Crown-of-thorns starfish eating through Great Barrier Reef in major outbreak

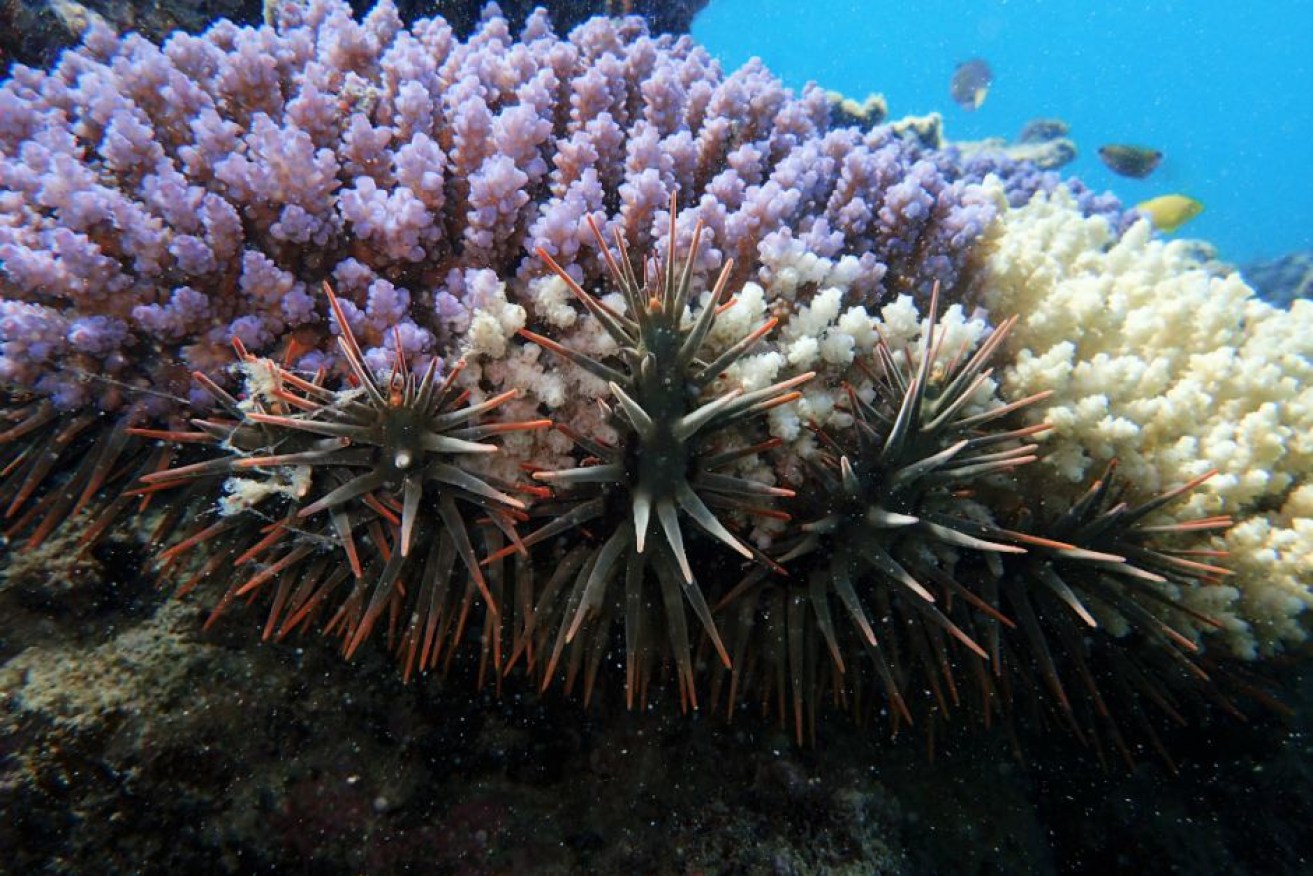

The poisonous barbs of a crown-of-thorns feasting on coral in the northern Great Barrier Reef. Photo: UTS

Thousands of crown-of-thorns starfish are understood to be eating their way through coral in a major outbreak at the southern end of the Great Barrier Reef, as authorities consider how to tackle the problem.

The outbreak on the Swain Reefs off Yeppoon was discovered last year, but the area is remote and hostile, hampering efforts to control the spread of the coral-killing marine animal.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) has confirmed it has been working out how to deal with the outbreak since last year.

The Authority’s director of education, stewardship and partnerships, Fred Nucifora, said monitoring crews went to the area to assess the problem last month.

“They did some pre-emptive culling on the reefs whilst they were there in December and there is another mission and scheduled for January,” Mr Nucifora said.

Images and footage provided by GBRMPA show dozens of starfish covering swathes of the reef.

Dr Hugh Sweatman from the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences would not put a figure on it, but said the number of starfish counted was high.

“Very, very high densities [are] being seen, as high as we’ve seen in the past,” Dr Sweatman said, “and as high as you’d expect to see and there’ll certainly be a lot of coral lost as a result”.

He said the starfish, which also have poisonous barbs that are harmful to humans, engulf the corals to eat them.

“The crown-of-thorns starfish has an extrudable stomach so it lies on top of the coral and it wraps its stomach around the coral,” he said.

“It doesn’t actually break bits off the coral, it just digests the tissue off the of the skeleton … it’s very effective at that.”

The starfish is native to the reef but when numbers explode, the results can be devastating, as thousands of the creatures munch their way through the coral.

“Each starfish eats about its body diameter a night and so over time that mounts up very significantly,” Dr Sweatman said.

The cause of the outbreak has marine scientists stumped. Photo: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

Some ‘control’ or culling efforts underway

Dr Sweatman said the reef could recover but a major culling operation would be needed to give the area the best chance.

The Federal Government and the Association of Marine Park Tourism Operators, runs “control” or culling operations and the Government is seeking tender applications for a third boat dedicated to culling the starfish.

Mr Nucifora said the “control” measures have been focused on specific areas.

“Particularly in the far northern, northern and central sections of the Marine Park, at this point in time, and those reefs that have been identified as high tourism and high ecological value have been primary targets to this point,” he said.

Because the Swain Reefs are so far offshore and are not in the areas identified as priorities for controlling crown-of-thorns outbreaks it is unclear how the major culling program needed would be funded and resourced.

“The complexity with the Swain Reefs location is that they are 100 kilometres to 250 kilometres off the coast between Gladstone and Rockhampton and so they are logistically difficult to access and it’s actually quite a hostile environment to work in,” Mr Nucifora said.

Location of the outbreak puzzling but provides hope

The cause of the outbreak has scientists and the Marine Park Authority stumped.

“That’s the million dollar question to be perfectly honest,” Mr Nucifora said.

Typically scientists link outbreaks of the crown-of-thorns starfish to spikes in ocean nutrients caused by coastal and agricultural run-off into the ocean.

For that reason outbreaks are usually further north and closer to the coast, but the Swain Reefs are a long way offshore and on the southern end of the reef, so it is not known what caused the outbreak.

Mr Nucifora said there were some scientific theories.

“It may be caused by nutrient up-welling from deep ocean waters, but that’s still yet to be fully proven,” he said.

The Swains Reefs, he said, had been hit by a crown-of-thorns outbreak in the 1990s but had managed to recover.

He was hopeful the area could survive again, because of its isolated location at the southern end of the reef system.

“The good thing with respect to that also is that those reefs in the far southern section of the marine park have escaped the significant pressures that have resulted in the last two years from the mass bleaching events,” Mr Nucifora said.

The type of coral present, he said, also gave it a good chance.

“The coral species that that are primarily present in that area are the faster growing our staghorn and plate corals,” he said.

– ABC