For most workers, inflation is worse than ABS data indicates

The battle against inflation is being waged in a very one-sided manner. Photo: Getty

Every consumer knows inflation is making it much harder to pay their bills.

Australia’s annual inflation rate peaked at 7.8 per cent at the end of 2022, and has since slowed down to 4.1 per cent as of December 2023 (most recent data).

But the increase in costs faced by most households has actually been much worse than these official inflation statistics suggest.

Australia’s statistical agency excludes mortgage interest costs from its Consumer Price Index (the main measure of inflation).

Its measure of housing costs (which accounts for one-quarter of the total consumer ‘basket’ measured by the CPI) includes the cost of purchasing newly constructed dwellings, actual rents paid to landlords by renters, and out-of-pocket household expenses like utilities.

There is no impact in the CPI arising from changes in housing ownership costs for owner-occupiers of previously built homes.

As a result of this curious methodology, the rapid hikes in interest rates imposed by the Reserve Bank of Australia over the last two years are not directly reflected in the CPI.

The ABS publishes alternative measures of the cost of living, called ‘Selected Cost of Living Indexes’. Unlike the CPI, these measures do include the cost of mortgage interest for homeowners.

Cost-of-living indexes are calculated separately for different types of households.

The category called ‘Employees’ includes the largest proportion of home owners with mortgages – and hence that category has seen the fastest increase in its cost of living as a result of rising interest rates.

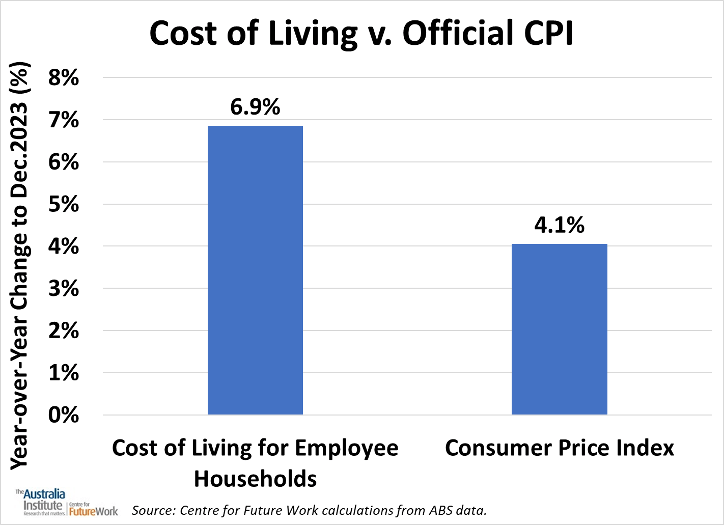

In the year ending in the December quarter of 2023, the cost of living for employee households (including mortgage costs) grew 6.9 per cent. That was almost three-quarters faster than the official CPI inflation rate (4.1 per cent).

So for workers, the pain caused both by inflation, and by the RBA’s one-sided response to inflation, has been far worse than traditional data suggests.

Source: Calculations from ABS Consumer Price Index, Australia, and Selected Living Cost Indexes, Australia.

It is painfully ironic that by relying solely on high interest rates to fight inflation (rather than considering other measures, such as price regulation, excess profit taxes, and supply-chain improvements), the RBA has actually made the cost of living crisis worse – especially for workers.

Official inflation statistics disguise this impact in Australia, but that doesn’t make it any less painful. In other countries, statistical agencies do capture the effect of higher mortgage costs on consumer price inflation – either directly (for example, in Canada) or indirectly (in the US they are captured via a category called ‘Owner Equivalent Rent’).

Households with less mortgage debt have experienced somewhat slower increases in their total cost of living than the 6.9 per cent increase affecting employees.

Self-funded retirees (generally with higher incomes and wealth, and hence least likely to have outstanding mortgages) had the slowest growth in cost of living last year: 4.0 per cent, about the same as CPI inflation.

But every other type of household (including age and super pensioners, and other government transfer recipients) experienced significantly faster increases in their cost of living than implied by the CPI.

The battle against inflation is being waged in a very one-sided manner.

Instead of recognising (and preventing) the impact of factors like excess profits, supply chain disruptions, and housing shortages on inflation, the RBA assumes inflation is caused only by ‘excess demand’. In other words, Australians have too much money to spend.

The RBA tries to siphon away that spending power through high interest rates, but this makes the cost of living even worse – more so for workers, than any other segment of society.

The RBA’s actions have actually increased the true inflation facing working households. But this impact is hidden in official CPI statistics. At a minimum, the RBA should at least be honest about the effect its policies are having on the true cost of living for Australians.

Jim Stanford is economist and director of the Centre for Future Work.

For more information on how the ABS measures housing inflation, and the differences between the CPI and the Cost of Living Indexes, see their information bulletin.