How the media manage a story of life and death

When prisoners Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran were moved from Bali to Nusakambangan, Australian media outlets moved reporters, photographers and crews to the city of Cilacap.

The work is hot, information is hard to come by and with the lives of two people on the line, the story is fraught with ethical difficulties too. The ABC’s Greg Jennett reflects on more than a week spent in Cilacap.

Odd is the news story whose conclusion is known at its beginning.

• Mental training for death row inmates

• Kerobokan art auction closed down

• Chan and Sukumaran’s best friend in politics

• Has an inmate bought time for the Bali Nine?

The final wretched weeks in the lives of drug smugglers Chan and Sukumaran are a long and agonising advance towards what seems an inescapable end point on the killing field of Nusakambangan.

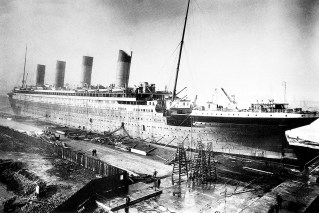

Prisoners arrive on Cilacap. Photo: ABC

The prisoners’ transfer from Bali to Central Java, with all its ugly symbolism, was the last major development and it may stand as the only one until Indonesia’s attorney-general finally calls time for their last three days.

All else – the court appeals, the family visits and the pleas for mercy – simply fill the void between the present and a predetermined conclusion for the Australians.

Reporters covering events in Cilacap this last week know and understand where the story is heading, but nevertheless toil daily to update the story, get footage and make sense of developments for a home audience with an appetite for any detail.

That may sound like a standard news assignment, but reporting in Cilacap is a unique experience.

‘Team Australia’ rallies to support families, Chan, Sukumaran

Few journalists on this assignment are ever likely to again report on executions of Australians abroad and even fewer of them are experienced in the delicate editorial and ethical dilemmas this story throws up.

To understand them, it is necessary to know a little about the “team Australia” outfit operating in Cilacap.

Consul-general to Bali Majell Hind walks through media. . Photo: AFP

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has pulled together a committed band of consular officials, lawyers and advisers based in the Javanese rural and industrial city that stares across to the prison island.

Among their many duties is the care and support of anguished members of the Chan and Sukumaran families.

The relatives, the DFAT team and the media all occupy the same hotel – one of Cilacap’s finest – which would rate a modest three stars in any Australian town about the size of Burnie.

Daily developments are miniscule and information is a scarce commodity.

Incidentally, it is apparent that the media has access to more information than either the Government officials or the families, but as most of it has been published (or is about to be) reporters are generous in sharing what they know.

Gathering facts locally is difficult because there are obvious limits to journalistic inquiry within the highly sensitive “team Australia” hotel.

It is uncomfortable work for anyone with a conscience and a sense of humanity, but Australian reporters will do it each day until the end.

Greg Jennett

When is it appropriate to approach a Chan or Sukumaran family member for “on the record” comments? Rarely – any approach last week could only be intrusive as the families settled into the unfamiliar city of Cilacap and waited for their first visits to Nusakambangan.

Similar reserve is needed with most of the DFAT officials.

Their media strategies are tested against one criterion; is there risk that anything they organise or provide could backfire, upset Indonesian authorities and make Chan and Sukumaran’s predicaments worse?

For this reason, they have little information to meaningfully add.

Aside from supporting the families, the consular team’s local priorities in Cilacap were to forge, within days, new relationships with port officials and the prison governor – a process they had a decade to work on in Kerobokan.

Media face ethical difficulties reporting grim story

So journalists lived and operated around the “team”, but ethically would never be part of it.

The best of reporters would recognise the line between highlighting failures and inconsistencies in the Indonesian justice system (they are many) and cheerleading for the result that the families, the Australian Government and Chan and Sukumaran’s supporters so desperately want.

Media wait in Cilacap for news on Andrew Chan, Myuran Sukumaran executions. Photo: AFP

Also, while others could choose out of loyalty and hope to defer serious thought about the executions, this is not a position the media in Cilacap can take.

There are grim procedures to be read in Indonesian legal statutes for firing squad processes which will eventually need to be explained to readers and audiences (in carefully considered levels of detail).

Reporters in Cilacap have also had to confront planning for the night in question; what to record and where, and if a sight or sound was captured to tell of the shootings – how might they be used?

It is uncomfortable work for anyone with a conscience and a sense of humanity, but Australian reporters will do it each day until the end.

With its large cement and oil factories, Cilacap is an employment hub for hundreds of foreign workers seen trudging to and from their refineries to churn out products of grey and black.

Now Australian reporters find themselves among their number on the southern coast of Java.

We, too, churn out stories in dreary tones of grey and black.

This is no place, no time and no story for anything more uplifting than that.