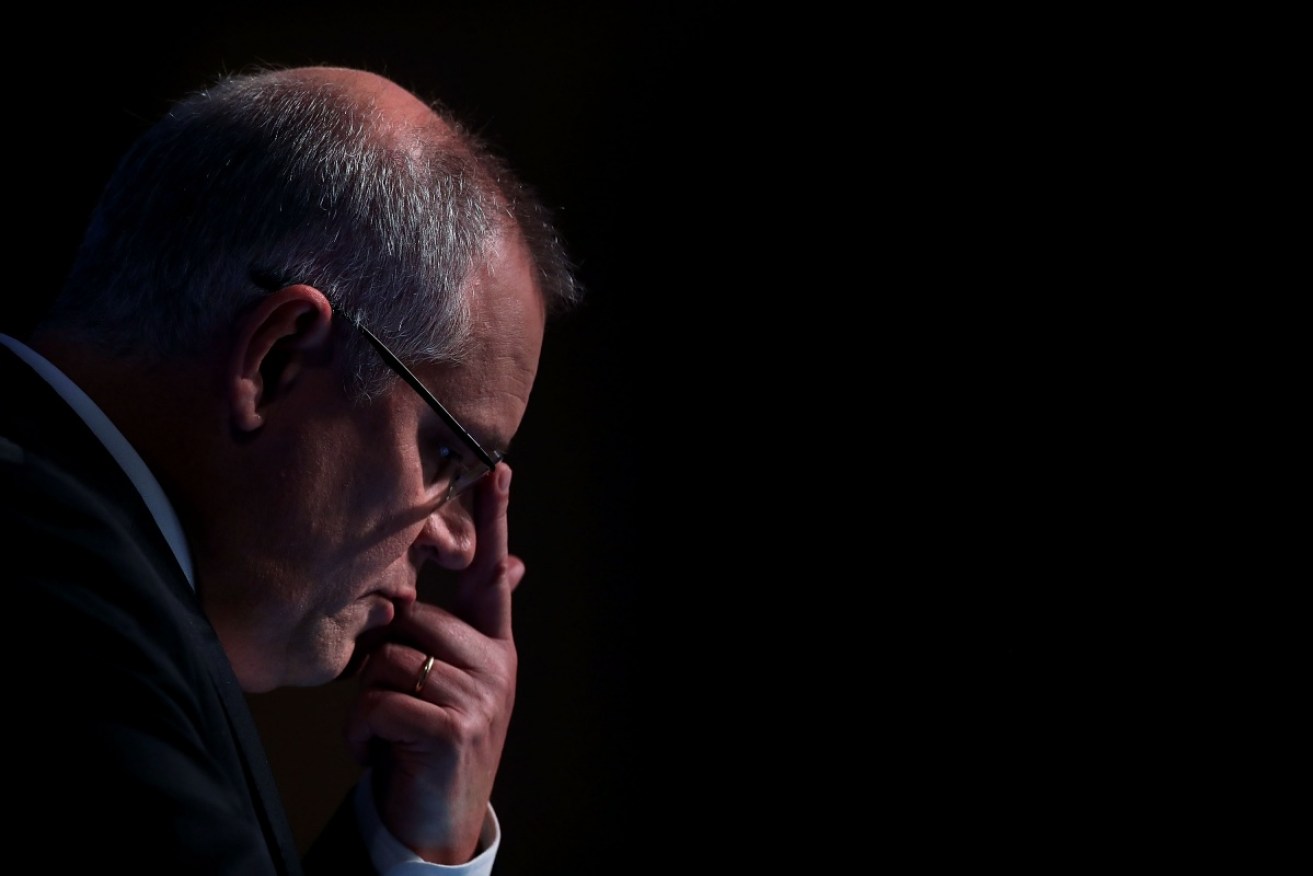

If you really want to stop corruption, don’t follow Scott Morrison

The demolition of Scott Morrison’s Commonwealth Integrity Commission has not taken 24 hours. Photo: Getty

Rarely has a political fig leaf been so quickly and comprehensively blown away, leaving bare Scott Morrison’s shrivelled little excuse of an integrity commission.

The temptation to say it is too great: no, he won’t get it up.

Given the unravelling government’s priorities and fear of its minority status in Parliament, the legislation won’t be debated before the election, after which – barring another Tampa or 9/11 – it won’t be the Coalition’s problem.

But it is important to understand the current government’s fear of a real federal integrity commission and what makes such a body work.

The demolition of Mr Morrison’s Commonwealth Integrity Commission (CIC) has not taken 24 hours. The Morrison/Porter media conference was barely over before The New Daily’s Quentin Dempster was out of the blocks, zeroing in on the lack of public hearings and that “the CIC will not investigate direct complaints about ministers, members of Parliament or their staff received from the public at large”.

The first boss of the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption, Ian Temby, was merciless in an opinion piece on Friday morning. A particularly telling paragraph was:

“As soon as we tapped a politician on the shoulder and asked him to explain dubious conduct, the pressure came on to conduct hearings in private. The pressure to drive the ICAC behind closed doors has continued ever since, although during the period of service of some

commissioners who did not do much – and a couple were notably inactive – little pressure needed to be applied.”

The man who presided over landmark inquiries into Eddie Obeid and other political figures during his time as head of ICAC, David Ipp, told the Sydney Morning Herald the CIC was the “kind of integrity commission that you would have when you don’t want to have an integrity commission”.

Not just a Claytons, but a colander, said Mr Ipp – “it would be really good to make rice in it, it’s got so many holes”.

I’m not sure about the Ipp household’s culinary methods, but you get the message. The NSW ICAC would never have been able to expose Labor’s corrupt powerbroker, Eddie Obeid, under the CIC rules.

Former minister Eddie Obeid was prosecuted for misconduct in public office. Photo: AAP

Just as public opinion and the opposition forced the Liberal Party against its will to hold a banking Royal Commission, the government’s CIC announcement is a begrudging acknowledgement it was on the losing side of the argument.

The government tried to limit damage from the Hayne Royal Commission through a limited time frame and terms that were meant to target industry superannuation funds. The public hearings and skill of the Royal Commissioner and his staff have meant that has not gone according to plan.

The government seems to have learned from that experience. The proposed CIC therefore won’t have any public hearings, won’t be able to listen to whistleblowers or members of the public, can’t look beyond obviously criminal matters and would generally be a waste of money.

Mr Morrison’s NSW Liberal Party – he was state director from 2000 to 2004 and needed a lot of help to be pre-selected – has never forgiven the ICAC for the 10 MPs forced to resign or move to the crossbench over allegedly illegal political donations. Under the proposed CIC’s terms, those 10 would not have been touched.

The NSW ICAC defended so strongly by Messrs Temby and Ipp was inspired by Hong Kong’s ICAC – a body that proved amazingly successful in cleaning up the territory’s endemic corruption.

I was a young reporter on the South China Morning Post during the ICAC’s relatively early days and observed its battles and achievements with amazement. They were real battles with mass purges of police and customs and police storming the ICAC office.

As well as the integrity of the initial staff (including some interesting ex-spooks), a key weapon in cracking open entrenched corruption was unexplained wealth being a crime for public officials. Suspiciously rich ex-pat police officers jailed in Hong Kong tended to snitch quite quickly on their staff sergeants.

Unexplained wealth makes a very interesting law – one that was a step too far for the NSW ICAC.

But the lesson of the HK and NSW ICACs is that corruption, by its nature, can’t be rooted out with kid gloves behind sensitively closed doors while excluding public tip-offs and whistleblowers.

Another lesson is that if existing anti-corruption bodies haven’t exposed and defeated corruption, they’re not going to.

Attorney-General Christian Porter has championed the several existing federal bodies with anti-corruption remits, but their failings have been made clear.

A curious thing: a common argument when greater surveillance of the public is proposed is that “you don’t have anything to fear if you don’t have anything to hide”. That doesn’t seem to apply to the law makers.

The pathetic nature of the pretend CIC could lead one to wonder what government members are afraid of.

It’s hypothetical anyway. The announcement was about taking the government’s official opposition to a CIC off the table before the election. It’s also a botched political job as we’re still left with its official opposition to a real CIC.