Shattering the Don Bradman myth

State Library of NSW

It used to be said that the Australian people were a tough-minded lot who made heroes of none, and raised no idols, except perhaps an outlaw, Ned Kelly, and Carbine, a horse.

The historian Brian Fitzpatrick who said it died in 1965. Perhaps he overlooked the cricketer Don Bradman. He could not have foreseen the myth-making that churns his memory on.

Another shrine to ‘The Don’ is being completed. Bradman’s childhood home in Shepherd Street Bowral in the NSW Southern Highlands is being restored to the days when young Donald reputedly honed his batting skills by knocking a golf ball into the now famous tank stand.

• ‘Scabrous attack’ on Bradman

A more fitting testimony to The Don’s greatness, however, was the way Michael Clarke’s Australian team clean-swept the Poms in the recent Ashes Test series. It was cricket the Bradman way: clinical, ruthless, and detached with a touch of the school bully about it.

Simply, there is not much about Bradman that was great, or deserving of the adulation heaped upon him.

Bradman would not have stooped so low as to threaten to break a tail-ender’s arm. He was too shrewd for that. But he loved nothing more than intimidating and dominating the opposition.

Like Clarke, he loved to make runs and frighten opposition batsmen with a bit of ‘chin-music’. Clarke has Johnson, but Bradman had Lindwall and Miller whom, with great relish, he unleashed on the Poms after the War.

As England’s 1948 captain Norman Yardley suggested, Bradman was not the nicest opponent. He was unrelentingly tough and not above gamesmanship or letting loose a bumper barrage from his quicks.

But he was the greatest batsman of all time. His Test average of 99.94 far exceeds all others. It is one of the most recognisable numbers in Australian history. The national broadcaster, the ABC, even used it for its post office box.

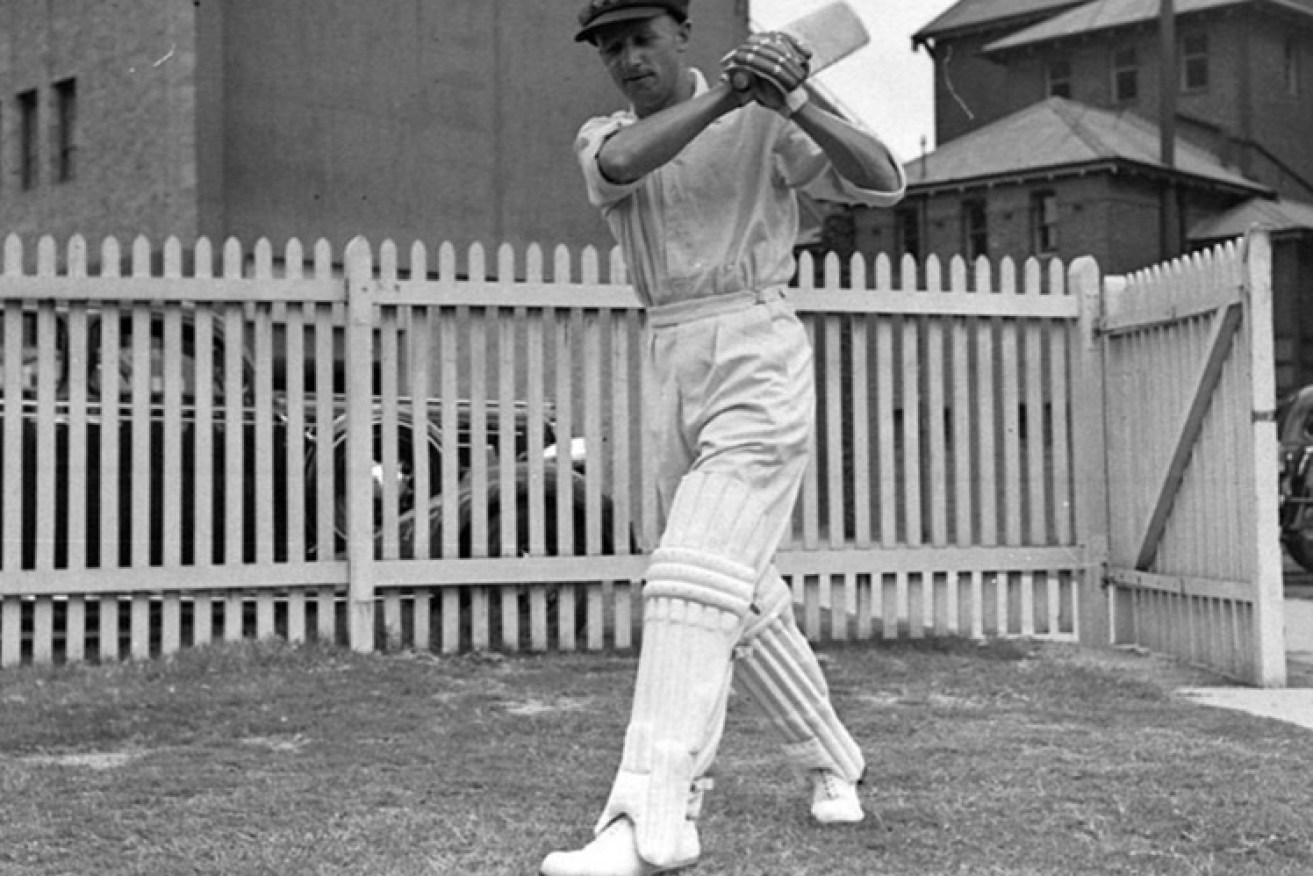

Don Bradman at the crease, NSW, 1932. Photo courtesy of State Library of New South Wales.

When you dig for greatness in The Don, you keep coming back to that number. Simply, there is not much about Bradman that was great, or deserving of the adulation heaped upon him.

Myth would have it that Bradman was a lonely but gifted kid, good with numbers and better with the bat. Other than his mum and future wife, Jessie, his only childhood mates seem to have been the stump, the golf ball and the tank stand.

In reality, Bradman was more comfortable with adults who indulged him. He chose to have few childhood mates of his own age. Whether or not Bradman was in the autism spectrum is open for debate. He certainly lacked empathy and had a near obsessional ability to concentrate intensely for long periods on repetitious tasks.

He learned early that his uncommon batting ability could advance his job prospects. By his mid-teens he was managing Percy Westbook’s Bowral real estate office. By 19 he was a shareholder in a Sydney property development company. In the interim he had scored headline-grabbing mountains of runs for Bowral, Sydney club St George and New South Wales.

Myth has it that Bradman left the real estate game because the Sydney property venture went broke. The fact is he threw it in for cricket. The venture was still going when Bradman was piling on the runs against the Poms in 1930.

A feature of the Bradman personality seen early was an intense acquisitiveness. Cricket enabled him to climb the social ladder and accumulate more money than by selling industrial sites for housing on Sydney’s outskirts. From the 1930 tour he obtained over ₤1600 from endorsements, publishing contracts, and a hefty gift from a wealthy Australian admirer.

On returning to Australia, he left the team in Perth and set off on a promotional romp for his sporting goods employer, Mick Simmons, and General Motors. Again, he was showered with money and gifts, including a new Chevrolet Roadstar car.

He was never one of the boys. Instead, he had an obsessional self-regard which made him unpopular with many of his teammates. Cricket was a means to an end, and he used it to secure employment, which caused problems with Australian cricket’s governing body, the Board of Control.

Ahead of his time

In many respects Bradman was more a sportsman of our age than his. He realised there was more money in journalism and radio commentary than cricket. But the Board had strict controls on players writing for papers during tours, which Bradman breached during the 1930 series.

When fined by the Board, Bradman threatened to take his services to the lucrative Lancashire League, and he threatened to withdraw from the 1932-33 Bodyline series. The matter was only resolved when Associated Newspapers released Bradman from his contract to write a column for the Sydney Sun.

He used this ploy often. It got him a job as a clerk with the Adelaide stockbroker and Board of Control member, Harry Hodgetts.

According to myth, Bradman joined Hodgetts to learn the stockbroking game. In reality, Bradman’s job was cricket. Most of his wage was not paid by Hodgetts, but by the South Australian Cricket Association.

Myth also has it that Bradman was the greatest destroyer of bowling the game has ever seen. In reality, he was its most ruthless destroyer of ordinary bowling.

Bradman was a part-time stockbroker’s clerk and full-time professional cricketer. In a world that still celebrated sport for the love it, Bradman was a ‘shamateur’.

Myth also has it that Bradman was the greatest destroyer of bowling the game has ever seen. In reality, he was its most ruthless destroyer of ordinary bowling and may have struggled against the great West Indian attacks of the 1980s. When the going got tough, Bradman often got out.

It could be argued that his contemporaries, the Englishmen Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe were better all-wicket batsmen, and Bradman had little liking for the fast leg theory of Harold Larwood. On a sticky Oval wicket Larwood had struck Bradman in the ribs in 1930. He took a month to recover physically and was determined not to get hit again.

During the Bodyline series, Larwood and Jardine considered Bradman scared of the quick stuff. So too did some Queensland journalists and players who’d seen him bat against the Aboriginal fast bowler, Eddie Gilbert.

Bradman campaigned against Gilbert and Bodyline. He branded Gilbert and Larwood ‘chuckers’ and Bodyline a blight on the game. He may not have leaked to the press details of the famous Warner-Woodfull exchange during the Bodyline series, though he had good reason for doing so. But he did inform Australian Board members of his views and even wrote a letter to Lord’s; and once again threatened to take his bat to the Lancashire League.

Cashing in

Bodyline may have halved his average, but it cleared the way for Bradman to cash in on his batting ability. By the mid-1930s bodyline was barred and Larwood had been forced from the Test arena. Against far more docile attacks than Cook’s Englishmen faced, Bradman plundered runs.

By 1936 he was Australian captain, selector and considering a move into in cricket administration. He applied unsuccessfully for the plum job of Melbourne Cricket Club secretary in 1939, but was pipped by Vernon Ransford. Not all considered Bradman ideal for the job. As noted by the NSWCA vice-president, Bert Evatt, Bradman lacked the “social charm” and was “intensely suspicious”.

He campaigned to keep white South Africa in the international game against the groundswell movement in favour of a boycott over apartheid.

When the war came, Bradman enlisted but was quickly pensioned out with a bad back. Myth has it that Bradman was almost an invalid, but he used his war years wisely. He campaigned for war bonds and followed in Hodgetts’ footsteps, securing seats on the Adelaide Stock Exchange and the Australian Board of Control.

But Hodgetts was a flawed mentor. For years he had been drawing illegally from his clients’ scrips to stay afloat. In mid-1945 his business collapsed and Bradman was unemployed and out-of-pocket.

Within days, however, he opened his own business from Hodgetts’ premises. For Adelaide’s close-knit establishment, many of whom had lost money in the crash, Bradman was seen to be cashing in on Hodgetts’ demise and their misfortune.

Confronted with their hostility, and the prospect of protracted legal proceedings as Hodgetts’ former clients sought recompense in the courts, Bradman returned to cricket.

The Don playing Sheffield Shield cricket in 1937. Photo courtesy of State Library of NSW

Myth has it that he selflessly gave of his time to almost single-handedly resurrect the game here and in England. Bradman was too self-regarding for that. He returned to the crease to resurrect his reputation after the Hodgetts’ affair.

He was now captain, selector and Board member, and batting with his old ruthlessness against depleted English and Indian attacks. But he was determined to leave his mark as captain. In 1948 he drove his Australian team to be the first to go through an English tour undefeated.

He retired at the end of the ‘48 tour and was knighted in 1949. With his last Test innings in mind, one of Adelaide’s matrons was heard after the event to utter cattishly: ‘Arise Sir Donald Duck.’

Howard made knowledge of The Don a pre-requisite for citizenship and passed legislation to stop the commercial exploitation of Bradman’s name.

He also published his memoir Farewell to Cricket, a retort to those critics who acknowledged his batting genius but considered him self-obsessional and fearful of fast bowing. Old English foes – Wally Hammond, Bill Edrich and Norman Yardley – joined the chorus, writing critically of Bradman’s win-at-all-costs attitude.

A conservative administrator

In the ’50s, Bradman’s attention turned to the game’s administration. He was best in dealing with changes to the rules, and less adept at confronting the challenges posed by decolonisation. Cricket was the most colonial of games and Bradman sought to maintain its white, Anglo-Australian hegemony.

He campaigned to keep white South Africa in the international game against the groundswell movement in favour of a boycott over apartheid. As he explained in the 1990s, one of his great regrets was buckling under to Australian government policy which supported a boycott.

Bradman didn’t see the Packer revolution coming. As Board chairman in the early seventies, he was against paying players their full market value. He was also slow to recognise the commercial value of television and the one-day game.

Packer did, and when the Board refused to grant him exclusive rights in 1976, he bought the game’s best players. When the Board and Packer’s PBL brokered a peace settlement in 1979, Bradman left the Board. He liked to give orders, not take them, and now PBL was in charge.

Business of retirement

In retirement he cashed in on renewed public interest in Bodyline after the 1984 television dramatisation of the 1932-33 series, and he dabbled in the memorabilia market. His determined interest in re-telling his side of the story continued as a spate of biographers hung on his every word in penning their definitive Bradmans, further fuelling the myth. The traits that his teammates criticised as personality disorders were swept under the table.

But with the country’s popular history now being built on nationalistic self-aggrandisement in war and sport, the cult of Bradman’s humble origins and as beleaguered but all-conquering hero fitted in well.

Each year sees a new and usually favourable book on some aspect of the great man’s exploits.

A museum was built in his honour in Bowral, while the conservative Prime Minister, John Howard, declared The Don “the greatest living Australian”. Howard made knowledge of The Don a pre-requisite for citizenship and passed legislation to stop the commercial exploitation of Bradman’s name.

A sex-shop on Adelaide’s Sir Donald Bradman Drive had planned to trade under the banner ‘Erotica on Bradman’ but was stopped by the Bradman Foundation and family.

Howard left public life in 2007 along with the Bradman citizenship question

The Bradman Museum is now the international Cricket Hall of Fame. When it comes to the greats of the game, Tendulkar now out-ranks The Don, according to Hall of Fame patrons.

But the myth grinds on. Each year sees a new and usually favourable book on some aspect of the great man’s exploits. There’s still Shepherd Street and the stump, the golf ball and the tank stand, and the larger-than-life image of a man made great by his batting average for country tourism promoters. The myths are better than the reality for some. But for others, perhaps it is time to acknowledge that Don Bradman was an extremely peculiar Australian.

David Dunstan and Tom Heenan lecture in sports studies at Monash University.