less three-dimensional and complex, habitat and food sources are reduced.

Dr Kennedy likened reef structure to trees in a rainforest; if the trees become shrubs, the diversity of animals living in them is lost.

And that has flow-on effects for the wider food web.

Numbers of ocean-going fish and sharks, including many commercial seafood species, are likely to diminish as their food supply shrinks.

“It’s amazing how much you lose,” Dr Kennedy said.

Spawning events do fluctuate somewhat between years, but natural cycles don’t explain the “massive” crash of 2018, Dr Kennedy said.

If the reef is able to get an extended period without bleaching, it is possible it may still recover to its previous state.

But that’s looking less likely. Drastically reducing emissions to halt the advance of climate change is the only thing that may allow that to happen, according to Professor Hughes.

“It will be a different system, it will behave differently in terms of network links shortening, biodiversity is likely to be lower, coral cover is likely to be lower,” he said.

“But if we can reach 1.5 [degrees of warming] and not go beyond it, we’ll still have a functioning coral reef. It just won’t look like it did three years ago or 30 years ago.”

–ABC