How the law could permit the standing down of Christian Porter

The pressure to investigate against Christian Porter's fitness to be Australia's top law officer is growing. Photo: Getty

One of the major questions facing the Australian government today is whether Christian Porter should stand down – or be suspended – while an independent investigation is conducted into the historical allegations against him.

Mr Porter rejected this proposal in no unclear terms at Wednesday’s press conference, stating: “If I stand down from my position as Attorney-General because of an allegation about something that simply did not happen, then any person in Australia can lose their career, their job, their life’s work, based on nothing more than accusation that appears in print”.

He went on to say that doing so would render the position of Attorney-General unnecessary altogether, “because there would be no rule of law left in this country”.

But is that true?

Under Australian industrial relations law, the standing down of a public service employee during an investigation into their conduct is not only lawful, but expressly provided for in the legislation.

However, that does not mean that it is always warranted, or that it does not cause the employee harm.

In fact, there has been significant judicial consideration of the potential risks to an employee’s health and career that such a suspension can pose.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has attempted to draw a line under the crisis. Photo: AAP

In 2010, the Federal Court of Australia heard an application by a forensic scientist to end her suspension for alleged misconduct.

The allegations related to poor record keeping, and failing to comply with her employer’s policies.

In the judgment, His Honour Justice Mordecai Bromberg accepted evidence that the employee’s suspension was likely to have a substantial impact on her reputation and her future career prospects.

His Honour also accepted that as a highly skilled professional, it was likely that the suspension – and specifically the associated embarrassment and stress – had affected her health and wellbeing.

When considered alongside the finding that the suspension would not improve the integrity or efficacy of the investigation, Justice Bromberg ordered that the employee be returned to work.

Similarly, the NSW Supreme Court heard an application by a specialist pediatrician to overturn her indefinite suspension.

The basis for that suspension was an investigation into historical (and ultimately unsubstantiated) complaints that she had engaged in bullying and intimidation of her colleagues.

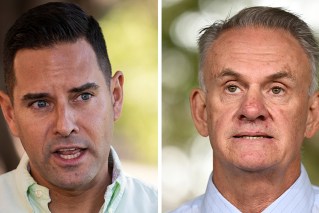

Attorney-General Christian Porter denies the allegations. Photo: AAP

His Honour Justice Stephen Rothman emphasised that in the case of employees who are both senior and highly skilled, it is less likely that their employer has an entitlement to indefinitely require the employee not to work.

The court found this was particularly the case in circumstances where the pediatrician had only accepted the job because she was told that she would be able to establish and run the hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit, and had moved from Canada to perform that work.

Justice Rothman ultimately held that suspending that doctor for longer than was necessary to conduct the investigation was a breach of her employment contract.

What these and other cases tell us is that while it may be appropriate – and sometimes necessary – to stand down an employee while an investigation is under way, the negative connotations of a suspension should not be ignored.

The current predicament involving the Attorney-General Christian Porter is unique in that it involves the highest law officer in the country, and the allegations are some of the most serious that can be levelled at anyone.

Labor leader Anthony Albanese has called for an inquiry. Photo: AAP

In those circumstances, there is an argument that it is appropriate to suspend him until the allegations are disproven or otherwise dismissed.

If that occurs, there are measures that should be taken to ensure that Mr Porter is still provided with due process, and the presumption of his innocence is maintained until proven otherwise.

These measures include that he be provided with the full details and particulars of all the allegations against him, any evidence that is in existence, the opportunity to fully respond to the allegations, and a clear picture of how the investigation will be conducted and by whom.

Another important measure, as emphasised by Justice Rothman in the case of the pediatrician, is ensuring that the suspension is only as long as it needs to be for the investigation to take place.

While the allegations as they stand against Mr Porter are greatly concerning, they are at this stage just that: Allegations.

Indeed, it may be argued that the best way to protect the rule of law in this area is to ensure that no employee, up to and including the Attorney-General, is subjected to an investigation that involves poor processes or a pre-determined outcome.

Giri Sivaraman is Principal with Maurice Blackburn Lawyers