It can be tricky knowing left from right in the ALP

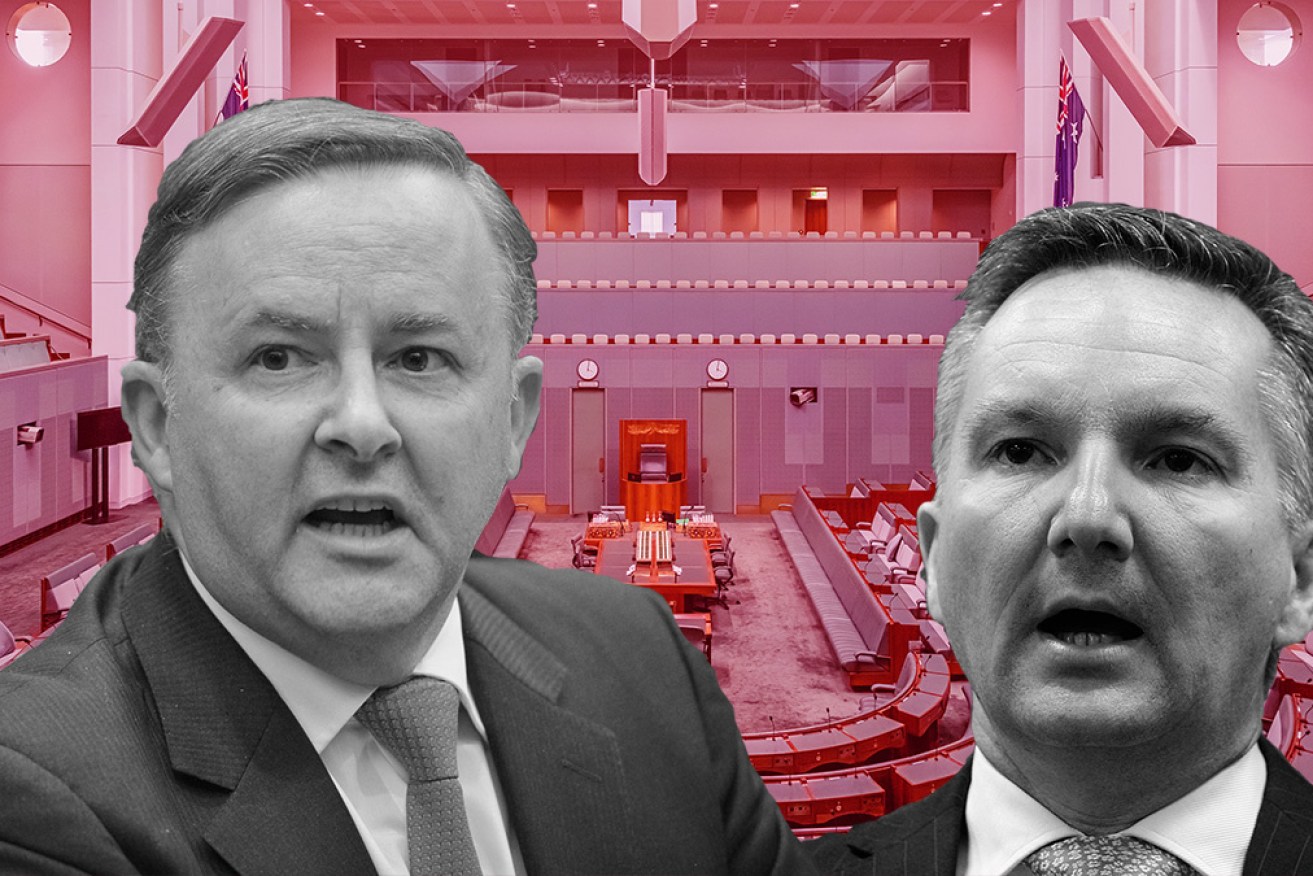

Labor's left faction Anthony Albanese and the right's Chris Bowen squared off for leadership, but only for a day. Photo: Getty

If you’re not a close follower of Australian politics you might be confused by the Labor Party’s contortions over who will become its next leader.

First Anthony Albanese put his hand up, which is not that surprising given he ran against Bill Shorten last time, then the current deputy Labor leader Tanya Plibersek ruled herself out of running for the top job.

Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen was a leadership candidate for 29 hours. Finance spokesman Jim Chalmers said he was thinking about it but eventually said no. Foreign affairs spokeswoman Penny Wong said thank-you for asking, but I won’t be running for leader either.

Why did so many people publicly ‘think about’ running for leader but then end up withdrawing? Because of the factional manoeuvring that was going on behind the scenes.

Factions are groups within political parties that usually form along philosophical lines. In Labor, there are right and left factions at the national level that further break down into left and right factions at the state levels. Sometimes there’s even more than one right or left faction in each state.

There are also factions in the Liberal Party – which we’ll get to in a moment – but Labor’s factions are more formal and have greater influence over how faction members vote, whether that vote is to preselect a candidate, approve a policy, choose which MPs get into the ministry, or elect the Labor leader.

To understand what’s going on with Labor’s leadership contest, it doesn’t matter if you don’t quite get the difference between Labor’s ‘right’ and ‘left’. What’s more important is knowing there’s a constant battle between (and often within) the factions for dominance in Labor’s decision-making bodies and for the leadership positions.

This is what we’ve seen playing out in the most recent Labor leadership contest. Bill Shorten and his Victorian right faction didn’t want Anthony Albanese (from the NSW left) to be elected unopposed to the leadership. So they pressured Chris Bowen (NSW right) to run, but didn’t count on a bunch of MPs from Mr Bowen’s own faction coming out in favour of Mr Albanese.

Even when it became clear that Mr Bowen had no chance of winning the leadership, there were reports he wouldn’t bow out of the race until after nominations were closed to discourage Mr Chalmers (Queensland right) from running. However, once that news emerged, Mr Bowen quickly withdrew from leadership contention.

Mr Chalmers also bowed out once it became clear that the NSW right had decided to back their factional ‘enemy’, Mr Albanese, for the top job.

Then the focus moved to the party’s deputy leadership. When Mr Shorten (Victoria right) was leader, Tanya Plibersek (NSW left) was the deputy. And so it is likely that someone from the right would provide the counterbalance in the deputy leadership to the left-winger Mr Albanese.

Unfortunately the right has been fighting within itself over who that person should be. Mr Chalmers had a good claim because he comes from Queensland, where Labor needs to find ways to reconnect with regional voters there. But he decided on Friday not to run.

Then there is Clare O’Neil, another of Labor’s talented young MPs, who hails from Mr Shorten’s Victorian right. Ms O’Neil’s election as deputy leader would reinforce Labor’s claim to being the party that best represents women. Now that Mr Chalmers has bowed out of the race for deputy, Ms O’Neil’s only competition appears to be her factional colleague from the Victorian right, Richard Marles.

Meantime, Labor’s factions have also been eyeing the party’s leadership positions in the Senate. With the left-winger Mr Albanese holding the leadership in the Lower House, the right would usually lay claim to the leadership role in the Upper House. However this is currently held by widely respected and highly popular left-winger Senator Wong.

An adequate consolation prize may be to place former NSW premier, Kristina Keneally (NSW right), in Labor’s Senate deputy leader role. The only problem with this solution is that a factional warlord from another state, Don Farrell (SA right), holds the deputy role and may not be inclined to give it up to Senator Keneally.

Senator Farrell’s probably still cranky about having to give up the top billing on the SA Labor Senate ticket to Senator Wong back in 2013, which resulted in him being booted from the Senate in that election (he got back in 2016).

Why is all this important? Because the fascinating factional deals that appear to have been done, particularly the arrangement between Labor’s right and left in NSW for Mr Albanese’s leadership, will have a strong influence on any new policies developed by the Opposition in response to its election loss.

This could be a good thing, causing the competing factions to meet in the middle and produce the centrist policies that voters appear to want.

Over in the Liberals, it’s less likely that the party’s factions will find or agree on a middle ground. Just like Labor, the Liberals have right factions – known as conservatives – and left factions – known as moderates. Squabbling between those factions is how Australia ended up with three Liberal prime ministers in the past six years.

The bad news for PM Scott Morrison is those factional fights will only increase following last weekend’s election. The conservatives will point to the results in regional Australia to argue their pro-coal position was vindicated, while the moderates will stress the results in city seats demonstrated the need for the government to take stronger action on climate change.

The only certainty about the factional friction taking place in both major parties is that it will continue.