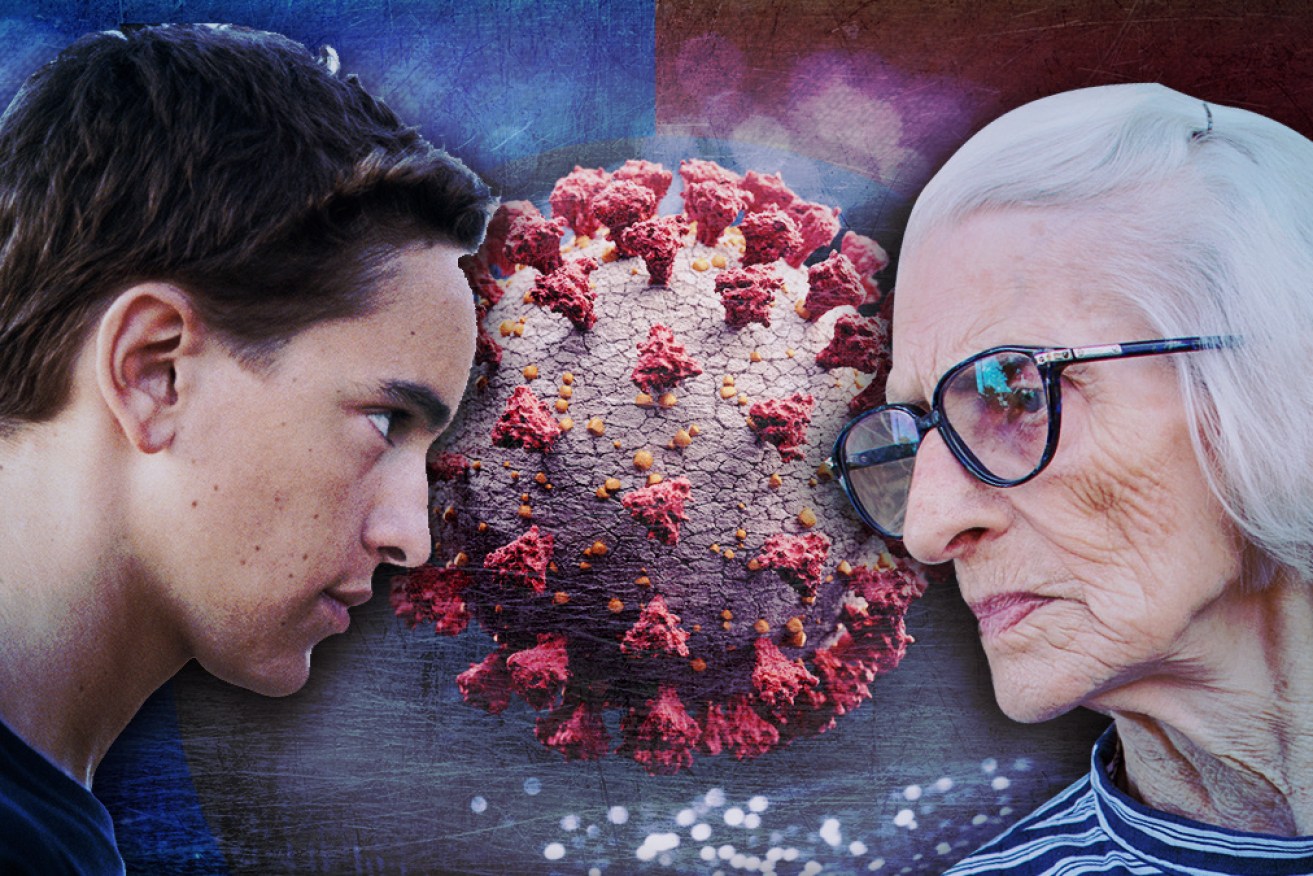

Old versus young: The coronavirus has drawn the wrong battlelines

The debate over the economic effect of the coronavirus is not an old versus young problem. Image: TND

The financial effect of the coronavirus and the measures taken to curb its spread have been pitched as a battle between young and old.

Some commentators describe it as a war between generations, with young people having to sacrifice their freedom, lifestyles and their economic growth and security for older vulnerable people who have already established themselves economically in the world.

This is a misleading argument.

It conveniently papers over the real problem: structural inequities created by successive conservative governments that have embraced neo-liberal economic policy.

Giri Sivaraman. Photo: Supplied

These inequities have impacted all generations and will continue to impact all generations unless we organise our society and economic system in a fundamentally different way.

There is no doubt that older people have benefited from a range of government measures that have enhanced their wealth.

Meanwhile, young people have seen the opposite in their lifetimes, with more casual jobs, a loss of penalty rates, fees for tertiary education and the cost of housing soar.

They have a right to be angry and concerned about their future.

But it isn’t older people that are the problem. To some extent, you would expect older generations to be better off.

They have worked for 40 years, accumulated savings, and contributed to superannuation funds for long periods of time, the intended effect of that being that they would be more secure and less reliant on government benefits in retirement.

However, the reality is that boomers aren’t necessarily more secure. The highest growth of homelessness is in the 55-plus age group.

Furthermore, older women, in particular, are consistently in more precarious positions with reduced super and much more vulnerable to the winds of economic downturn.

The fact is the coronavirus shut-down isn’t just affecting people on generational lines. It has caused a universal economic shutdown.

There is a perverse irony in that some casual workers who have been in long term precarious employment are more secure under the JobKeeper scheme than they have ever been whilst working or trying to find work.

The impact on young people has been magnified due to structural inequities.

Philippa Stanford. Photo: Supplied

Successive waves of anti-union legislative measures have reduced union density and increased insecure work, while the casualisation of the workforce is at an all-time high.

Meanwhile, the basic unemployment benefit, Newstart hasn’t increased, leaving people claiming Newstart below the poverty line.

Giant corporations continue to be able to easily avoid tax obligations or plunder the climate with little consequences.

This will, of course, be the real debt that our future generations have to pay as they watch sea and temperature levels rise.

The economic repercussions show we need to organise our society and address structural inequities for the benefit of future generations.

Many of the measures that have been put in to deal with the economic implications of this crisis should be continued beyond it.

If there was a universal basic income in place we would not have needed the dramatic and sudden introduction of the JobKeeper payments.

Climate emergency

The Newstart or JobSeeker allowance should be maintained at its current rate to avoid people young and old falling into poverty.

Most fundamentally we will have to take immediate and significant measures to combat climate change.

It has been disturbing to see arguments made that older people, the most vulnerable to dying from the coronavirus, should be prepared to face their end so as to prevent young people from a future of debt.

The government does not need to impose austerity measures after the coronavirus threat diminishes and economic recovery begins.

Even more fundamentally, it should not be the case that responding to a health crisis causes such dramatic financial problems.

Surely protecting the health and welfare of all people is a point of living in a society. If it is not meeting this goal then something is wrong.

At the end of the pandemic, we can make a choice to re-organise our finances and economy to support all people and ensure young people have a financially secure future.

Or we can give up and allow conservative economic forces to dictate that some suffer so that others can thrive.

But the final and most crucial step in the re-organisation of our society will be combining those measures with significant steps to combat the real generational threat, which is climate change.

That is the greatest debt we owe to our younger generation and those to come.

Giri Sivaraman is an employment law specialist and Principal with Maurice Blackburn Lawyers. Philippa Stanford is a former senior public servant with the Department of Health and Ageing