Michael Pascoe: Yes, RBA rate decisions are third-rate – but that’s by design

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has shifted the focus onto the RBA’s economic impact rather than the government, Michael Pascoe writes. Photo: TND/Getty

It was a remarkable Reserve Bank board meeting this month, but not because of anything to do with monetary policy – that remained the inequitable, conflicted, costly, third-rate mongrel of a thing it’s always been.

The remarkable bit was at the top of the published minutes where it was recorded that five of the eight members present were women while the gender split of the “others present” was five-five.

Two of the men were the secretary and deputy secretary, taking the minutes and keeping the board organised, so you could claim in terms of input and decision making, women outnumbered men 10 to six at the top of the country’s second most powerful institution – if you allow that the federal government is the most powerful.

And it is. By a long shot.

Despite the totally disproportionate reporting (yes, including this) of the RBA’s toing and froing and the pain it can inflict and the bubbles it can help inflate, it is a severely limited institution being made more limited by Treasury’s review, which simultaneously is setting up the bank to attract more attention with more media opportunities and bigger public profiles of RBA operatives.

Good heavens, among those now present for the board meeting is a chief communications officer.

The contradiction here is that Jim Chalmers’ quite pedestrian review rearranging the Martin Place furniture contained one sharp bit: Tightening the RBA’s focus on getting inflation down to 2.5 per cent, not just between 2 and 3 per cent. And that’s to be done purely by bashing people with interest rates.

“Forward guidance” – the thing that landed Philip Lowe in so much trouble – is out of fashion, as is other “unconventional monetary policy” such as quantitative easing after it proved to be a very expensive trick of marginal benefit.

As has been stated plenty of times before, it absolutely suits the government to have as much attention as possible focused on the RBA’s economic impact rather than on its own.

Playing along with the ruse that the RBA is responsible for inflation takes the pressure off the government to use its much more powerful fiscal policy to guide the economy.

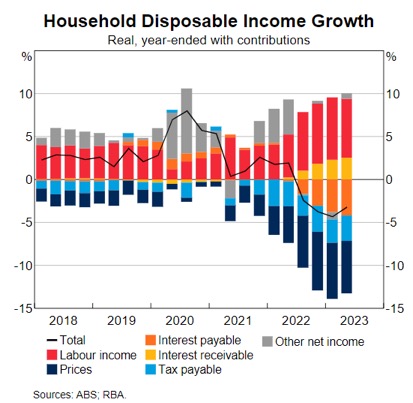

A quick illustration of what a cack-handed beast monetary policy is:

This graph from a speech by Dr Chris Kent in October on how monetary policy works shows in orange how “interest payable” sucked money out of households as the RBA increased rates – constricting consumption and reducing living standards on its way to increasing unemployment.

But the yellow bits above the line show how the RBA lifting rates obviously also increased “interest receivable” – households with savings enjoying income growth, enabling more consumption and improving their living standards.

By my rough reckoning of the proportions, that looks like 12 steps forwards in reducing household income and seven steps back. The people losing money have to be hit all the harder to make up for the people enjoying more income. No, it’s not fair and nowhere near ideal.

The actual impact on demand is fuzzier than that 12:7 ratio as the people with savings, with growing income, tend not to spend all the extra – they don’t need to. Nice for some.

Then there’s the problem of what monetary policy can do when it’s not a simple matter of over-heated demand pushing up inflation. Central bankers from our Philip Lowe to the ECB’s Christine Lagarde have given speeches explaining interest rates don’t work as well when the problem is on the supply side, when lifting rates can actually make the supply problem worse.

And cue the ongoing debate about how much inflation is caused by businesses seizing the excuse of some higher costs to increase their profit margins.

There’s also the underling monetary policy con of ignoring that increasing interest rates – pushing up the price of money – is in itself inflationary.

The authorities get away with that by pegging their target to the CPI – the CPI does not measure interest rates.

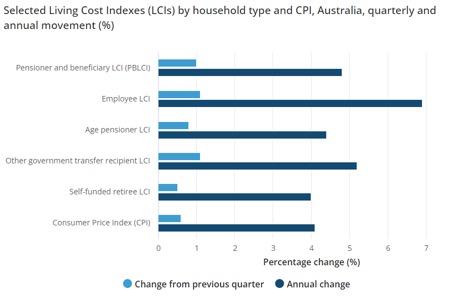

The Australian Bureau of Statistics exposes this policy fraud when it publishes its living cost indexes, showing what inflation really is for various groups of people. As the December-quarter exercise demonstrated, the only people experiencing inflation close to CPI level are self-funded retirees – the ones with the savings.

The RBA’s MARTIN model computes that whacking up the cash rate by 100 points leads to a decline of GDP of about 0.8 per cent over the first year.

So if our GDP is running at about $2.6 trillion, that would be $21 billion in round numbers. Oh, what a coincidence – about the same size as the first year’s stage-three tax cuts, whether Mark 1 or Mark 2.

Yes, fiscal policy – the government adding or removing money from the economy – would be more efficient and vastly fairer than leaving the hard work to monetary policy, but “Look over there! The RBA!”.

Various good souls have suggested alternatives to persecuting the minority of Australians who have considerable net debt. A flexible rate of GST, for example, or a temporary compulsory extra superannuation contribution by individuals, which would have the political benefit of people eventually getting their spending constraint back.

But there’s that word: Political.

In his farewell speech as Governor in September, Dr Lowe gently admitted disappointment that the RBA review did not explore the co-ordination of fiscal and monetary policy “in more depth”. (I would say “at all”.)

“My view has long been that if we were designing optimal policy arrangements from scratch, monetary and fiscal policy would both have a role in managing the economic cycle and inflation, and that there would be close co-ordination,” he said.

“The current global consensus is that monetary policy is the main cyclical policy instrument and should be assigned the job of managing inflation. This is partly because monetary policy is more nimble and it is not influenced by political considerations. Raising interest rates and tightening policy can make you very unpopular, as I know all too well. This means that it is easier for an independent central bank to do this than it is for politicians.”

In my book, that “global consensus” is largely a matter of inertia. Central bankers will central bank, Treasurers will treasure, that’s just the way it is around here.

“Monetary policy is a powerful instrument, but it has its limitations and its effects are felt unevenly across the community,” Dr Lowe confessed.

“In principle, fiscal policy could provide a stronger helping hand, although this would require some rethinking of the existing policy architecture. In particular, it would require making some fiscal instruments more nimble, strengthening the (semi) automatic stabilisers, and giving an independent body limited control over some fiscal instruments. Moving in this direction is not straightforward, but some innovative thinking could help us get to a better place.”

The RBA review – very much a creature of Treasury – did not want to go there whatever submissions it might have bothered to read, whatever opportunity it had to do more than fiddle with process and embroider the bluntest of instruments.

There’s change at the RBA, but no change at all.