What the South China Sea verdict really means

The Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague has delivered what is, on its face, a landmark ruling that undermines China’s purported claim to vast swathes of the South China Sea.

But one of many problems with the verdict is that China doesn’t care what The Hague, or its neighbours, think about its continued encroachment into the area and associated military presence.

In response to a petition brought by the Philippines, The Hague ruled on Tuesday night (AEST) that:

“There was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources within the [South China Sea].”

The tribunal also found that Chinese law enforcement patrols had risked colliding with Philippine fishing vessels in parts of the sea and caused irreparable damage to coral reefs with construction work. China boycotted the case, saying it would not abide by any ruling.

See more on the growing tensions in the South China Sea

The state-run China Daily newspaper ran a front page headline on Tuesday, before the ruling, declaring “Arbitration Invalid” and has previously warned: “Beijing will not step back, and will not allow what it sees as a wolf-pack scheme to succeed.”

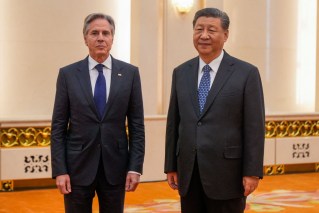

While the United States has not taken an official position on the South China Sea, it is an ally of the Philippines and has been carrying out regular “freedom of navigation patrols” through the area.

Development of Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly Islands Photo: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

Each patrol has been met with an angry response from Chinese military personnel.

Head of the US Pacific command Admiral Harry Harris in February warned that China is “clearly militarising the South China [Sea]”.

He said China’s deployment of surface-to-air missiles on Woody Island in the South China Sea’s Paracel chain, new radars on Cuarteron Reef in the Spratlys and its building of airstrips were “actions that are changing in my opinion the operational landscape in the South China Sea”.

What is the legal impact?

While Philippines’ win in The Hague is a clear legal victory, the decision has little legal impact – and is a result the Philippines government might have preferred to avoid entirely.

It is a principle of international law that sovereign nations must voluntarily submit to court action. As China has not submitted, the ruling cannot be enforced.

But that is not to say that the USA – as global superpower, military rival of China, and dominant navy in the region – cannot employ the ruling to its diplomatic ends. It is likely to use the ruling to increase diplomatic pressure on Beijing.

How did the dispute begin?

The Philippines government under former president Benigno Aquino III requested arbitration with China in 2013 under the Law of the Sea. But the South China Sea dispute has a much longer history – and many more parties. China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia and Brunei all have competing claims to various parts of the South China Sea.

Where is the disputed region?

The South China Sea is a part of the Pacific Ocean spanning approximately 3,500,000 square kilometres. It is located south of China, east of Vietnam and Cambodia, west of the Philippines, and east of the Malay peninsula.

It contains hundreds of islands – including several artificial islands constructed by China, complete with landing strips and weaponry.

China’s claim is also known as the ‘Ox tongue’. Photo: Radio Free Asia

China’s claim, known as the “nine-dash line”, covers most of the South China Sea, including Scarborough Shoal and many disputed islands, reefs and maritime features.

Most of the area is far closer to the mainlands of Vietnam, the Philippines, Brunei and Malaysia than it is to mainland China.

Why are they fighting?

At the heart of the dispute is access to fishing stocks, potential crude oil and natural gas reserves and shipping lanes. And for China, military expansion in the region is a means of challenging US supremacy in the Asia Pacific.

What are the arguments?

China bases its claim on history. It says it has ancient manuscripts that prove it controlled the area in years past. The Philippines’ principal argument in the court case was that the Law of the Sea is based on geological features, not historic areas of control. Thus, it asked the Permanent Court of Arbitration to rule that China’s claim is inconsistent with international law.

What is the verdict?

As noted above, the Hague tribunal found that China’s claim to possession of the region based on history had no legal merit. “The tribunal concluded that there was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources within the sea areas falling within the ‘nine-dash line’.”

What happens next?

In the words of Adjunct Associate Professor Jonathan Bogain: “A tremendous amount of rhetoric from all sides.”

Chinese media has angrily dismissed the ruling as “ill-founded” and “null and void”.

As for the Philippines, the legal action was instigated by the previous Philippines government. I

ts new leader, President Rodrigo Duterte, does not share his predecessor’s enthusiasm for confronting China. The US is its military ally, but China is its largest trading partner.

It will likely try to appease both by reaching some sort of compromise.

As for Australia, it may be emboldened to conduct freedom of navigation operations in the Sea.