Apple’s victory over banks could be a big win for consumers

The dispute boils down to lucrative card transaction fees. Photo: AAP

Three major banks have been forbidden by the competition regulator from using their collective might to challenge Apple Pay, a move the regulator warned could’ve hurt consumers by stifling popular technologies like tap-and-go while also making it even harder for Australians to switch banks.

Customers at the Commonwealth Bank, Westpac and NAB, as well as the smaller Bendigo and Adelaide banks, have been forced to wait months to access Apple Pay, the iPhone’s digital wallet app, because those banks have insisted on fighting Apple to protect their shares of millions of dollars in fees.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) issued a final determination on Friday denying banks the power to collectively negotiate with Apple for access to the iPhone’s near-field communication (NFC) antenna.

ANZ is unaffected by the ruling as it agreed in April last year to accept Apple Pay — a move it claims has attracted a flood of new customers.

American Express and dozens of credit unions have also struck deals for access to the iPhone app, which works with both debit and credit cards.

But the thousands of Australians who don’t have an Amex, ANZ or eligible credit union card will be forced to wait, perhaps indefinitely, to use their iPhones to make payments, as the holdout banks now say they’ll negotiate individually with Apple.

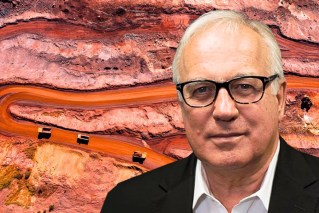

“While the ACCC accepts that the opportunity for the banks to collectively negotiate and boycott would place them in a better bargaining position with Apple, the benefits would be outweighed by detriments,” chairman Rod Sims said in a statement.

Millions of dollars in credit and debit card transaction fees hang in the balance. By allowing no other smartphone app except Apple Pay to access the iPhone’s NFC antenna, which ‘pings’ with card machines, Apple can exact larger fees.

According to US reports, Apple demands 0.15 per cent of every credit card transaction processed through Apple Pay. This is a huge threat to bank revenue, given that the Reserve Bank of Australia will from July 1 impose a cap on interchange fees.

Consumers dodge the ‘lock in effect’

Granting the banking bloc’s application could have made it even harder for consumers to switch between the banks, a risk the ACCC chairman dubbed the “lock-in effect”.

This is because Apple Pay is a “multi-issuer”, which means it can accept cards from any financial institution with which it has a pre-existing deal – unlike bank apps, which only accept their own cards.

“Apple Wallet and other multi-issuer digital wallets could increase competition between the banks by making it easier for consumers to switch between card providers and limiting any ‘lock-in’ effect bank digital wallets may cause,” Mr Sims said.

What the banks are fighting for is the ability to connect their smartphone apps to the iPhone’s NFC chip. Currently, only Apple Pay is allowed to connect.

If the banks had been allowed to use collective bargaining to gain access to the antenna, then each bank would’ve been able to protect the customer bases — and fees — they’ve built around those apps and card payments.

However, collective bargaining could have reduced “the competitive tension between the banks in the supply of payment cards,” Mr Sims said.

It could have also killed off popular innovations like tap-and-go, smartwatches, fitness wearable devices and other technologies “in their infancy”, he said.

‘Apple just wants your money’

The banking coalition argued the case had “always been about consumer choice” and that the denial would stifle competition and mobile wallet innovation.

“Apple has a stated desire to own the entire mobile wallet, and will use the beachhead into mobile wallets afforded to them by complete control over mobile payments on iPhone to exert control over the rest of the digital wallet,” the banks said in a joint statement.

The banks said they would now review their strategies separately.

The ACCC had already denied the banks an interim authorisation to jointly negotiate with Apple in August 2016. In November, it published a draft determination that foreshadowed Friday’s verdict.

Apple has not commented publicly on its victory.