‘Egregious breach’: Teen’s sentence cut after isolation

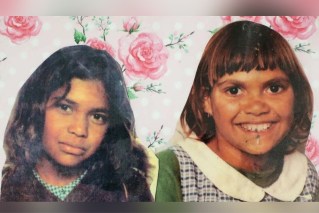

An Aboriginal teen who spent more than two years on remand in a Queensland youth detention centre was in solitary confinement for much of that time. Photo: AAP

Locking up children, ignoring their human rights and focusing on punishment rather than rehabilitation is turning young people into criminals.

That’s the opinion of Indigenous rights adviser Rodney Dillon, who believes it’s exactly what has been happening in Queensland for at least the last decade.

On Friday, an Aboriginal teenager appeared in court having spent more than two years on remand at Cleveland Youth Detention Centre in Townsville.

The court was told that during 744 days in the youth prison, the boy was regularly locked in his cell for more than 20 hours a day.

“Reports tabled in court showing an Aboriginal teenager with an intellectual disability was likely locked in solitary confinement for more than 500 days is among of the most egregious breaches of human rights we have seen,” Mr Dillon said.

“Solitary confinement causes profound, irreparable psychological and physical harm.”

It is not the first time the detention centre has faced scrutiny.

In 2017, an independent review into youth detention in Queensland included reports of children being hogtied and sedated, unnecessary use of solitary confinement and excessive use of force.

At the time, the state government said it was committed to ensuring the safety of children in youth detention and accepted all recommendations.

“It’s become even worse since then,” Mr Dillon said.

“It’s reached the stage where Cleveland should be closed.”

On Friday, the teenager pleaded guilty to sexual assault and rape and was sentenced to four years and six months in custody.

But the judge said due to the severe circumstances in detention, he would only have to serve half that time.

As the boy has “aged out” – turned 18 during his time in youth detention – he will likely spend his final four months in an adult jail, unless there is a successful appeal.

Mr Dillon said the serious nature of the crime did not negate the state’s duty while the boy was in custody.

“It’s torture to put someone in solitary for that amount of time,” he said.

“This is about human rights but it’s also about being human to one another.

“People have not been human to this person.

“I wonder what they expect will happen when he gets out of prison?”

Mr Dillon, a Palawa man and adviser to Amnesty International, said he believed mistreatment of Aboriginal children is rife at most youth detention centres.

“The hatred towards our people and the culture towards our people in Cleveland and other prisons has been there for a long time and this is an example of when it erupts – when you see the point of the iceberg come out of the water,” he said.

In May the Queensland government announced it will build a new youth detention centre in the state’s southeast and is also looking to build another in Cairns, with a proposed site still in planning stages.

The new centres are part of the government’s response to youth crime and follow a raft of controversial laws introduced this year targeting youth and repeat offenders.

Youth Justice Minister Leanne Linard said at the time that new centres are expected to include “therapeutic design elements” and units built to encourage young people, staff and stakeholders to work together.

The new facilities would include consultation and treatment rooms, multipurpose spaces for education and training; and areas for cultural connection.

Ms Linard has been contacted for comment.

1800 RESPECT 1800 737 732

National Sexual Abuse and Redress Support Service 1800 211 028

– AAP