Michael Pascoe: The RBA bungle and the huge money wasted on a ‘marginal’ policy

That the RBA is losing money is not news – it was all in the annual report and the costly grey mass of bonds sitting on the balance sheet are there for all to see. Photo: TND/Getty

Remember the Reserve Bank’s $356 billion bond purchase program? Probably not, but it’s costing us $40 billion or so and achieved bugger-all. As far as mistakes go, it’s not a small one.

Of course the RBA doesn’t use language like “bugger-all”. RBA-speak for that is “marginal”.

Specifically, Governor Michele Bullock told the House of Representatives economics committee on Friday: “What we found was that it probably helped to lower long-term bond rates a bit at the margin, maybe 30 basis points, but it wasn’t a first-order impact.”

No, it wasn’t. It was indeed, er, “marginal”. And the cost of that “marginal” impact means the bond-buying program now looks like the sort of performance we’ve come to expect from the Defence Department.

The RBA’s official review of the program in 2022 wasn’t quite so dismissive, then-deputy governor Bullock preferring to say “the review concludes that it broadly achieved its aims”. Faint praise.

Those aims were for it to help a bit. It’s turning out to be an expensive bit. The RBA reckons its bond purchases reduced the cost of Commonwealth and state government borrowing by about $7 billion and maybe reduced our exchange rate by between 1 and 1.4 percentage points.

Well, maybe. Anyone who claims to know with such precision one factor’s influence on exchange rates in a time of turmoil is probably feeding numbers into a model. Anyone who has a model that understands exchange rates would not be working for a living.

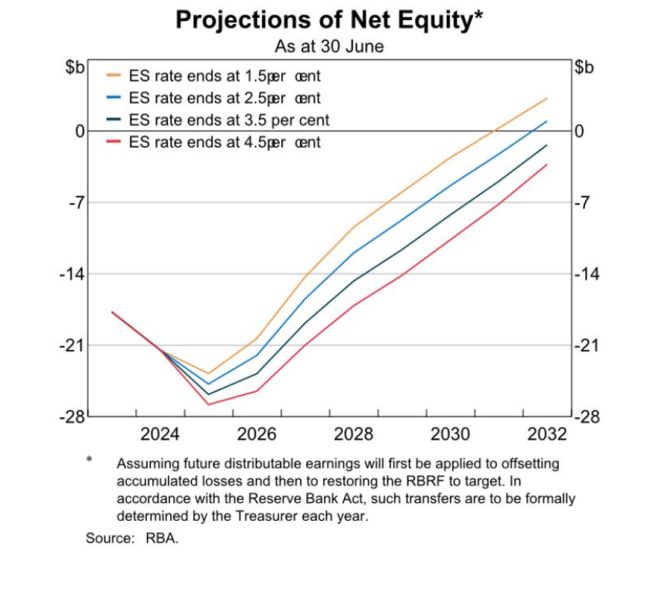

On the other hand, the RBA’s annual report forecast the bank will be $25 billion or so in the red next year, depending on what it does with the cash rate. It will gradually claw its way back to break-even over several years by retaining the fat dividends it otherwise would pay to the government.

To get the bank’s reserves back up to the pre-COVID levels means retaining another $15 billion in dividends. In rough round numbers, call it a $40 billion cost to Commonwealth revenue – nearly enough to pay for a couple of years’ worth of stage-three tax cuts.

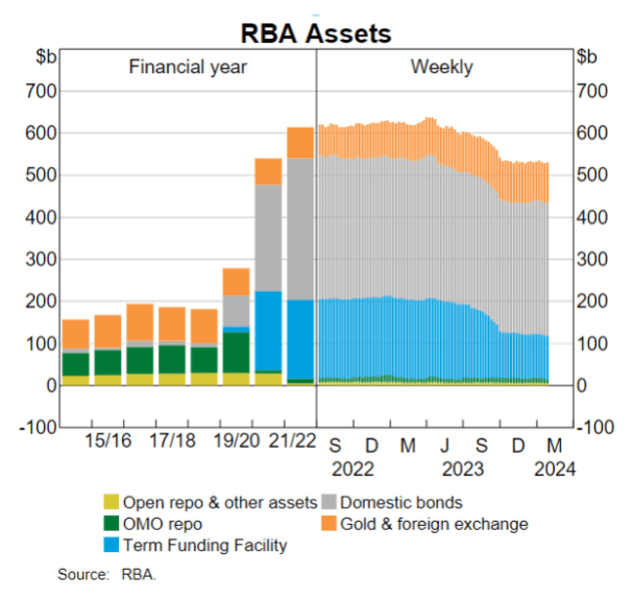

That the RBA is losing money is not news – it was all in the annual report and the costly grey mass of bonds sitting on the balance sheet are there for all to see in the monthly chart pack – but the dismissive tone before the economics committee was surprising when so much money has been blown.

The bond purchase program isn’t the only COVID policy costing the RBA real money – I’ll come back to that – but it was the thing that brought up the subject before the committee.

In central banking circles, the bond purchase program was QE – quantitative easing, the central bank buying bonds with money it created to push more money into the economy, supporting demand.

The opposite transaction, the central bank selling bonds to take money out of the economy, is QT – quantitative tightening.

Allegra Spender, the independent member for Wentworth, wanted to explore if QT might be a tool the RBA could use as an alternative to relying on its primitive bashing of mortgage holders to increase unemployment and reduce demand.

Nah, was the RBA’s answer, QT wouldn’t be worth the effort, so we’ll stick to impoverishing one section of society.

Or, as Governor Bullock actually said: “So, if you flip that (QE) to think about quantitative tightening, if you think that running off the bond portfolio is symmetric then it’s not actually going to do heaps for interest rates.

“The key tool we’ve got is actually the cash rate. That is the primary tool. The QE was introduced at a time when we’d just run out of firepower on the cash rate. That’s why it was used. I don’t think it’s helpful to think of quantitative tightening necessarily as something that you would use instead of interest rates. Interest rates remain our key tool.”

So buying the $356 billion worth of government paper seemed like a good idea at the time because, well, other central banks were doing it and we had run out of other things to do.

Assistant Governor Chris Kent went a little further in dismissing Ms Spender’s question: “The influence of moving from passive QT where we let the bonds just roll off, which is what we’re doing now, to active QT would be designed in such a way as to be about as boring as watching the grass grow or paint dry.”

What neither Dr Kent or Ms Bullock explained to Ms Spender is that the reason the RBA prefers to let the bonds roll off – holding them to maturity and getting the bonds’ face value back from the governments – is a bet on interest rates falling in the meantime, reducing the mark-to-market paper loss the bank is suffering from higher interest rates.

Never mind that, the way the money-go-round works, those hundreds of billions the RBA paid for the bonds ends up coming back to sit in banks’ exchange settlement accounts at the RBA – and the bank is paying 4.25 per cent interest on the ES squillions while it’s only collecting 0.1 per cent (or thereabouts) on the bonds it is holding.

That’s the other way the RBA is losing real money.

And then there’s the $188 billion TFF (term funding facility) the RBA threw our banks, building societies and credit unions to encourage them to lend as COVID hit, the cash that enabled banks to quickly offer those cheap fixed-rate loans.

While the RBA didn’t keep its not-quite-a-promise to civilians that interest rates wouldn’t rise until 2024, it did keep it for banks – three years at 0.1 per cent, effectively free money, on which the RBA is now paying 4.25 per cent in ES accounts.

The remaining $100 billion or so in the TFF will be run off by the end of June, which is occupying the RBA’s attention.

Ms Spender asked if there were circumstances under which the RBA might change its QT model.

Dr Kent: “I think the board has to judge the costs and benefits. The benefits are that you get your balance sheet down a little bit faster and you might reduce interest rate risk, but there are some potential costs as well, depending on how the bonds are being priced at the time.”

Ms Bullock: “The board is keeping this under review. They haven’t ruled it in or out, but, as Chris said, the run-off of the TFF is a hundred billion dollars, I suppose, coming off our balance sheet. We do want to make sure that runs smoothly with markets before we make any decisions, so it’s under review. We’re keeping an eye on it.”

Yes, nothing ruled in or out by Governor Bullock, just as nothing is ruled in or out about what will happen to the cash rate and nobody knows what full employment might actually be. “Forward guidance”, like QE, is no longer a thing for the RBA.

There is another cost to the QE bungle not discussed. Those 30 basis points of cheaper interest rates out along the curve might have been “marginal” to the RBA, but they still would need to be countered as the bank wanted to tighten monetary policy.

It’s arguable that one of the bank’s 25-point rate hikes was necessary to balance the QE stimulus hanging around. Add that to the unnecessary (with the benefit of hindsight) November rate increase and you have half a per cent on mortgage rates today that certainly aren’t marginal for the people pushed to the margin and beyond.

Remember that last week, while Governor Bullock was leaving the cash rate unchanged, the bank was telling us monetary policy was still tightening on households. The Statement on Monetary Policy said interest charges’ share of household disposable income would increase from about 7 per cent to 8 per cent.

My guess that that might mean the share of household disposable income going on mortgage payments would rise from 10 per cent to maybe 12 was apparently wrong. The RBA has previously said it expects that ratio to peak at 10.5 per cent as the last cheap fixed loans roll off. Another 50 points still isn’t marginal.

And that’s just part of why relying on the cash rate to strangle demand is such a primitive, inequitable and brutal policy – but that’s another story.