COVID-19 origin: ‘It looks like this virus was designed to infect humans’

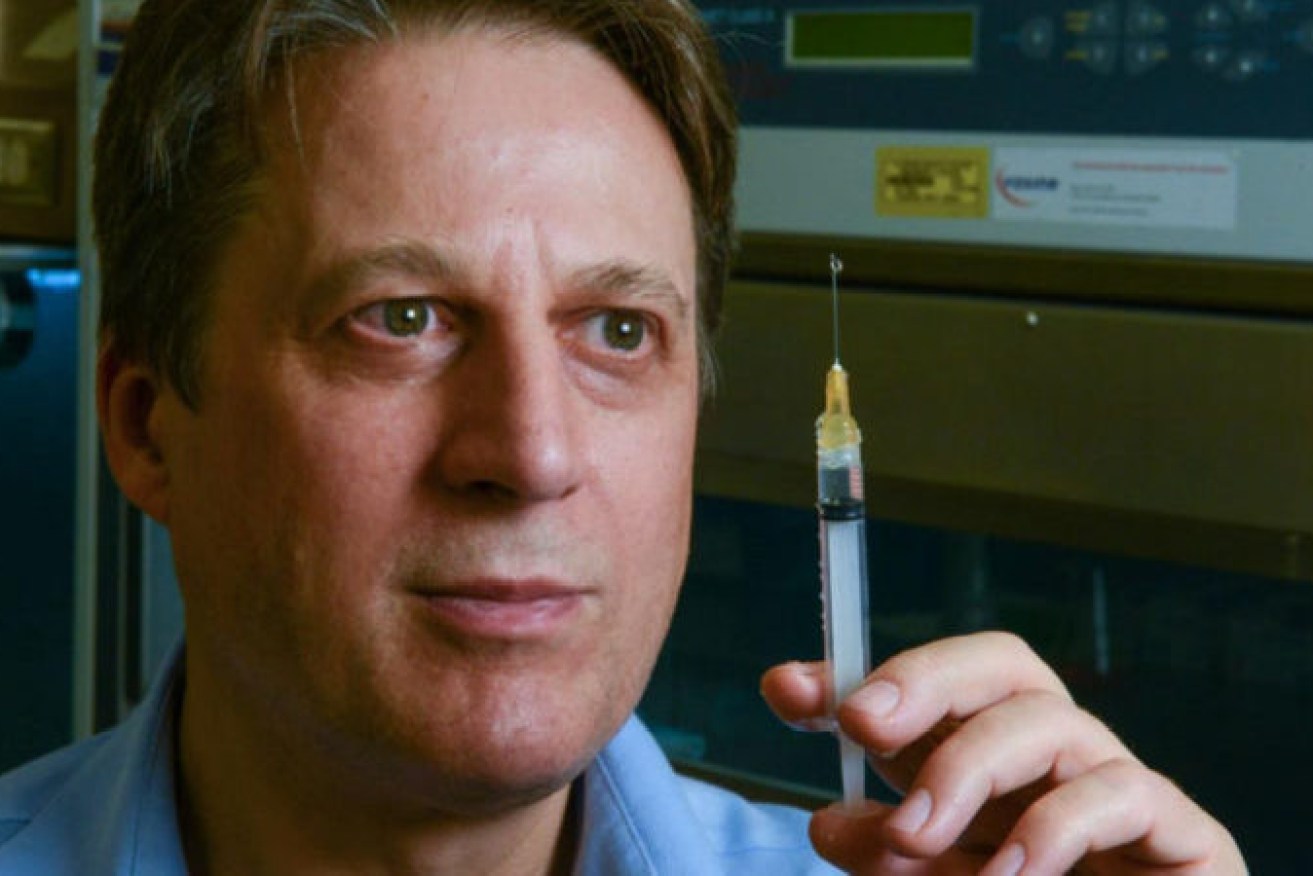

Professor Nikolai Petrovsky was shocked by his study's findings. Photo: Flinders University

In recent weeks, there has been a radical shift in sober thinking about where the SARS-CoV-2 virus, better known as COVID 19, originated.

Early talk about an accidental leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology – where bat coronaviruses are modified to become more infectious to humans – was largely written off as a conspiracy theory.

As The New Daily reported a month ago, the lab-leak theory is being investigated with vigour – under the direction of United States President Joe Biden – notwithstanding the limited access investigators have had to the Wuhan lab.

One of the compelling pieces of evidence being examined by members of the US Congress was done by Australian researchers – who were “shocked” by their own findings.

Their paper, published last week, found that the coronavirus is most ideally adapted to infect human cells – and not bat or pangolin cells, thought to be the likely origin culprits.

The study findings, from Flinders University and La Trobe University, also ruled out monkeys, snakes, cows, tigers, hamsters, cats, civets, horses, ferrets, mice, and dogs.

On the face of it, this stands as an intriguing challenge to the prevailing theory that SARS-CoV-2 virus originated in a bat and was then passed on to people via another, unidentified animals.

The problem is, the Australia data found that bats were a very poor fit for infection by the coronavirus, while humans “were way off the top of the list”.

These scientists were convinced of an animal origin

One of the co-authors of the study is Professor Nikolai Petrovsky. He is director of endocrinology at Flinders Medical Centre and a professor of Medicine at Flinders University. He’s also vice-president and secretary-general of the International Immunomics Society.

Professor Petrovsky said the research, which began last year when the pandemic was taking hold, was based on the assumption that “this was another natural transmission” rather than an engineered one.

“We were trying to find the particular species of animal in which this virus might have originated,” he told The New Daily.

The world is now full of armchair virologists who understand that the spike protein (S) of the coronavirus gains entry to a human cell by binding to the cell’s ACE2 receptor – “like a key being inserted into a lock” is the common metaphor.

Essentially, ACE2 acts as a cellular doorway – or receptor – for the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Professor Petrovsky – with La Trobe Professor David Winkler and others – used genomic data from the 12 animal species to “painstakingly build computer models of the key ACE2 protein receptors for each species”.

These models were then used “to calculate the strength of binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to each species’ ACE2 receptor”.

Surprisingly, the results showed that SARS-CoV-2 bound to ACE2 on human cells “more tightly than any of the tested animal species, including bats and pangolins”.

If one of the animal species tested was the origin, it would normally be expected to show the highest binding to the virus.

Said Professor Petrovsky, “What shocked us, and not what we were expecting, was that humans came out at the very top.”

What animal came in second?

The team’s modelling shows the SARS-CoV-2 virus “also bound relatively strongly to ACE2 from pangolins, a rare exotic ant-eater found in some parts of South-East Asia with occasional instances of use as food or traditional medicines”.

The pangolins had “the highest spike binding energy of all the animals the study looked at – significantly higher than bats, monkeys and snakes”.

Pangolins were an early suspect, because of a coronavirus it was carrying. But the pangolin coronavirus had less than 90 per cent genetic similarity to SARS-CoV-2.

“And hence could not be its ancestor,” Professor Petrovsky said.

However, the specific part of the pangolin coronavirus spike protein that binds ACE2 is “almost identical to that of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein”.

How to explain this incongruence? Maybe the pangolin and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins were of evolutionary cousins.

They may have evolved similarities “through a process of convergent evolution, genetic recombination between viruses, or through genetic engineering, with no current way to distinguish between these possibilities”.

In other words, it’s a possibility that the hand of man interfered with these viruses that were adapted pangolins and humans.

Or it could be the natural world doing its creative thing.

What does this mean?

Getting into a cell is one thing – but making an effective take-over of the cell is another issue. It usually happens via a series of infections, during which the virus adapts.

Ordinarily, then, the first human infection by a virus wouldn’t be a potent event.

What the researchers found in their modelling: it appears that human cells, from the beginning, were ripe for a takeover. They launched into the world, fully adapted to infect people.

This is hot stuff but, as Professor Petrovsky makes plain: “It’s just one piece of evidence that has to be assessed with all the other evidence.”

Has this happened before?

“You never say never,” said Professor Petrovsky.

“But what we know is this: If you look at SARS, that only became human-adapted through a complex series of events that have been mapped – starting with bats and then mutating, moving on to civets, and from civets to humans.”

The pangolin was suspected of passing the coronavirus to humans. Photo: Getty

Over three to four months of human infection, “the virus adapted and became more efficient” – as one would expect.

“The virus is usually weak when it infects a new species until it has time to adapt and become more efficient,” said Professor Petrovsky.

“But this virus was extremely good at infecting humans and there wasn’t a clear explanation for that. So it means there’s a coincidence or it could mean there had been some intervention that helped the virus become adapted to humans”.

Which is why scientists are looking at the Wuhan Institute of Virology: it houses more bat coronaviruses than anywhere else in the world, and some of the work done there involves re-engineering coronaviruses so they adapt to infecting humans more easily.

“Which is another remarkable coincidence – or it’s telling you something,” said Professor Petrovsky.

“Looking just at the data you’d say that it looked like this virus was designed to infect humans,” he said,

“But of course, scientifically, you have to go back and ask how could this have happened without infecting a human before?”

It is a big question and “it’s currently an unanswered question”.