Stung by drip pricing? Why this loathed business practice might be here to stay

QR codes at restaurants, cafes and bars are a newer example of drip pricing. Photo: Getty

Sick of hidden fees that only emerge and jack up what you thought was the final bill when you hit the checkout?

You’re not alone. The practice, loathed by many shoppers and loved by certain businesses, is known as drip pricing.

As Australian shoppers continue to grapple with it, there is some hope for consumers in Britain.

The country’s Department of Trade is consulting with industry and the public on drip pricing, and has also released research into the practice.

It found that “drip pricing is common across online providers”, with 46 per cent of online and mobile app providers including at least one drip fee.

Event and cinema tickets and gym memberships were the most likely transactions where consumers might face such fees. They also commonly used by airlines.

The British government has pledged “new powers to enable growing consumer harms to be tackled”.

But the proposal hasn’t gone down well with some businesses – with the airline industry saying any crackdown is likely to send airfares soaring.

One senior aviation figure told Britain’s Independent newspaper that buying a flight was “no different from buying a pizza – if you want extra toppings, you pay for them”.

A spokesperson for Airlines UK, which represents the major carriers in British aviation, said: “Unbundling products and offering greater choice that consumers demand is an important way that airlines compete and is well understood to have enabled air travel to become accessible for all.

“Any moves to reverse this are clearly not in the interest of UK consumers,” they said.

Back in Australia, ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods senior research fellow Ralf Steinhauser said drip pricing was often a “nagging small problem”, but it remained a persistent one.

“It’s usually within the $1 to $2.50 range, or in per cent something like 2-3 per cent of the total cost,” he said.

“We often just shrug it off, but it’s certainly there.”

Steinhauser said consumers often weren’t stung with the extra costs until they reached the checkout, and might feel obliged to complete their transaction.

“People aren’t going to walk away because of a $2 or $3 fee, even if it surprises us at the end of the checkout procedure,” he said.

“It is a time resource we are putting in and we’re reluctant to redo this, step back or go to the counter and make a payment.”

Australian experience

As in Britain, most Australians face drip pricing when they buy concert tickets, when fees appear part of the way through the transaction or at the checkout.

Another example is when cleaning fees add a surprise loading to the cost of a holiday rental.

One recent change for consumers, highlighted by Steinhauser, is bars, cafes and restaurants hiding checkout fees for patrons who use QR code menus.

“When you purchased food at the table with the QR code, there was a 2.5 per cent add-on fee that you could not waive,” he said.

“It happened to me and in the end, the checkout didn’t end up working, and when I went to the bar and ordered the same thing it was without the extra fee.”

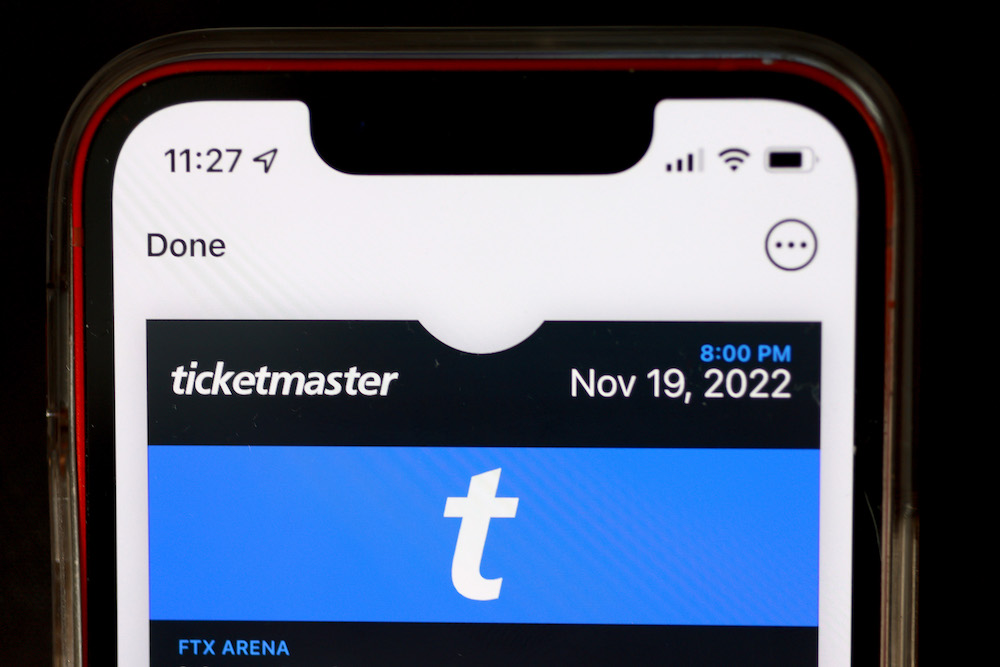

Many Australians face drip pricing when they buy concert tickets. Photo: Getty

He said there was no point in bringing it up with staff, who wouldn’t have been able to make any change.

“In this particular case, if I’d given feedback to the person at the counter where I ended up doing my order that there is this unfair fee, what are they going to do about it?”

“It’s a drip price. You only see it at the end.”

Enforcement

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission can investigate companies that sell products where the final price does not match the advertised price if reported, and has done so in the past.

The consumer watchdog defines drip pricing as when “a price is advertised at the beginning of an online purchase, but then extra fees and charges (such as booking and service fees) are gradually added during the purchase process”.

In 2017, the ACCC fined two Virgin Australia and Jetstar a collective $745,000 after they were deemed to have fudged the true prices of airfares.

Steinhauser said the ACCC had the tools to clamp down on the practice, but it required active enforcement.

“Other new forms may appear that may need the ACCC to look into this again,” he said.

“The ACCC has the ability to regulate those things, under the terminology of what is unfair or misleading price display.”