World’s largest radio telescope set for WA

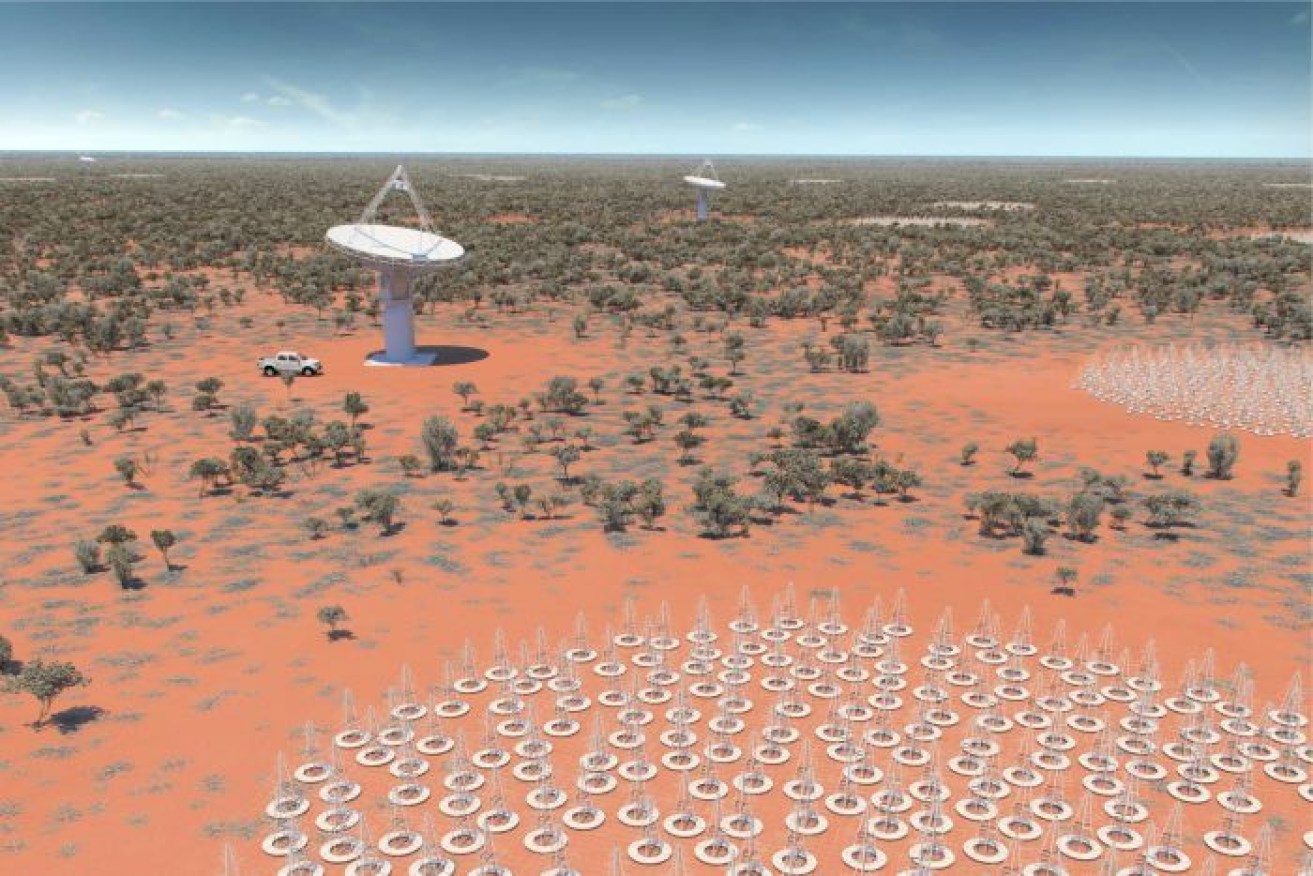

What the Murchison Square Kilometre Array will look like when built. Photo: CSIRO

Scientists and engineers are one step closer to building the world’s biggest radio telescope in Western Australia’s rugged, “radio quiet” Murchison region.

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) is an international, multibillion-dollar project which, when built, will explore the universe in unprecedented detail, listening in on the evolution of the stars and galaxies.

The SKA Infrastructure Australia Consortium, led by the CSIRO, has finished and signed off on the infrastructure designs for the facility, the most significant milestone in the project to date.

The team’s director Antony Schinckel said infrastructure is the backbone of the project and involves everything from supercomputing facilities to roads, water supply and power, everything that is needed to host the instrument at the CSIRO’s Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory (MRO).

“It is an extremely important part of the base of a telescope,” he said.

“Particularly in a remote site, they cannot exist there without all of the infrastructure.

“You have to remember we are going to a site where there is nothing existing now.”

He said it took the team five years to finish the designs, before they were approved late last year.

What is the SKA?

The SKA is a collaboration between 12 member countries and will be built in two locations – Western Australia and South Africa.

It is not a single telescope, but a collection of 132,000 low-frequency SKA antennas, called an array, spread over long distances that is 10 times more sensitive and hundreds of times faster at mapping the sky than today’s best radio astronomy facilities.

When built, it will be the world’s largest public science data project and will generate data at more than 10 times today’s global internet traffic.

But most importantly, it will be powerful enough to detect very faint radio signals from when the first galaxies and stars started forming 13 billion years ago.

Mr Schinckel said it is one of the world’s biggest mega science projects.

“The SKA is one of those top four observatories for the next many decades,” he said.

“Hosting it in Australia and, of course, some of it is being hosted in South Africa, it is an incredible coup for our countries.

“Certainly in Australia it is one of the first real mega science projects.”

The Murchison, 400 kilometres north east of Geraldton, is well known for its arid, pastoral landscapes and is effectively in the middle of nowhere, removed from civilisation – which makes it one of the most radio silent places on earth.

Last year, it gained international attention when a small radio telescope at the MRO detected the first ever signal from the first stars to have emerged about 180 million years after the Big Bang.

Mr Schinckel said the site is ideal because it is naturally radio silent.

“Much like optical astronomy now where you cannot see the stars very well from the city because of the light pollution,” he said.

“Radio astronomy is also really impacted by all the radio pollution around cities, so our mobile phones, our refrigerators, our cars, our computers generate lots of noise.

“So we have got to go as far away as we can from man-made radio interference and this site in Murchison is one of the absolute best in the world.”

Scientists overcome challenges with high tech design

Mr Schinckel said while the location is ideal, it is also the root of the project’s challenges.

“We are getting away from all the man-made radio interference in the cities but with all our own equipment we are installing at the site, we generate a lot more radio noise,” he said.

“So we have to make sure our own telescope cannot see the noise that we are generating with our own electronics.

The planned supercomputing facility. Photo: CSIRO

“A really big challenge is to shield the buildings for example, so that the equipment inside them, the noise that they generate cannot get into the telescope.

“Doing that in a place that is as hot as the Murchison in the summer, you are getting up well into the mid-40s degrees is really a big engineering challenge and, of course, you’ve got to do it all as affordably and sustainably as possible as well.”

The team had to look at cutting edge ways of making everything, including air-conditioners, computers and mobile phones as silent as possible.

“All of those things generate radio frequency noise,” he said.

“It is a matter of putting in lots of continuous steel conducting skins, doors that have special seals on them that contain the noise inside the building.

“By contain here I don’t mean just reducing the levels of noise by factors of tens or even a hundred.

“It is reducing the levels of this radio noise by factors of billions, so it is extremely difficult to get it exactly right and a really big engineering and then construction challenge, it is not just a matter of designing it but building it correctly as well.”

There are 12 international engineering consortia each designing specific elements of the SKA, made up of 500 engineers in 20 countries.

Once all the design packages are completed and approved, a critical design review for the entire project will take place before construction starts, which is expected to be in 2020.

“One of the exciting things as we move into construction in 2020 and 2021 and following years there are some real opportunities there for Australian industries to be involved,” Mr Schinckel said.

-ABC