‘Citizen science’: DIY vaccine’s developers are their own COVID guinea pigs

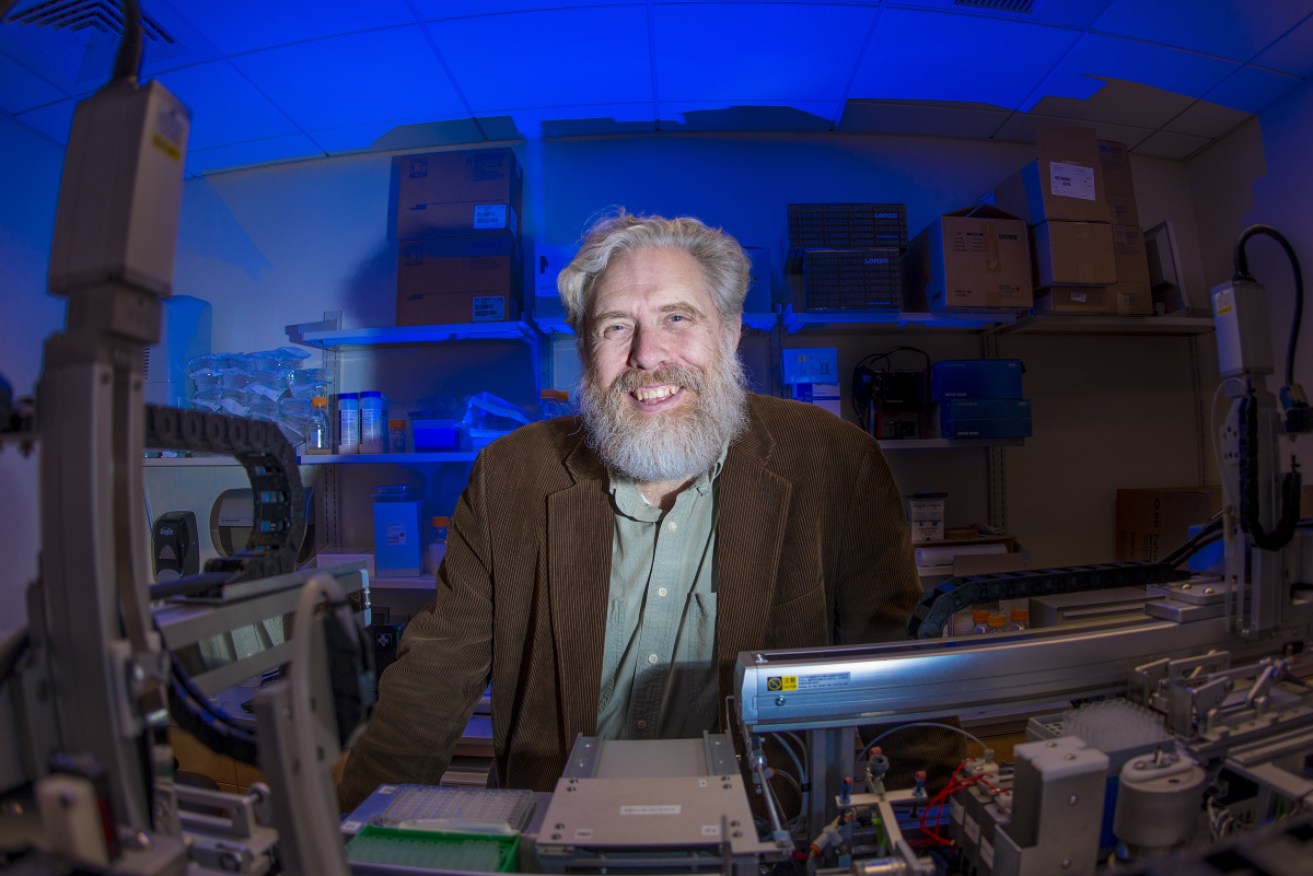

Professor George Church, famed Harvard geneticist, is one of the scientists to have made and snorted the DIY vaccine. Photo: Getty

The world is desperate for a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine, and a group of ‘citizen scientists’ is taking matters into their own hands, publishing a DIY version online.

The recipe is pretty straightforward: five mail-order ingredients that you mix together and squirt up your nose. Two of those ingredients are table salt and deionised water.

Does it work? Too early to tell. Is it safe? Not sure yet.

But a detailed white paper – a set of recipe instructions – is available online. It includes a hefty set of disclaimers as to the vaccine’s safety and efficacy.

Nutty on the face of it, the vaccine has been snorted by up to 70 US scientists and science “enthusiasts”, including the famed George Church, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and director of the Personal Genome Project.

Professor George Church snorting the experimental vaccine. Photo: George Church

You probably know him best as the guy working on bringing an elephant-woolly mammoth hybrid back from the dead.

Professor Church reportedly took two doses a week apart in early July.

“The doses were dropped in his mailbox and he mixed the ingredients himself,” according to a report in MIT Technology News.

Why take such a risk?

In the report, Professor Church said that he believed the vaccine was “extremely safe” – and that he was more concerned that people were “highly underestimating” COVID-19. He said that he hadn’t left his home for five months

Dr Preston Estep designed the vaccine to be made from mail-order ingredients. Photo: Alex Hoekstra

“I think we are at much bigger risk from COVID, considering how many ways you can get it, and how highly variable the consequences are,” he said.

The vaccine was designed by Dr Preston Estep, a former doctoral student and “protege” of Church’s.

On his LinkedIn page Dr Estep is described as Chief Scientist at Rapid Deployment Vaccine Collaborative – also known as Radvac – “a non-profit that launched in March 2020 in response to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.”

Radvac’s mission is “rapid development, testing, and public sharing of vaccine recipes that are simple enough to be produced and administered by citizen scientists.”

As it stands, Radvac is a loose group of Dr Estep’s friends and colleagues – mostly Harvard and MIT alumni – who have taken the vaccine or have the ingredients in their possession.

So is this legal or what?

Ordinarily, any kind of drug or vaccine trial requires approval by the US Food and Drug Administration and governance by an ethics committee.

Dr Estep told MIT Technology News that the group has obtained legal advice. He is apparently confident that the Radvac vaccine doesn’t sit under the FDA’s purview because the vaccine is self-administered, each user mixes the ingredients themselves – which requires some scientific training – and because no money has changed hands.

The white paper makes clear that users must be over 18 and assume all responsibility.

One of Radvac’s Hardvard-trained founders, Don Wang, A clogged nostril seems to be the main side effect experienced so far. Photo: Alex Hoekstra

The many warnings in the ‘terms and conditions’ include: “Use of this vaccine may change the efficacy of any future vaccines you may take

or that are administered to you, in unknown ways.”

So far the FDA hasn’t intervened – or apparently responded to media enquiries. Although the project has been in train for nearly five months, it was only in the last couple of days that Dr Estep went public.

Professor George Church told MIT Technology Review:

“What the FDA really wants to crack down on is anything big, which makes claims, or makes money. And this is none of those,” says Professor Church.

“As soon as we do any of those things, they would justifiably crack down. Also, things that get attention. But we haven’t had any so far.”

Does the vaccine have legs, even theoretically?

According to MIT Technology Review, the Radvac vaccine is what’s called a “subunit” vaccine because it consists of fragments of the pathogen. In this case, the vaccine uses commercially available synthetic peptides as small portions of viral sequences that match up with parts of the virus. These have no disease-making potential.

There are other subunit vaccines under mainstream development against the coronavirus, including a US $1.6 billion project funded by the US government.

The Radvac vaccine also uses chitosan, a sugar obtained from the exoskeleton of shellfish. It’s used in medicines to treat obesity, high cholesterol and high blood pressure. The Radvac vaccine uses chitosan as a protective coating that allows the peptides to pass the mucous membrane.

Another ingredient is sodium triphosphates, a preservative for seafood, meats, poultry, and animal feeds. It’s used for water retention.

Mixed up with table salt and water, and syringed into the nose, the vaccine may prompt immune cells to develop in the tissues of the nose and throat.

As the MIT Technology News observes: “Such local immunity may be an important defense against SARS-CoV-2.”

Has that happened? Professor Church has opened his laboratory to the project to test whether or not an immune response has been generated by the vaccine. Dr Estep says that the results so far are “complicated” and not ready to be made public.

The New Daily has decided not to link to the Radvac White Paper. The researchers have made plain that their vaccine is designed to “add a layer of protection” against COVID-19, and urges potential citizen scientists to maintain social distancing, the wearing of masks and other basic precautions against COVID-19.

The New Daily has invited Radvac to make a guest appearance on our new podcast: What does that mean?

Click here to listen to the first episode of What does that mean? with host John Elder.