Why phones of the future might sweat, just like us

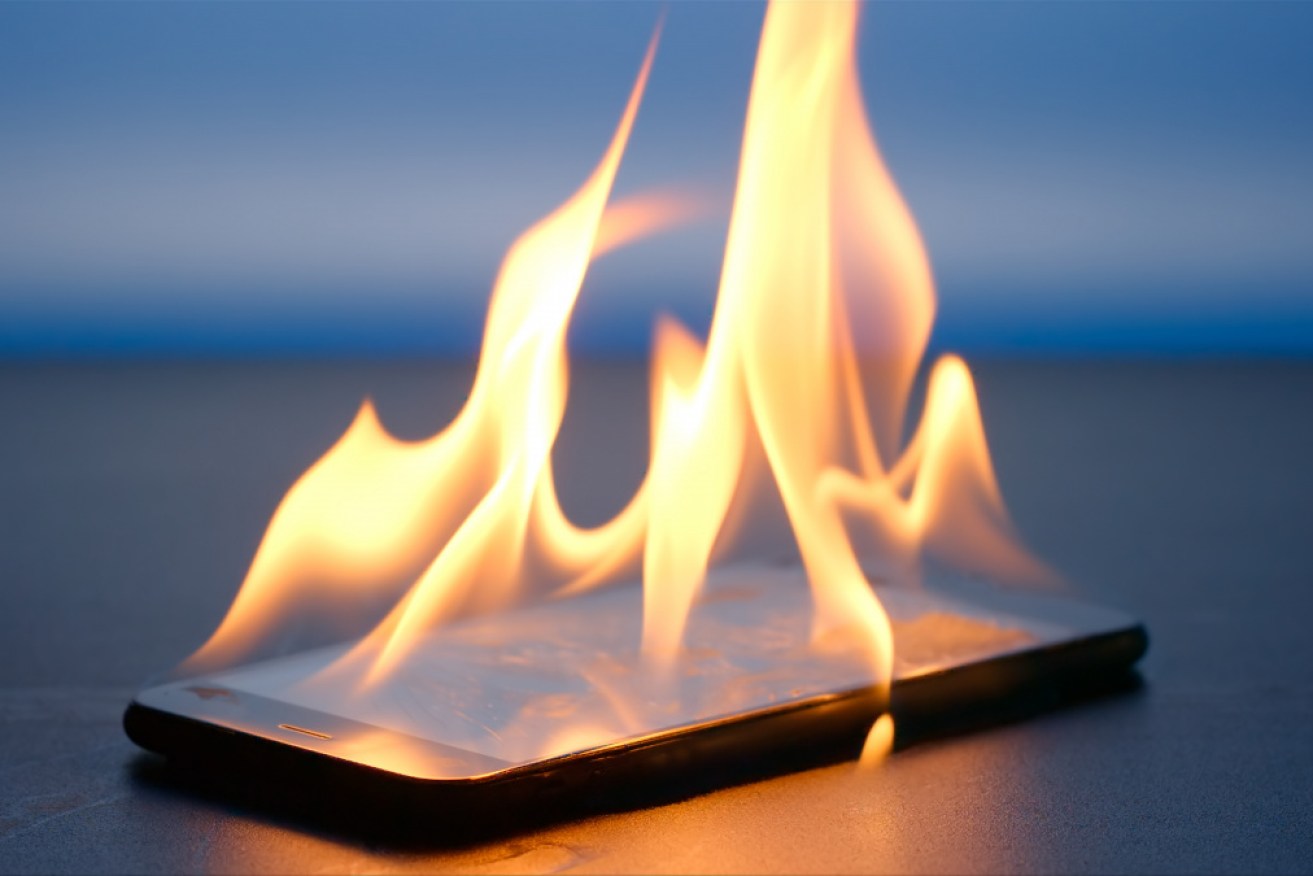

There's burner phones and then there's burning phones. A team of Chinese scientists may have developed a peculiar way of remedying the latter. Photo: Getty

As phone manufacturers integrate more and more capabilities into their devices, they’re hamstrung by one particular limitation: Heat.

As a general rule, a higher-end smartphone released today has about the same, if not better, processing power than a PC or laptop of five years ago.

The result? All those busy chips and processors, combined with hot temperatures, and we get a “too hot to operate” message.

If we’re super unlucky, we’ll cook our phone from the inside.

While high-powered computers are kept cool by in-built fans, users probably wouldn’t be too happy with carrying around a smartphone with a clip-on oscillating fan in their pockets – it’s just not practical.

Instead, scientists out of Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China are looking to copy mammals as a way of keeping core temperatures down.

They’ve designed a coating that will emulate the way a mammal sweats in hot weather as a method to cool the device’s core temperature.

The research was published on January 22 in the journal Joule.

Instead of fans (like in computers) or materials like waxes and fatty acids (which are common at present), this technique involves a coating that releases water vapour to get rid of excess heat from operating devices.

Senior author Ruzhu Wang studies refrigeration engineering at the university, and explained the technique, which uses metal organic frameworks cooled at 10 times the rate of the current common process.

Smartphones can go into shutdown mode if they get too hot – typically over 35 degrees. Photo: Apple

These frameworks mimic a mammal’s sweat function by absorbing moisture from the air, and releasing vapour when it’s heated up.

In the past, the frameworks have been trialled to try and draw water from desert air. But because they’re expensive, they’re not suited to large-scale projects.

“Our study shows electronics cooling is a good real-life application of (these frameworks),” Professor Wang said in a media release.

“We used less than 0.3 grams of material in our experiment, and the cooling effect it produced was significant.

“The development of microelectronics puts great demands on efficient thermal management techniques, because all the components are tightly packed and chips can get really hot.

“For example, without an effective cooling system, our phones could have a system breakdown and burn our hands if we run them for a long time or load a big application.”

They tested one particular coating on a microcomputing device (a simulated smartphone) and found it reduced the core chip temperature of the device by 7 degrees, when it was operating under a heavy workload for 15 minutes.

“In addition to effective cooling, (this coating) can quickly recover by absorbing moisture again once the heat source is removed, just like how mammals rehydrate and [get] ready to sweat again,” Professor Wang said.

“So, this method is really suitable for devices that aren’t running all the time, like phones, charging batteries and telecommunications base stations, which can get overloaded sometimes.”

But don’t expect to be seeing self-sweating phones for sale any time soon – the team say it will take some time to figure out how to get the expense of such technology lowered enough to roll out into the market.