Alan Kohler: The undemocratic independent Reserve Bank

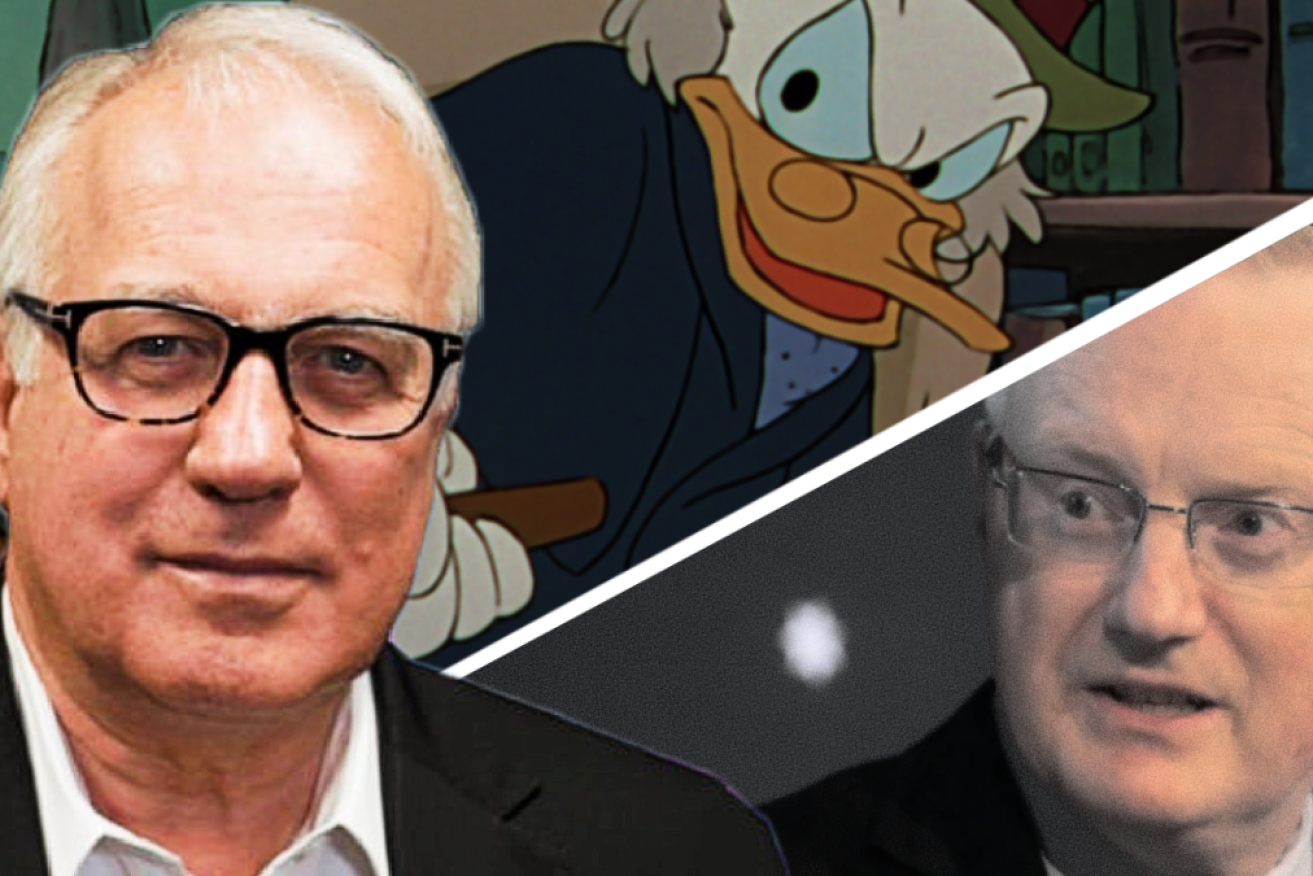

The ghosts of Friedman and Volcker appeared at the foot of Philip Lowe’s bed and turned him into Ebenezer Scrooge, writes Alan Kohler.

Last week’s ‘Statement on Monetary Policy’ from the Reserve Bank makes it pretty clear there are likely to be two more rate hikes, probably in March and April.

Nothing to do with me, said the Treasurer Jim Chalmers, the Reserve Bank is independent.

In fact politicians, both government and opposition, refer so often to the “independent” Reserve Bank as a talisman against being blamed for what it does, that its initials should change to the IRBA.

Except that it’s not independent, not really, or rather its independence is a matter of convenience for politicians, like Pontius Pilate’s.

A better analogy, perhaps, is that the most important economic decisions that affect our lives are made by a machine that treasurers wind up and set going, and then look the other way while they wreak havoc.

Monetary policy is a matter of agreement between the Treasurer and the governor of the IRBA, whom he appoints. After that, it’s independent.

In his new book A Brief History of Equality, Thomas Piketty writes:

“Monetary policy should involve “vast democratic deliberations, in parliamentary precincts and public forums, on the basis of detailed assessments, pro and con, that will allow us to judge the effects of the different possible monetary policies on multiple social and environmental indicators.

“However, the current model of the central banks is definitely not that one: After being appointed by governments … their leaders limit themselves to meeting behind closed doors and deciding among themselves the best way to use immense amounts of public resources.

“You can bet that many battles will have to be fought before the central banks become a genuinely democratic tool in the service of equality.”

The first of the IRBA’s three mandates in the RBA Act in 1959 is to conduct its policies in such a manner as to best contribute to “the stability of the currency of Australia”.

Inflation is not mentioned in any of them.

The other two parts of the mandate are to contribute to “the maintenance of full employment” and “the economic prosperity and welfare of the people”, on which more in a moment.

Contributing to the stability of the currency has come to mean keeping inflation between 2 to 3 per cent.

That target was adopted by the (non-independent) RBA in 1992 and confirmed in 1996 in an agreement between the then treasurer Peter Costello and then (new) governor, Ian Macfarlane.

The deliberate recessions of 1982 and 1991 both predated the IRBA’s explicit inflation target, but it was there in spirit. Those recessions were blatant breaches of the “full employment” and “prosperity and welfare” parts of the mandate.

But by then, only inflation mattered.

The RBA is independent, says Treasurer Jim Chalmers. Photo: AAP

That’s because the world’s economic orthodoxy had put inflation above all other policy aims by redefining “full employment” to be the NAIRU (the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment), which replaced Milton Friedman’s idea of a “natural rate of unemployment” in the late 1970s.

The NAIRU is a mystery of the universe, a bit like quantum particles, but is thought to be about 5 per cent. That’s a level above which, according to theory, inflation accelerates.

In the IRBA’s first decade, “full employment” meant an unemployment rate of 2 per cent, which the new central bank actually achieved.

Since about 1979 the term has meant having a pool of unemployed people to keep wages, and therefore inflation, down. In Australia right now, that would mean another 200,000 people out of work.

Which is why interest rates have been hiked nine times in a row from 0.1 per cent to 3.35 per cent, soon to be 11 times: The unemployment rate, at 3.4 per cent, is 200,000 people below “full employment”, as now defined, so giddy-up.

The real mistake was the cutting of the IRBA cash rate to 0.75 per cent between the GFC and the pandemic, because inflation was below the 2 to 3 per cent target.

What’s wrong with average prices increasing by only 1.5 per cent a year? That was never explained, but the result of trying to get it up to 2 per cent was the encouragement of a huge amount of borrowing which is now coming back to savage those who borrowed to their limits.

But looking over the pandemic abyss in 2020, Philip Lowe and the IRBA board met behind their closed doors and decided among themselves not only to cut the cash rate to 0.1 per cent but also to say they didn’t expect it to change until 2024, which must have seemed like a good idea at the time, but which proved disastrous.

As Thomas Piketty points out, those policies – adopted around the world – simply helped to “further enrich the rich”, and have also burdened the not so rich with debt and, in Australia especially, with very expensive houses.

Last year, the ghosts of Milton Friedman and Paul Volcker appeared at the foot of Philip Lowe’s bed and turned him back into Ebenezer Scrooge.

Maybe the next time there is an exchange of letters between the governor of IRBA and the Treasurer, they can put a 2 to 3 per cent target on “full employment”, and define the “prosperity and welfare of the people” in a way that doesn’t involve crushing them to control inflation.

Alan Kohler writes for The New Daily twice a week. He is also founder of Eureka Report and finance presenter of ABC news