Alan Kohler: Cost-of-living crisis is all about housing, so it’s probably permanent

Both major parties “lost” the Dunkley byelection because they don’t have an answer to the cost of housing.

They both say they won of course, but that’s politics, and Labor did actually win.

The Labor Party held on because it redirected the proposed stage 3 tax cuts for the well-off towards Dunkley voters, but that was just a short-term, unsustainable teaspoon of sugar, and it was just a redesign of a Coalition policy.

The pressures on government spending will ensure that most bracket creep will have to be kept from now on, and further tax cuts and spending to alleviate the high cost of living will be limited, if not out of the question.

And the Coalition scored a 3.8 per cent two-party preferred swing towards it, but that’s just normal in a byelection.

Diversions vs solutions

Dunkley was described as a “cost-of-living” byelection, in fact all politics these days is dominated by that subject when the talk isn’t about the arrival of alleged rapists and murderers by boat.

But the fundamental cause of Australia’s cost-of-living crisis is housing, and neither party has an answer for it, so they seek refuge in going after supermarkets or, in the case of the Coalition, utes, and emission controls on them.

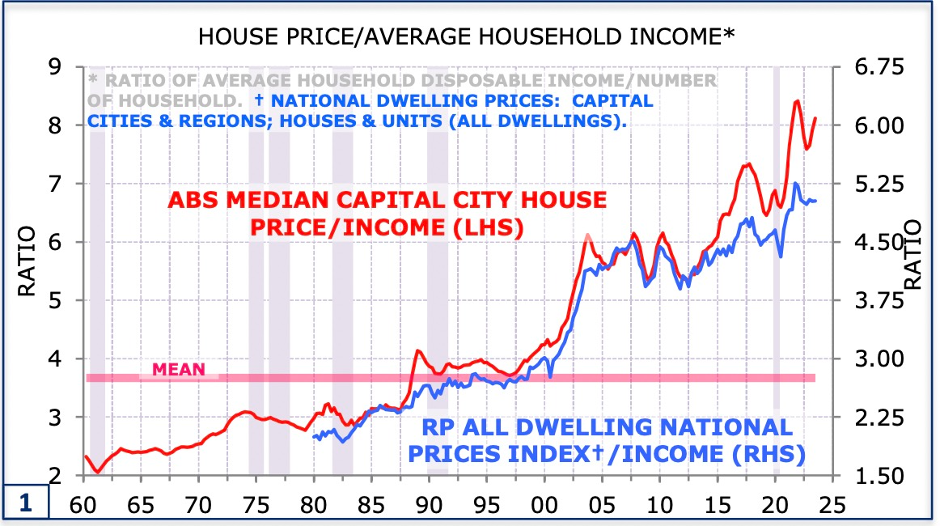

In the past 20 years, the average price of a house in Australian capital cities has gone from three times household income to six times:

If house prices are taken as a multiple of individual incomes as opposed to total household income, the rise is much more because, increasingly, both partners have to work to pay the mortgage.

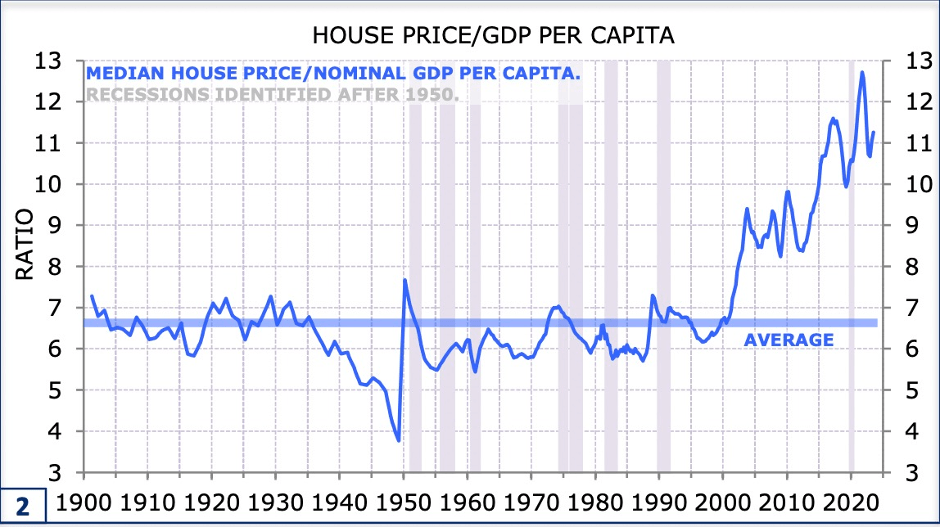

Looked at another way, the median house price has gone from just below seven times GDP per capita, which is proxy for national income per person, to 11 times.

That, plus the fact that the variable mortgage rate has gone from 2.2 per cent to 6.8 per cent in two-and-a-half years, is the cause of the cost-of-living crisis.

But there are no genuine solutions to this that are remotely politically palatable for either party but especially the Coalition.

The distortions in the tax system that encourage housing speculation – negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount – would need to be removed, but both major parties are terrified of doing that and have promised not to.

The apartment solution

Middle-suburban NIMBYism would need to be over-ruled nationally, preferably by some kind of national takeover of planning and zoning, and state and federal governments would all need to get involved in helping developers assemble land parcels for development.

Also, more Australians would have to be persuaded to live in apartments, even though the price of them is increasing at half the rate of houses (84.7 per cent growth over the past ten years versus 40.7 per cent).

And the level of immigration would need to be better tailored to the capacity of the construction industry to house them.

On Sunday’s ABC Insiders, shadow immigration minister Dan Tehan started to lay the groundwork for a political argument about immigration, while saying, of course, that the details will be released in time for the next election campaign.

But the numbers are already coming down from the 400,000-500,000-a-year catch-up intake since the pandemic, so it’s hard to see how that would fly.

In any case, visas are currently issued to satisfy the staffing needs of the health care industries as well as the solvency needs of the universities given insufficient government support, which is unlikely to change with the recent release of the Australian Universities Accord Panel’s report.

Could the level of immigration ever be matched to housing approvals multiplied by 2.5 (the average number of people per house)? Or could the capacity of residential construction be expanded in some way, perhaps by not building new coal mines?

No turning back the clock

That seems unlikely. Population growth will continue to have nothing to do with the number of dwellings being built; if they line up, it’s an accident.

Until there is at least the façade of a plan to improve housing affordability, the major parties will keep losing young voters and their primary votes will decline as baby boomers like your correspondent die off.

But is it even possible to return house prices to the multiple of incomes they were 25 years ago?

Probably not, realistically. It would require a huge national project designed to ensure house prices don’t move for the next 20 years, against the interests of those who own houses, which is the majority of people.

It’s an impossible paradox: To fundamentally improve the cost of living of those who own houses, the value of them would need to stay the same until incomes catch up, which is a long-term project, and not what anybody wants anyway.

And it’s certainly not what any politician would ever say they’re trying to do.

Alan Kohler writes twice a week for The New Daily. He is finance presenter on the ABC News and also writes for Intelligent Investor.