Newly discovered river of stars fills most of the southern night sky

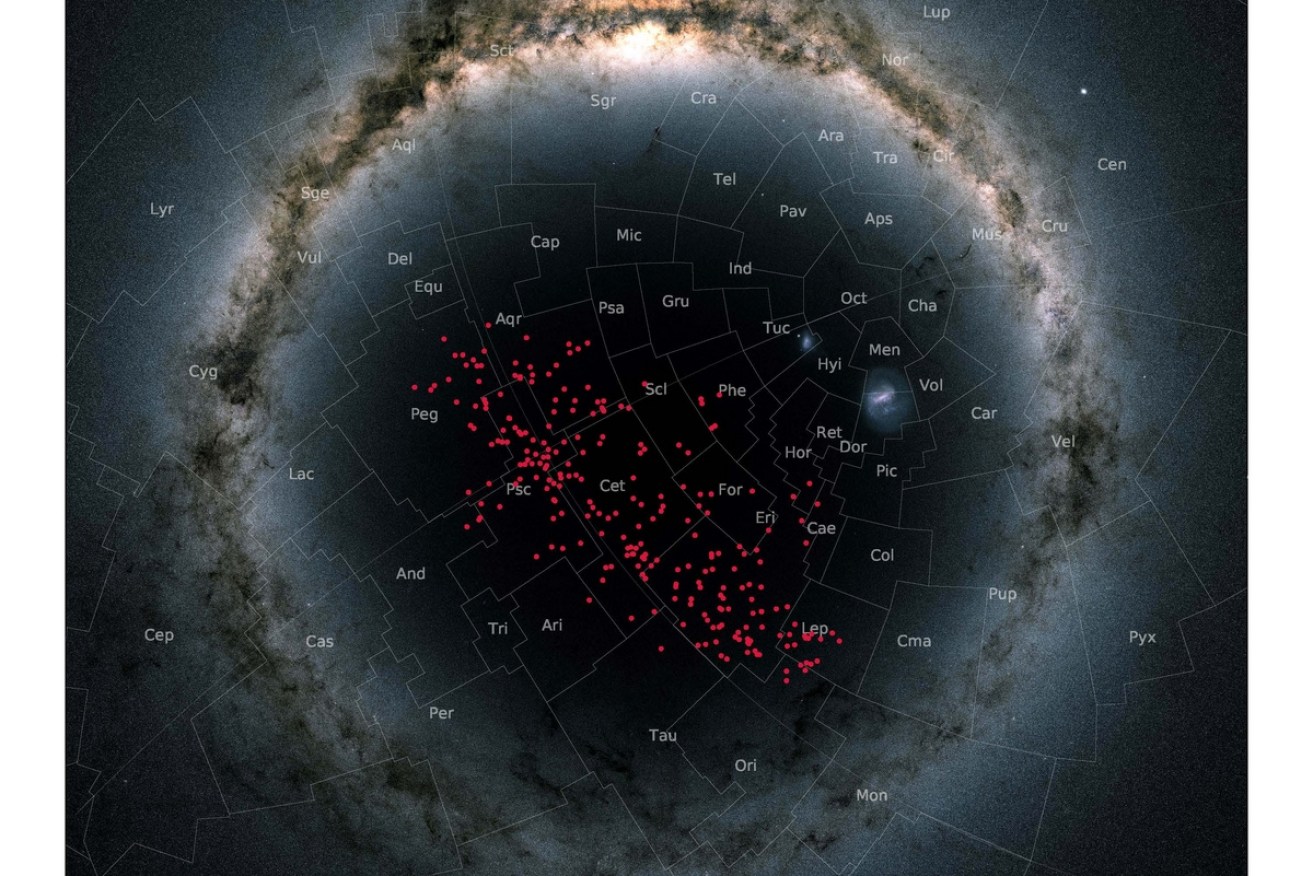

In this special projection, the Milky Way curves around the entire image in an arc. The stars in the stream are displayed in red and cover almost the entire southern Galactic hemisphere, thereby crossing many well-known constellations. Background image: Gaia DR2 skymap

A billion years ago, a star nursery gave birth to about 4000 stars. Ordinarily, this cluster of newborns would have been pulled apart by the galaxy’s gravitational forces and sent scattering through the Milky Way.

Instead, they generated enough gravity between them to hold together – and form a stellar stream, or a river of stars.

What’s relevant to Australia — and people living elsewhere in the Southern Hemisphere – is this river covers most of the southern night sky, flowing together as one mighty body.

Right under our noses

And while it has been streaming under the Earth’s gaze from long before people existed – and is relatively near to our solar system — until a couple of weeks ago, we didn’t know what we were staring at.

Researchers from the University of Vienna used data from the European Space Agency satellite Gaia to make their discovery, which they describe as being “shockingly close to the Sun” at 100 parsecs or 326 light years.

A glowing star nursery like this one birthed 4000 stars that travel together as a stream. Photo: NASA/JPL

The stream itself is four times as long – it would take 1304 light years to travel from one end to the other. So it’s huge.

João Alves is a professor of stellar astrophysics at the University of Vienna, and co-author of the research paper containing the astronomers’ findings published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

In a prepared statement from the journal, he said: “Identifying nearby disk streams is like looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack.

“Astronomers have been looking at, and through, this new stream for a long time, as it covers most of the night sky, but only now realise it is there, and it is huge, and shockingly close to the Sun.”

An astronomer’s dream

Dr Alves said finding such a stream “close to home is very useful, it means they are not too faint nor too blurred for further detailed exploration, as astronomers dream”.

The scientists used Gaia data to measure the 3D motion of stars in space.

As they surveyed the distribution of nearby stars moving together, they were drawn to a particular group that was unknown and unstudied – and that “showed precisely the expected characteristics of a cluster of stars born together but being pulled apart” by the gravitational field of the Milky Way.

“Most star clusters in the Galactic disk disperse rapidly after their birth as they do not contain enough stars to create a deep gravitational potential well, or in other words, they do not have enough glue to keep them together,” said Stefan Meingast, lead author of the paper, in a prepared statement.

“Even in the immediate solar neighbourhood there are, however, a few clusters with sufficient stellar mass to remain bound for several hundred million years. So in principle similar, large, stream-like remnants of clusters or associations should also be part of the Milky Way disk.”

Bigger than most known star clusters

In other words, the behaviour of the Milky Way predicted the existence of the stellar stream that is “more massive than most known clusters in the immediate solar neighbourhood”.

At one billion years old, the cluster has completed four full orbits around the Galaxy, time enough to be strung out into the stream-like structure as a consequence of gravitational interaction with the Milky Way disc.

According to Astronomy & Astrophysics, the river of stars can be used as a valuable gravity probe to measure the mass of the Galaxy. It also opens a path to telling us how galaxies get their stars, test the gravitational field of the Milky Way, and, because of its proximity, become “a wonderful target for planet-finding missions”.

Associate Professor Daniel Zucker is an an astronomer and researcher with Macquarie University. He is part of an Australian-led group of astronomers working with European collaborators on a project called the GALAH survey, which has decoded the “DNA” of more than 340,000 stars in the Milky Way, which they hope will help them find the siblings of the Sun – the stars that were born in the same cosmic nursery.

Dr Zucker said the discovery of the stellar stream being so close to our solar system – and containing heavy elements that are comparable to those in our Sun – could help solve the puzzle.

“We think stars form in clusters and over time they dissipate through the Milky Way,” he said.

“The stars in the (newly discovered stellar stream) are relatively young. They could be younger than a billion years … They could tell us how our Sun formed but also what happened to our Sun’s siblings. Like where are they now?”