Clock ticking for endangered lobsters ‘as big as a small dog’

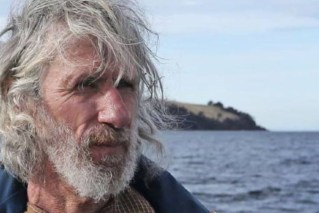

Todd Walsh's family used to hunt giant lobsters for food; now he studies them Photo: The Wilderness Society

Todd Walsh is walking through forest in Tasmania’s north-west on the hunt for an elusive living fossil.

After wading through a river, he disappears into the bush. He later returns with his prize – a Tasmanian giant freshwater lobster.

Known locally as the ‘Lobster Man’, Mr Walsh honed his skills catching these animals for dinner.

Now he dedicates his life to tracking and tagging the threatened species in the name of science.

“It goes back to my great grandfather. My father taught me how to catch them and I’ve got connections going back generations to this animal,” he said.

The giant freshwater lobster – also known as the giant freshwater crayfish – is unique to the island state, can live to the age of 60 and grows to the size of a medium dog. It is the largest freshwater invertebrate in the world.

The specimen Mr Walsh has caught is about 25 years old and, despite being only half the size of a full-grown adult, has claws large enough to break bones.

It is thought there are around 100,000 giant freshwater lobsters, with their numbers declining. Photo: Dan Broun/ABC

Mr Walsh has now tagged more than 1600 of the ancient creatures from 62 different rivers across Tasmania.

His work has gone towards creating the world’s largest database on the bizarre animal.

But the painstaking research has indicated a bleak reality – numbers are dropping, with decades of land clearing and poaching taking their toll.

Professor Alastair Richardson, a retired zoologist who is analysing Mr Walsh’s data, said while poaching was a threat to the large adults, land disturbance such as logging is the big killer for smaller juveniles.

“Sedimentation in streams is a problem for the small animals when they’re very young,” he said.

“They must be able to find a refuge somewhere in the stream that’s often between cobbles between small rocks where they can get into a hiding place, and if those hiding places are crammed with sediment they’re vulnerable to predators.

“If things go on as they are it will be a slow and steady decline.”

A ban on fishing the lobster was put in place in 1998 but the damage had already been done to the population – as a slow-growing animal it takes decades for generations to recover.

“When I first came to Tasmania 40-odd years ago, when you bought your trout fishing licence that entitled you to catch 12 giant freshwater crayfish a day,” Professor Richardson said.

Researchers think there are about 100,000 giant freshwater crayfish left in Tasmania, although no firm number exists because they live underwater and in remote areas. What scientists can state with confidence is the population of large full-grown adults has been almost wiped out.

“We don’t know a lot about the big ones because they were basically decimated over the last century. They grew to six kilograms,” Mr Walsh said.

“That guy there was two kilo,” he added, referring to the specimen he caught earlier in the day.

Recognising the animal’s plight, state and federal governments signed a recovery plan for the giant freshwater lobster in August.

The plan recommends an increase in the size of crayfish habitat reservation in the Arthur, Frankland, Flowerdale and Leven River catchments as being desirable but not critical to the recovery of the species. Mr Walsh said the plan does not go far enough.

“We need to have areas put aside for this animal. There’s no doubt about that if we don’t put these areas aside, they will decline,” he said.

The Tasmanian government said it was preparing legislation to increase penalties around poaching and that “it is important to note that this is a long-term plan that is in its early stages of implementation and we will continue to identify and implement appropriate ongoing actions to assist the survival of the species”.

Professor Richardson said the clock was ticking.

“I think what’s important is that people really do understand what an iconic animal this is. It’s sometimes hard to persuade people that we have something of truly global significance.”

Mr Walsh finishes tagging the two-kilogram lobster, releasing it back into the creek. Hopefully it will go on to a ripe old age.

-ABC