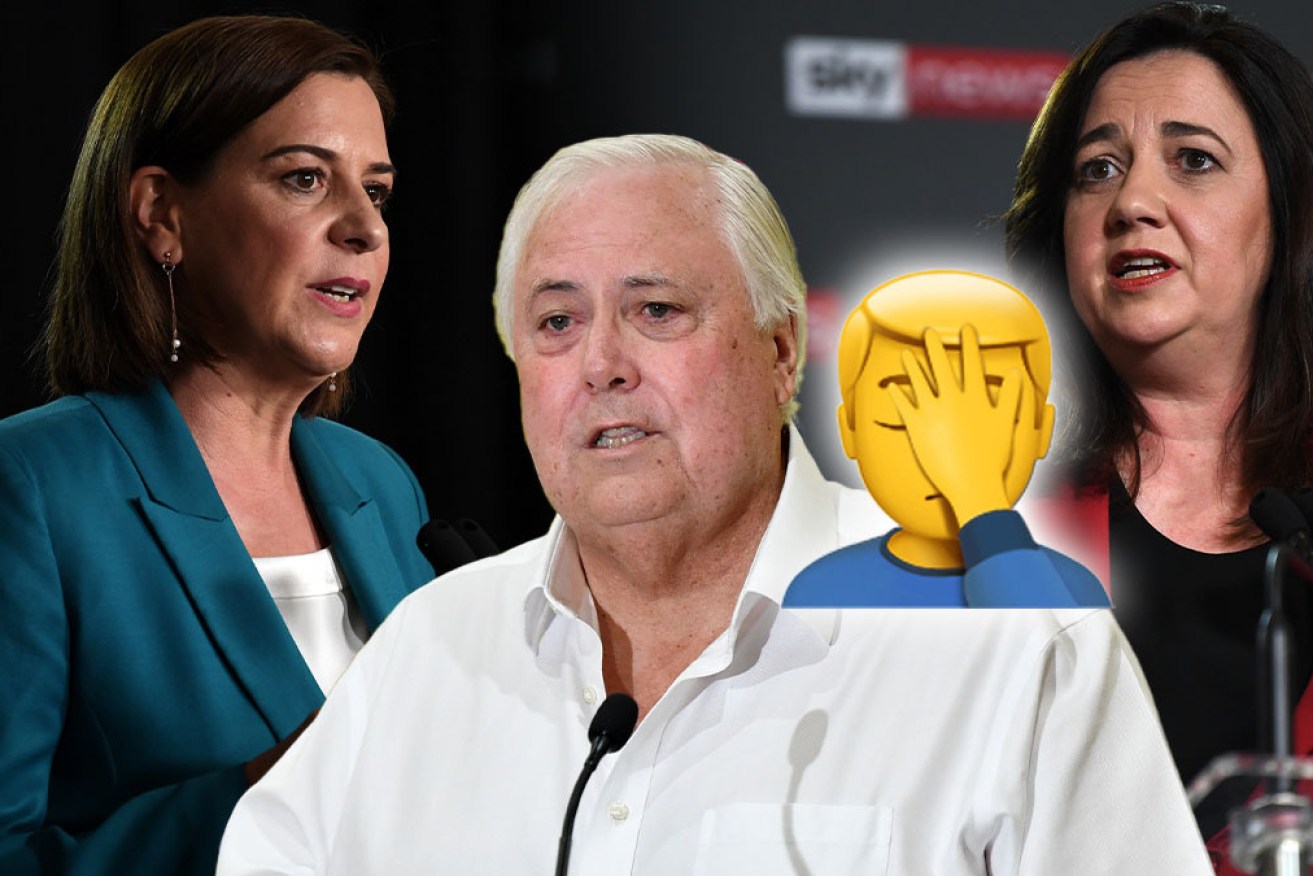

Dennis Atkins: As Queensland votes, Clive Palmer may have told one too many whoppers

The Queensland election has finally arrived. And Clive Palmer has taken centre stage for the wrong reasons ... again.

The money-splashing advertising campaign by serial political disrupter Clive Palmer in this Queensland election offers the winner a compelling case for law reform to ban spreading blatant lies.

Palmer, who is running 55 candidates under the United Australia Party banner, has swamped mainstream and social media with anti-Labor ads featuring a claim Annastacia Palaszczuk’s government will introduce a 20 per cent “death tax” to pay for its election promises.

Following strident denials by the ALP campaign team and Palaszczuk, Palmer admitted he had no proof to back his claim, saying he’d been “leaked” the information from the state Treasury.

“I was called by a public servant from Treasury indicating he was looking at that as an option in reducing debt after the election,” Palmer said after outgoing tourism minister Kate Jones labelled the assertion as “bulls–t”.

Palmer wouldn’t give any further information about when and from whom he’d received his “leak”, preferring to let his money do the talking.

A few days after he brushed away challenges to back his wild claim, Palmer doubled down in his regular and hysterical, double-page, yellow-and-black advertising in the local News Corp daily, the Courier Mail.

The first two pages of the News Corp-owned Courier Mail in Queensland on Friday.

“The cat is out of the bag,” screamed the Palmer ad placed in the final days of the campaign. “Don’t risk a Labor death tax. Labor is furious, their protests prove nothing.”

Palmer is using the number of UAP candidates as a device to pump up how much cash he can splash on the campaign. Spending caps limit the amount of money parties can use for advertising, and other purposes, based on how many people stand for election.

By rolling out 55 candidates, none of whom has the slightest chance of winning a seat, Palmer can stay within the law and outlay over $8 million – based on the $92,000 for each candidate at a state level plus a further $57,000 per candidate limit at a local level.

The latest data published by the Queensland Electoral Commission report that Palmer’s private mining company had donated $4.5 million – made up of 50 different donations – to his candidates.

One of the Facebook ads sponsored by Mr Palmer’s UAP. Photo: UAP

A further series of donations totalling $3.5 million has been moved from Palmer companies to the UAP in recent months. This money will no doubt be spent on the central, virulent anti-Labor advertising such as the “death tax” lie.

This $4.5 million is from the Palmer company Mineralogy and is mostly in the form of cash transfers, although some funds are in-kind wages to pay for company staff to work on the political campaign.

Staff from Waratah Coal, Palmer Gold Coast, Palmer Coolum Resort and Cold Mountain Stud are understood to have been moved across to UAP election work at various times since early August.

Research this week by the Queensland University of Technology’s Digital Media Research Centre found Palmer’s party had spent $100,000 on Facebook advertising alone while the combined effort of the major parties, the LNP and Labor, was $160,000.

This election extravagance mirrors, on a smaller scale, the outlay by Palmer of between $60 and $90 million during the 2019 federal election, most of which was used for blanket anti-Labor advertising in broadcasting and print media as well as billboards and placements across various social media platforms.

Without any laws prohibiting telling lies in political advertising, Palmer can conduct his election campaign outrages without being called to account in any way.

The text message sent to Queensland phones on Monday.

At the moment, the longest standing and tested laws curbing the use of lies in election advertising are in force in South Australia. Similar laws have recently been adopted in the Australian Capital Territory.

The SA law is simple, setting out a basic test for those who make dubious claims.

It states any claim which purports to be a statement of fact is “inaccurate and misleading to a material extent” and any person who “authorised, caused or permitted the publication of the advertisement” would be guilty of an offence.

Ads like those published by Palmer would be caught by the SA laws.

If someone objects to an advertisement, the electoral authorities can issue desist orders and follow up with enforcement orders by the courts is necessary.

If parties felt particularly aggrieved, they could pursue legal redress after an election and perhaps use any untrue advertising as the basis for a challenge in very close results in particular seats, arguing voters were misled.

Various federal and state parliamentary committees have looked at the SA laws and examined if they breached any Constitutional right to freedom of political communication.

Most inquiries have agreed any legislation preventing misleading and inaccurate statements of fact in political advertising “would be an acceptable and proportional intrusion” on any Constitutional constraint.

Interestingly, the Labor Government of Wayne Goss was set to consider truth in political advertising laws 25 years ago after recommendations from the Electoral and Administrative Reform Commission (set up on the say-so of the Fitzgerald Inquiry in the late 1980s).

This reform hit the fence after the Liberal National Coalition took power in February 1996. Given the blatant lies Clive Palmer has told in the last month, this is a reform well worth revisiting.

The experience in SA demonstrates these sensible laws are easily administered and policed and do not hinder robust and willing electioneering.