Rivers in sky: The weather system bringing floods to Qld more likely under climate change

Some 2000 homes are still uninhabitable after flooding in southern Queensland. Photo: AAP

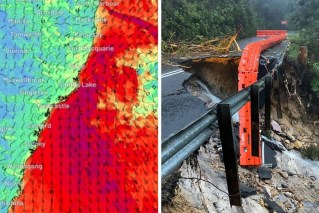

The severe floods in south-east Queensland this week have forced hundreds of residents to flee the town of Gympie and have cut off major roads, after intense rain battered the state for several days.

The rain is expected to continue on Monday, and travel south into New South Wales.

We research a weather system called “atmospheric rivers”, which is causing this inundation.

Indeed, atmospheric rivers triggered many of the world’s floods in 2021, including the devastating floods across eastern Australia in March that killed two people and saw 24,000 evacuate.

Our recently published research was the first to quantify the impacts these weather systems have in Australia, and another study we published in November looked closely at the floods in March last year.

We found while atmospheric rivers bring much-needed rainfall to the agriculturally significant Murray-Darling Basin, their potential to bring devastating floods will become more likely in a warmer world under climate change.

Tweet from @BOM_au

What are atmospheric rivers?

Atmospheric rivers are like highways of water vapour between the tropics and poles, located in the first one to three kilometres of the atmosphere.

They are responsible for about 90 per cent of the water vapour moving from north to south of the planet, despite covering only 10 per cent of the globe.

When atmospheric rivers crash into mountain ranges or interact with cold fronts, they rain out this water with potentially disastrous impacts.

Mountains and fronts lift the water vapour up in the atmosphere where it cools and condenses into giant, liquid-forming bands of clouds. Intense thunderstorms can also form within atmospheric rivers.

A snapshot of water vapour in the atmosphere. Atmospheric rivers are the narrow streamers branching off the equator. Image: Space Science and Engineering Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Three atmospheric rivers last year were particularly devastating.

In January, California was hit with a strong atmospheric river that caused record-breaking rainfall and blizzards. It also triggered a landslide on California’s iconic Highway 1.

In November, British Columbia, Canada was battered with record rainfall that left Vancouver isolated from the rest of the country.

And in March, eastern Australia copped a drenching that led to widespread flooding and $652 million worth of damage.

All mainland states and territories except WA faced simultaneous weather warnings.

Tweet from @BOM_au

What we found

Our recently published research provides the first quantitative summary of atmospheric rivers over Australia.

It’s not all bad news – most of the time, atmospheric rivers bring beneficial rainfall to Australia.

About 30 per cent of south-east Australia’s rainfall comes from atmospheric rivers, including in the Murray-Darling Basin.

Rainfall is vital to this region. The Murray-Darling Basin supports over 500 species of birds, reptiles and fish, and about 30,000 wetlands.

Agriculture in the Murray-Darling Basin contributes $24 billion to the Australian economy.

However, we also found that 30 to 40 per cent of the heaviest rainfall days in the Northern Murray-Darling Basin, where towns such as Tamworth, Dubbo and Orange are located, were associated with atmospheric rivers.

A heavy downpour in Australia’s bread basket might lead to happier farmers during a dry period, but following a wet summer – such as from La Niña – these days are less welcome.

Queensland residents are facing one of the most severe weather systems in a decade. Photo: AAP

La Niña saturates soil

La Niña can play a big role in flooding, as it exacerbates damage wrought by atmospheric rivers.

A La Niña was declared in spring in 2020 and fizzled out by March in 2021. A second La Niña arrived in the summer of 2021 and 2022.

During a La Niña, winds that blow from east to west near the equator strengthen. This leads to cold, deep ocean water rising up to the surface in the East Pacific, near South America, and warm ocean waters to build near Australia.

Warm sea surface temperatures promote rainfall, which is why La Niña is associated with rainier weather over much of Australia.

Soil is like a kitchen sponge. It absorbs water, but once it becomes saturated it can no longer soak up any more.

This is what happened to eastern Australia in the months before the March floods – and when the record-breaking rain fell, the ground flooded.

On March 23, 2021, 800kg of water vapour flowed over Sydney every second.

Our recent research found that from March 17 to 24 last year, NSW experienced an almost constant stream of high water vapour in the atmosphere above from both an atmospheric river that originated in the Indian Ocean and a high-pressure system in the Tasman Sea.

On March 23, more than 800 kilograms of water vapour passed over Sydney every second – that’s 9.6 Sydney Harbours of water in one day.

Likewise, soil moisture in south-east Queensland has been above average since October.

November was Australia’s wettest November on record, with south-east Queensland receiving very-much-above average rainfall.

This meant the ground was already sodden. So when the heavy rain fell this week, Queensland flooded.

The soil in Queensland was already saturated due to higher than average rainfall since October last year. Photo: AAP

What’s the role of climate change?

We also calculated the likelihood of future atmospheric rivers as big as the one in March 2021 flowing over Sydney using the latest generation of climate models.

Earth is currently on track for 2.7 degrees warming by the end of the century.

Under this scenario, we found the chance of a similar weather event to the March floods will become 80 per cent more likely. This means we are on track for more extreme rainfall and flooding in Sydney.

We also know climate change will increase the occurrence of atmospheric rivers over the planet, but more research is needed to determine just how often we can expect these damaging events to happen, including in south-east Queensland.

However, this path is not final.

There is still time to change the outcome if we urgently reduce emissions to stop global warming beyond 1.5 degrees this century.

Every little bit we do to limit carbon emissions might mean one less flood and one less person who has to rebuild.![]()

Kimberley Reid, PhD Researcher in Atmospheric Science, The University of Melbourne and Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.