NRL match-fixing scandal just the tip of the iceberg

Getty

The current NRL match-fixing scandal shouldn’t surprise anyone. It’s not the first occasion the code has confronted allegations of this nature.

In 2011, the Bulldogs’ Ryan Tandy was found guilty of spot-fixing and banned for life. Last year, another scandal erupted when Manly’s David Williams was suspended for betting on NRL matches.

Last week, it was Corey Norman, Junior Paulo and James Segeyaro’s turn. They were photographed tucking into a Chinese banquet with Nomad bikie chief Paul Younan and alleged fraudster Rafat Alameddine.

To top off the night, Norman was caught in possession of a prohibited substance.

• NRL promises life bans for match-fixing

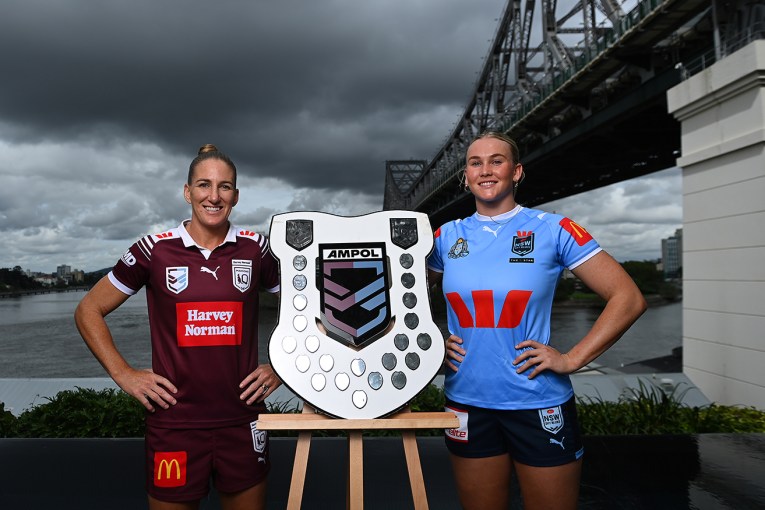

• NSW blow chances as Maroons draw first blood

• ‘It was a try’: Blues’ Josh Morris

NRL CEO Todd Greenberg and the NSW Organised Crime Unit issued warnings to the players about consorting with criminals.

These problems were identified in the 2012 Australian Crime Commission report, Organised Crime and Drugs in Sport. Australian sport was put on notice that career criminals were entering the sports market, trafficking dope to athletes and manipulating the outcomes of contests to profit in legal and illegal betting markets.

Captain Jobe Watson was one of 34 players suspended over the Essendon supplements scandal. Photo: AAP

This warning was lost amid the clamour of the Essendon supplements saga. Stephen Dank and Dean Robinson were just unwitting and bit-players in networks that snaked into bikie gangs and other transnational criminal organisations.

If you scratch deep enough, the peptides industry has links with outlaw bikie gangs and other criminal outfits. The crucial figure in the Essendon saga was a convicted drug trafficker, Shane Charter.

That the club’s administration became involved with such a program at all was an astonishing failure of due diligence.

Gambling is no different. When sports organisations hopped into bed with betting agencies, the writing was on the wall.

Australia, however, has been luckier than most countries. The legal betting market is well regulated. Under-resourced police integrity units attempt to monitor betting across all sports, while the Swiss-based Sportradar advises on any suspicious shifts in betting markets.

It has contracts with the Australian Federal Police and Europol, and was instrumental in uncovering the 2013 match-fixing racket involving a local Melbourne soccer club, Southern Stars.

This case highlighted the transnational nature of match-fixing. The racket was organised by the serial fixer, Wilson Raj Perumal.

Rugby league’s match fixing and betting controversies

In a career spanning almost 20 years, Perumal claims to have rigged soccer games across Europe, the Americas, Asia and Africa, including Australia’s 2010 friendly against Egypt.

As the Southern Stars’ fix suggests, Australians are not immune from sports corruption. In 2014, the world’s leading expert on the topic, Declan Hill, predicted that Australia would be hit by a tsunami of sports corruption. Despite troubles in horse racing, tennis and rugby league, this has not occurred.

However, there is no room for complacency. Though the legal betting market in Australia is tightly monitored and regulated, the illegal offshore one is not.

In 2015, British betting expert Peter Jay estimated the global sport betting market totalled $US3 trillion. Of this, 90 per cent was gambled through illegal channels. This is where the real scope for corruption lies.

Mark Waugh and Shane Warne received cash from an Indian bookmaker in the 1990s in return for pitch and weather information. Photo: AAP

One of the major sources of this revenue is the illegal Indian cricket betting market. Indian bookies are great cultivators of players. Just ask Shane Warne and Mark Waugh. Approximately 80 per cent of this market is controlled by Dawood Ibrahim’s D Company.

Ibrahim has business interests worth $US6.7 billion, according to Forbes, extending from extortion rackets to Dubai real estate. He’s also south Asia’s most wanted man.

His whereabouts are unknown, but usually thought to be in Pakistan or the UAE. He’s got friends in the Pakistani secret service, the ISI, and in the sheikdoms of the Middle East.

In 2003 his bagman, Sharad Shetty, was gunned down in Dubai’s India Club. Shetty controlled D Company’s finances and its emerging interests in the illegal cricket betting market. Shetty’s killer was another career mobster, Chhota Ragan, south Asia’s second-most-wanted man.

It was rumoured that the murder was a play by Ragan for a slice of India’s illegal cricket bookmaking market.

For nearly a decade Ragan ran his operation from Australia. His daughter supposedly attended an Australian university. Police moved in last November when a contract was put out on Ragan’s life by Dawood’s brother, Anees. Ragan was picked up on a flight from Adelaide to Bali, ending one of south Asia’s most colourful criminal careers.

These are the people who rig matches. They run vast, illegal bookmaking networks and have the power and wealth to corrupt sport.

No wonder Todd Greenberg looked so grim.

Dr Tom Heenan teaches sports studies at Monash University.