The new building brick that could change the way we view waste

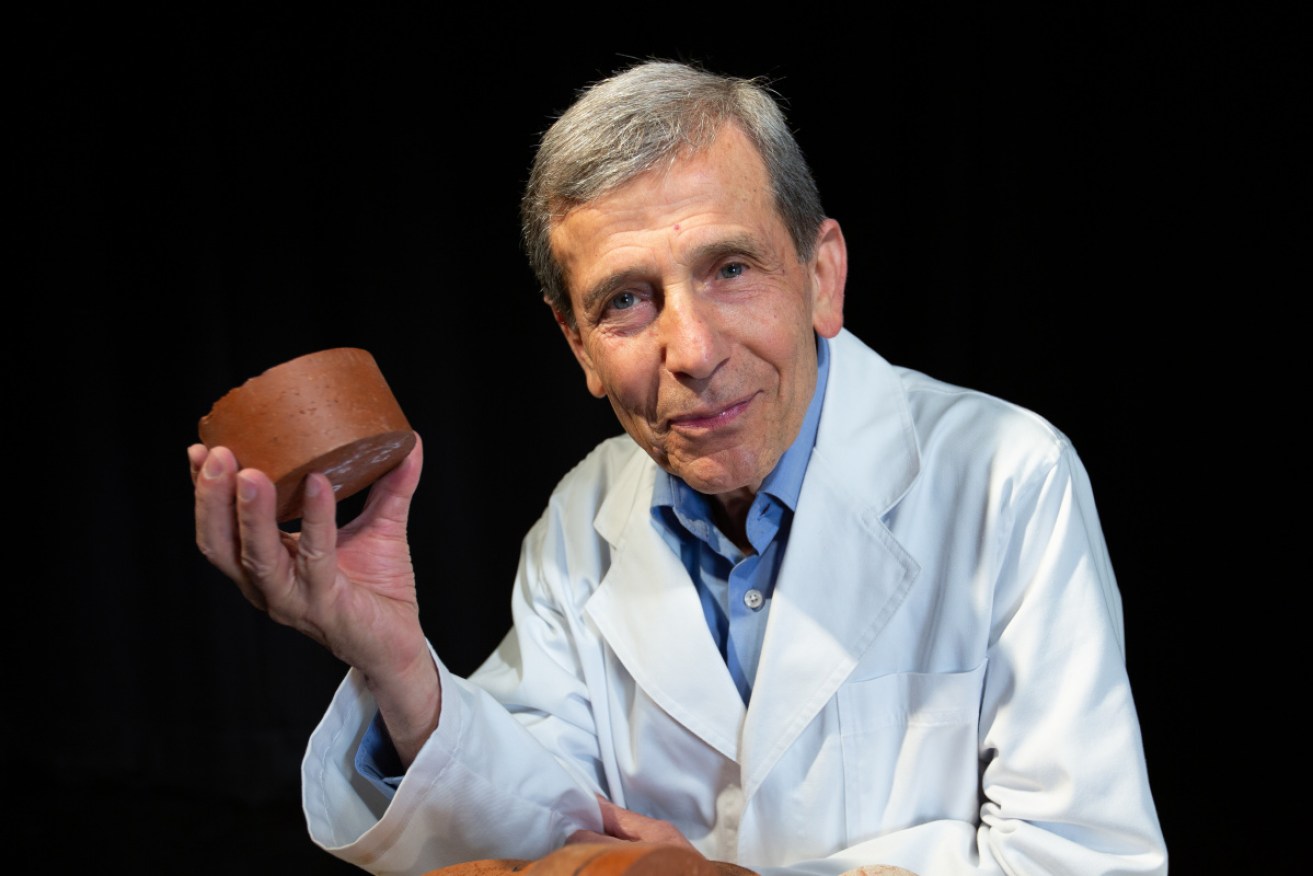

Associate Professor Abbas Mohajerani with a biosolids brick. Society can't afford to poo-poo the idea. Photo: RMIT University

Melbourne researchers have developed a house brick that uses up to 50 per cent less energy when being fired.

It’s also lighter than your everyday clinker, is very strong, takes heavy metals out of the environment, is more porous and so promotes heat insulation – and would make the construction industry more eco-friendly.

And it would significantly free up landfill.

The catch? It’s a psychological one in the public mind. The new brick, developed by RMIT University scientists, is made using biosolids, the sludgy remains of sewage after it goes through the wastewater treatment process.

Flush with success

In other words, what you drop into your toilet has the potential to build walls and make the world a more sustainable place.

Biosolids bricks could significantly reduce the world’s stockpile. Photo: RMIT University

The US produces about 7.1 million tonnes of biosolids a year, while the EU produces more than 9 million tonnes. In Australia, 327,000 tonnes of biosolids are produced annually.

While some biosolids are used in agriculture as fertiliser (in dry form it looks like soil) most of it ends up in landfill or storage.

This has proved unsustainable for Melbourne Water and its treatment plants. Last May the body announced it has trucked its millionth tonne of biosolids from its eastern treatment plant to a landfill rehabilitation project – but it said it had hopes that the construction industry might one day use biosolids in bricks and offer a permanent solution to the problem.

Those hopes have been nurtured for a long time. Melbourne Water trialled biosolid bricks 15 years ago in partnership with a South Australian brick company.

Biosolids put a strain on water treatment plants

The results were encouraging and the construction industry wasn’t turned off by the idea. But the bricks weren’t durable, and for Melbourne Water it was back to the drawing board.

Eventually Associate Professor Abbas Mohajerani, from RMIT’s school of engineering, took up the challenge.

Dr Mohajerani had previously experimented with making bricks and asphalt from cigarette butts.

“There are six trillion of them littering the world,” he said in an interview that suggested he regards cigarette butts as a personal affront, and hasn’t given up on the idea of making them useful.

He’s become similarly passionate about biosolids and how it can be used to conserve resources in the brick industry. “More than 3 billion cubic metres of clay soil is dug up each year for the global brickmaking industry, to produce about 1.5 trillion bricks,” he told The New Daily.

“I tried to visualise what that means… and worked out it is the equivalent of 1000 soccer fields turned into a hole 440 metres deep.”

With funding from RMIT, Melbourne Water and the Australian government Research Training Program, Dr Mohajerani became the lead investigator in producing a biosolid brick that has proved technically viable.

He said the research tested the physical, chemical and mechanical properties of fired-clay bricks incorporating different proportions of biosolids, from 10 to 25 per cent.

The biosolid-enhanced bricks passed compressive strength tests and analysis demonstrated heavy metals were largely trapped within the brick. Also, the biosolids bricks were more porous than standard bricks, giving them lower thermal conductivity – and would make households more environmentally sustainable.

They smell OK too

The research also showed brick-firing energy demand was cut by up to 48.6 per cent for bricks incorporating 25 per cent biosolids.

“This is because of the organic content of the biosolids and so could considerably reduce the carbon footprint of brick manufacturing companies,” Dr Mohajerani said.

But how soon could these bricks come on the market?

Dr Mohajerani said he hoped that government building codes could confidently mandate a conservative 15 per cent biosolids component in house bricks in the near future – based on the success of the research.

But without the political will, “It would take another 20 years” and the problems dogging water treatment plants would only be compounded.

A spokeswoman from Melbourne Water said there would be “further work and development around this exciting research”.