‘Starchitects’: Notre Dame’s design competition one for the ages – or just for Instagram

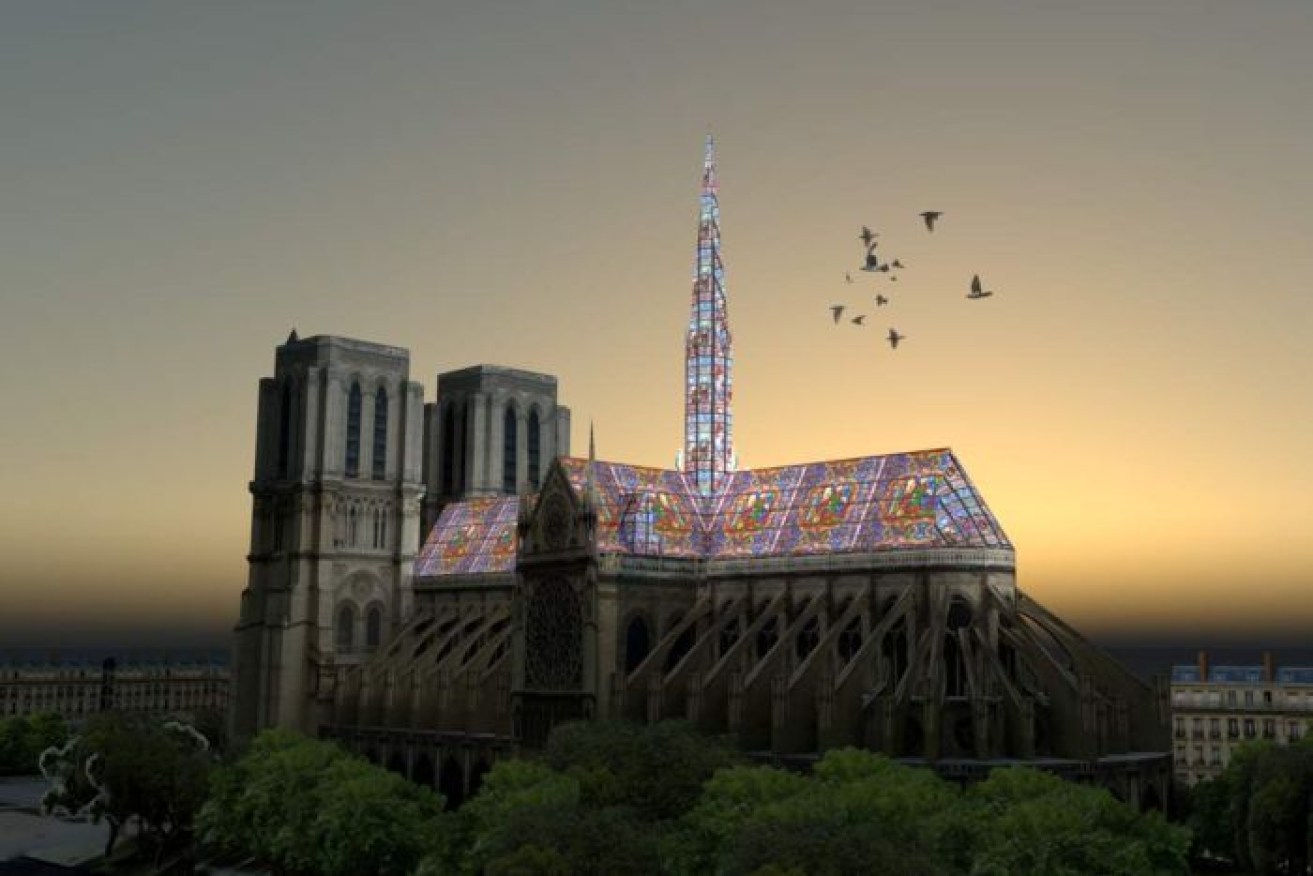

One architect says a stained-glass roof is a way of staying true to the cathedral's origins. Photo: ABC: Alexandre Fantozzi

Architects from around the world have been invited to submit their ideas to a design competition for the ages, after a devastating fire claimed the historic spire and roof of Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral in April.

The cathedral has stood in Paris since 1345, and has over time become a global symbol of French culture, with its story told around the world in Victor Hugo’s 1831 novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Its walls, bell towers and stained-glass windows survived the inferno – thanks to the work of 12th-century architects – and many of its priceless religious relics and artworks were saved.

In the time since the blaze, more than $1.44 billion in donations has been pledged for reconstruction, with much of the money pouring in from France’s richest families and global corporations.

Total, Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy (LVMH) and Apple are among the donating companies, which will also benefit from the French Government’s increased 75 per cent corporate tax rebate on cultural donations in response to the fire.

French President Emmanuel Macron has vowed that the cathedral’s roof and spire will be rebuilt in five years – just in time for the 2024 Paris Olympics.

Soon afterward, French Prime Minister Édouard Philippe announced that France would open an international design competition for Notre Dame’s new spire and roof, presenting architects with a once-in-a-generation opportunity.

Given the significance of the structure — and the vast sums of money devoted to reconstruction — the politics behind the rebuild is bound to be a contentious affair, as pundits from around the world weigh in on what should adorn one of the world’s most famous houses of worship.

While the specific details of the competition are scant, that has not stopped major architecture firms and smaller speculative architects from proposing designs, some of which include topping the cathedral with a physical flame covered in gold-leaf, a tower shooting a beam of light into the sky, and a spire made out of arches and balls.

But Cameron Logan, director of the Sydney School of Architecture’s heritage conservation program, said some these proposals were geared toward the internet age, rather than one that might stretch beyond another hundred centuries.

“Any moment like this – where there’s a great international interest in architecture – presents an opportunity for someone who may not be well known to get an idea out there that is very Instagram-friendly,” Dr Logan told the ABC.

“They can have their speculative design go viral irrespective of any serious engagement with the place and its ongoing life.”

‘These architects are playing the world’s new media’

Architect David Deroo published this concept as a warning against an international competition. Photo: ABC: David Deroo

The construction of Notre Dame came at a time where church spires were often the tallest structures found in a town or city, giving citizens the ability to find their bearings, along with a literal ‘Axis Mundi’, a device that was thought to provide a direct link between the earth and the heavens.

Today, spires have been surpassed by towers made out of glass and steel – with some being constructed to dazzlingly narrow widths – and whoever takes on the Notre Dame project will be serving a country where people who profess no religion are set to make up third of its total population by 2020.

Professor Naomi Stead, an architecture critic and head of architecture at Monash Art, Design and Architecture (MADA), noted that the very nature of the Notre Dame competition spoke volumes about the ways in which the “completely secular” design proposals had responded to today’s image economy.

“Some of these architects are playing the world’s new media by rushing into visualisation to capitalise on the event,” Professor Stead said.

“And we don’t want a one liner [joke].”

But she explained other proposals so far spoke to contemporary concerns about climate change, food production and sustainability – with a number of proposals including apiaries, rooftop gardens, and sites for energy production.

One of the biggest firms to submit a visualisation so far, Foster + Partners – who were responsible for the redesign of Germany’s Reichstag – has proposed a glass and steel intervention over the cathedral.

Foster + Partners completed the Reichstag’s redesign in 1999. Photo: ABC

“Many of the ‘starchitects’ have swooped in and produced concepts, but I have to say that Norman Foster’s [of Foster + Partners] got some form here,” Professor Stead said.

“The glass dome over the Reichstag was an excellent addition symbolically as well as practically.”

Gargoyles and the spire were once controversial additions

Notre-Dame’s famous gargoyles were introduced in the 1840s by Eugene-Emmanuel Viollet-le-duc. Photo: ABC

The last opportunity to significantly remodel Notre Dame came in the 1840s, which was taken by restorers Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus and eminent gothic architecture scholar Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc.

They came onboard following a significant period of neglect, after an attack on the cathedral during the French Revolution left portions of the structure damaged, and saw many of its medieval sculptures looted or destroyed.

While Notre Dame’s foundation stone is believed to have been laid in 1163, only a small percentage of what was completed by 1300-1350 remained after the revolutionary attack.

Curiously, Eugene-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc’s additions, including Notre Dame’s famous gargoyles and the wooden spire that both perished in the fire, were contentious at the time of their introduction.

“In some ways [Viollet-le-Duc’s] Notre Dame is somewhat notorious in the [conservation] literature,” Dr Logan said.

“It was notorious at various points for being overly interventionist and bearing too much of his own mark.”

Dr Logan explained that “best-practice” conservation works were defined by their anonymity, where people should not recognise how much work was being done to conserve something, which he said was found across Italy “on any given day”.

But Dr Logan said whoever gets to write the next chapter of Notre Dame should not ignore the “amazing” story of Viollet-le-Duc’s interventions.

“His work there is of outstanding value and it needs to be carefully considered in the restoration work.”

‘A mythic return to the past is never going to happen’

A selection of blueprints from Notre Dame’s original designs.

The opportunity to revise Notre Dame throws many of the tensions of the architectural world into the public spotlight, debates that often rage behind closed doors on subjects of taste, equity and what exactly gets conserved in our built environment.

Implicit in any conservation project is a study of power, as it will ultimately be a small — often elite — group of people who get to write the next chapter of urban histories.

After Nazi Germany razed about 85 per cent of Warsaw’s historic centre during World War II, Polish architects, conservationists, and art historians looked to 18th-century paintings of the city as the blueprint for the city’s reconstruction.

In Britain, efforts by one of the 20th-century’s most revered architects, Mies van der Rohe, to construct a modernist tower in the heart of London was defeated over a 20-year period with help from the Prince of Wales.

A notorious defender of the classical style, Prince Charles labelled the tower “yet another glass stump”.

“Buildings are palimpsests of various changes and additions over time — and Notre Dame is a perfect example of that,” Professor Stead said.

“I know there’s a school of thought that says it should be rebuilt as it was, but that’s not the technology we’re using today — we don’t use whole oak trees.”

But she added that President Macron’s five-year timeline might risk the chances of a “one-liner” design prevailing, which she said had given conservationists “the world over” cause for concern.

Dr Logan from the Sydney School of Architecture is among them.

“When you’re seriously engaged in conservation processes and thinking, you need to take a much longer view of things — rather than what will make a splash in five years’ time.

“In French public memory, how are the 2024 Paris Olympics going to be [seen] next to Notre Dame in say 300 or 500 years’ time?”

Watch a fly-through animation showing Notre-Dame rebuilt with a replica spire and a glass roof: https://t.co/KMa5ZZrRaU pic.twitter.com/MRmh5ANvSK

— Dezeen (@dezeen) May 17, 2019

Architecture firm wants to turn Notre Dame cathedral roof into a swimming pool https://t.co/9FiQ8W4C5d pic.twitter.com/Hb5Qfnex2O

— New York Post (@nypost) May 18, 2019

Notre-Dame competition an extraordinary opportunity, says Norman Foster. https://t.co/uQxmDZgHbz pic.twitter.com/FPpQgUmckF

— Royal Fine Art Commission Trust (@RoyalFineArt) April 20, 2019