Director Peter Weir flies to the defence of accused spy and filmmaker James Ricketson in Cambodia

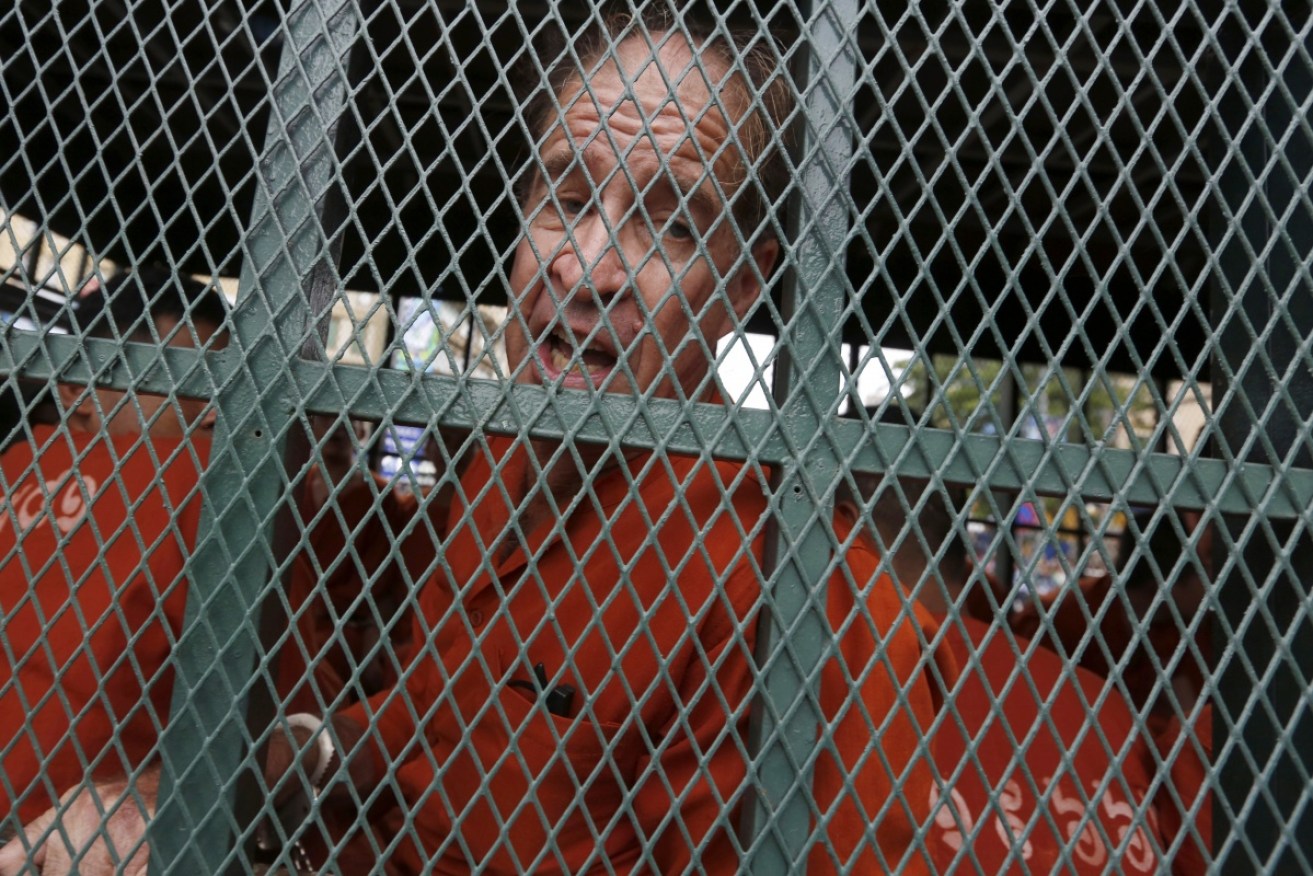

James Ricketson called out from a prison van as it pulled through a throng of media. Photo: AAP

The trial of Australian filmmaker James Ricketson began in Cambodia on Thursday, with a panel of judges grilling a character witness over the accused spy’s finances and links to the Australian Government.

Fourteen months after Mr Ricketson was arrested and charged for flying a photographic drone over a political rally in Phnom Penh, the court opened the trial, in which the accused faces up to ten years in prison on espionage charges that have been panned as disproportionate to the alleged crime.

Acclaimed Australian film director Peter Weir took the stand as the defendant’s first witness, and after a tedious back and forth regarding the specifics of his family and his work, Mr Weir opened a door for the prosecution, which is yet to provide any evidence to support allegations that Mr Ricketson posed a threat to Cambodia’s national security.

Under intense and repetitive questioning over Mr Ricketson’s political leanings, his body of work and his sources of funding, Mr Weir revealed through a translator that the accused had in the past received grants for film projects from “the Government”.

Mr Weir quickly clarified that he was referring specifically to the Australian Film Commission, but the judges and prosecutor seized on the opening, digging into the witness for details of Mr Ricketson’s collaborations with Canberra.

At one point, Mr Weir, who had been candid and anecdotal in more than two hours of questioning, threw his hands in the air and turned to the gallery with raised eyebrows after a judge instructed him to give short, simple answers to questions such as: “How much money has James received from the Australian Government?”

“I’m not his accountant,” said Mr Weir, who went on to become close with Mr Ricketson after mentoring him at film school in the 1970s.

“I’m not his keeper; I’m his friend. How do you describe a friendship? Its not a legal thing.”

Nevertheless, the judges went on probing, and kept the court in session more than an hour beyond schedule.

Mr Ricketson has been a frequent visitor to Cambodia over more than 20 years, making films, doing charity work and criticising the government of Prime Minister Hun Sen, whose Cambodian People’s Party confirmed a monopoly of parliament this week, taking all 125 seats in last month’s general election.

The Australian arrived at the court in familiar fashion on Thursday, calling from the prison van as it pulled through a throng of media personnel.

“There is no victim. There is no complainant. There is no arrest warrant. And there is no evidence,” he said.

“I am confident that a judge will see this, take it into account and find that I am not guilty.”

Legal team argued it was impossible to build a defence

Proceedings began with another bail application, where Mr Ricketson’s legal team argued it was near-impossible to build a defence given the administrative formalities involved with prison visits.

The judges rejected the request, citing the severity of the charges.

Campaigns across Australia have called for Canberra to intervene, with Mr Ricketson suffering from a number of health issues inside the notoriously overcrowded and under-resourced prison.

While Australian policy does not allow diplomats to officially interfere with Cambodia’s judicial process, a spokesperson for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade reiterated that the issue is being discussed “regularly” at the highest levels, with Foreign Minister Julie Bishop meeting with her Cambodian counterpart, Prak Sokhonn, in Singapore on August 4.

After the hearing, Jesse Ricketson, who relocated to Phnom Penh to support his father, said that after months of false starts and private meetings it was a relief to finally have the trial underway.

“We look forward to continuing proceedings on Monday so we can conclude it and get this horrible ordeal behind us,” he said.