The unheard and unheeded Australians who will shape our post-COVID future

The problems facing young Australians aren’t in short supply but, unfortunately, the solutions are.

During the pandemic, there’s been report after report on the problems COVID has caused young people, and the expected short and long-term impacts. But now almost six months into the crisis, young people are rightly asking – where are the solutions?

For young people, public policy is largely out of their hands.

There are no Gen Zers (under 25s) in the Federal Parliament, so young people are completely reliant on decision-makers to engage with them, understand their issues, and take action on the solutions.

We know young Australians rate politicians pretty poorly when it comes to the whole “engaging and understanding young people” thing.

Shadow Youth Minister Amanda Rishworth. Photo: AAP

A 2019 triple j survey found 85 per cent of young people feel politicians aren’t working in their best interests, and over half of respondents to the Mission Australian Youth Survey felt they have a say none of the time in public affairs.

Now, as we navigate the COVID pandemic, politicians are going to have to step it up. Young people are relying on them to find the policy solutions to the biggest challenge their generation is ever likely to face.

The unique elements of the pandemic, namely government restrictions, have compounded the effects on young people of the first recession in 30 years.

Young people bore the economic brunt straight out of the gate.

They disproportionately lost work, with youth-heavy industries such as hospitality, tourism and the arts gutted by government restrictions.

At the same time, young people have been disproportionately ineligible for government support such as JobKeeper.

The flow-on effects are predictable, in particular housing stress.

A report out this week by the Consumer Policy Research Centre showed that in July young people were missing household bill payments at two to three times the rate of the general population, and just over half of young renters were concerned about being able to pay rent.

But the repercussions of the pandemic have been more than just financial – for many young people, the course of their lives has been curbed.

Amssa youth connect centre volunteers sort donated supplies during the pandemic in Melbourne. Photo: AAP

They have missed out on once-in-a-lifetime events like graduations, holiday gap years and milestone birthdays. They are often single so have faced extreme social isolation during lockdowns, while being completed disconnected from their social networks and support.

They have been in limbo as a result of disruptions to their education and training, and their motivation has taken a hit due to remote learning.

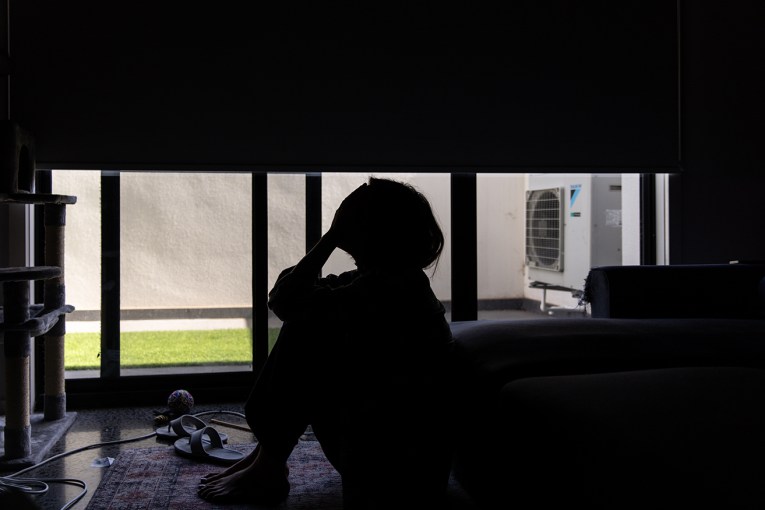

Understandably, as a result of the above challenges and more, young people are feeling the strain.

A recent report by Sydney University’s Brain and Mind Centre predicts a devastating spike in youth suicide as a result of COVID.

The long-term impacts on the young generation are also grim.

There are countless reports predicting that across their lifetime, young people will experience fewer earnings, fewer career opportunities, less housing security, and fewer retirement savings as a result of the pandemic.

Young Australians have had to completely reassess their life goals, dreams and aspirations.

The reality is Generation Z will suffer the consequences of the COVID pandemic for years, decades and potentially the rest of their lives.

The web of interconnected challenges that lay before young Australians cannot be addressed with siloed responses.

Narrow, band-aid policies simply will not deliver the comprehensive, long-term solutions that young people need. The problems facing young people are complex and interrelated, and many are both the cause and effect of each other.

Policy responses to issues like high unemployment and underemployment, increased rates of housing stress and homelessness, and severe mental health challenges cannot be addressed in isolation.

That is why as a matter of urgency we need a National Youth Recovery Strategy.

Former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd launched the National Conversation in Canberra in 2009. Photo: AAP

The last time our country had a National Youth Strategy was 2010.

A decade later, when young people’s prospects are the worst in living memory, we need a reinvigorated national strategy to lead young people through and out of this crisis.

We need a strategy that considers how the myriad of problems interplay, and produces real solutions and policies to successfully address them.

Young people don’t get the front seat when it comes to policymaking, but that doesn’t mean they should be excluded.

A national strategy must be the vehicle for young people to have oversight of and input in their own futures.

The strategy must be co-designed with young Australians, with young people sharing the helm. And I mean genuinely co-designed – not just holding a few focus groups and job done.

It must also include accountability measures and targets, so young people have a mechanism to hold the government to account and ensure their interests are being championed.

Next week is the National Youth Commission’s virtual Youth Futures Summit, in which young people and leaders from across the country will engage in discussion on youth issues.

I hope all decision-makers attending the summit will not just provide lip service and hollow words of encouragement.

I hope the government will deliver young people what they desperately need – a National Youth Strategy that puts youth issues front and centre, and helps to ensure an entire generation is not left behind.

Amanda Rishworth is the Shadow Minister for Youth