Financial exploitation of elderly rife in retirement villages

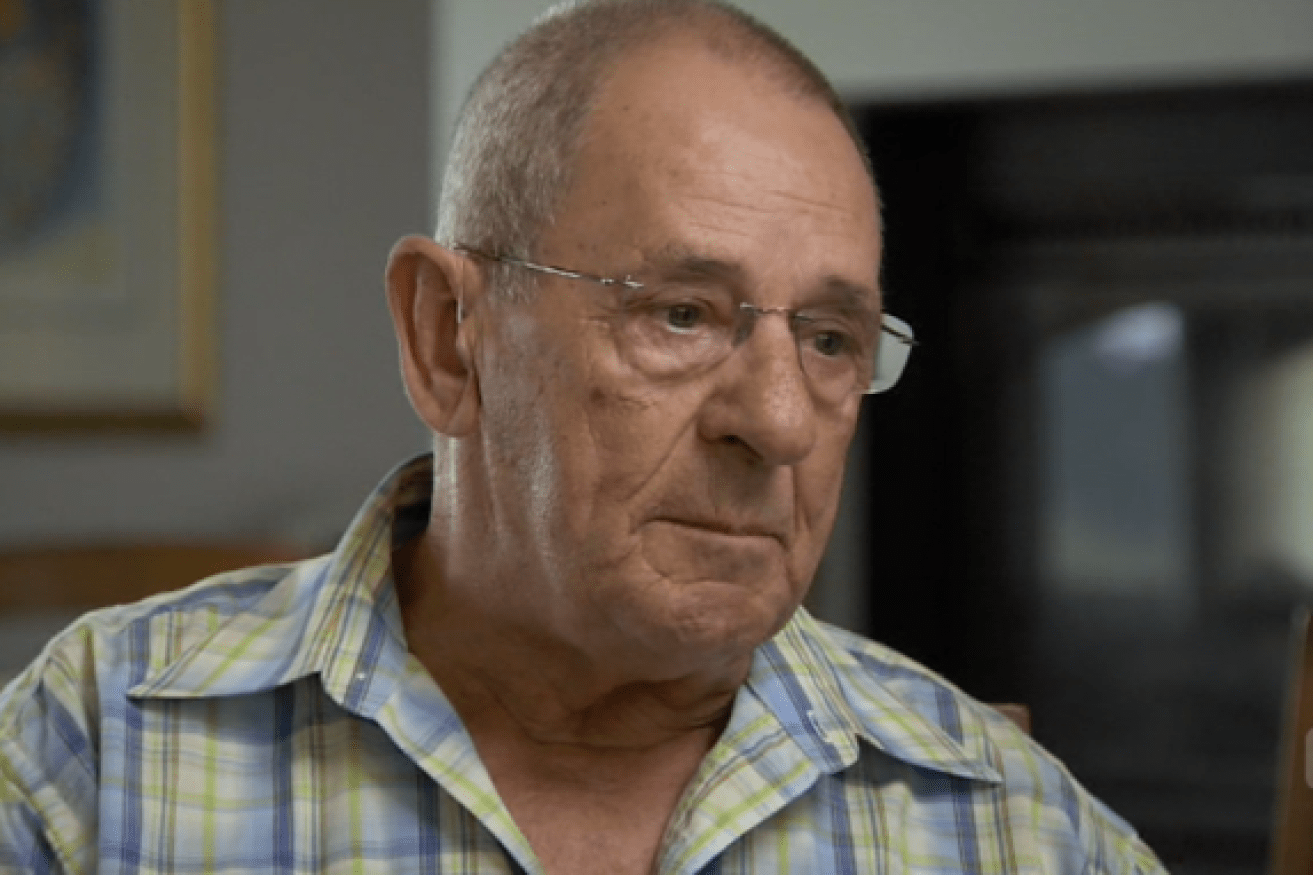

Resident Gary Landells speaks about his experience at an Aveo retirement village. Photo: ABC

Residents of the multi-billion-dollar retirement village industry have described buying into a retirement village as a “financial sinkhole”.

A joint investigation by the ABC’s Four Corners and Fairfax Media into retirement village company Aveo has uncovered exorbitant fees and complex contracts.

One former resident describes Aveo’s business practices as “totally rapacious, I don’t know how they get away with it”.

Fairfax Media and Four Corners spoke to current and former residents, their children, lawyers, former Aveo staff and lobby groups and found several alarming business practices at Aveo – including safety issues, misleading marketing and advertising and property sales.

The joint investigation obtained numerous Aveo contracts, which included clauses some lawyers described as complex and draconian.

Chief executive of the Consumer Action Law Centre Gerard Brody described some of Aveo’s contracts as among the worst he had seen.

“Not only are they over 120 pages in length, they’re dense, they’re hard to understand, they’re legalistic,” Mr Brody said.

“And the financial obligations in them are eye-watering.”

Current and former residents also described the company’s model – which takes an exit fee as high as 40 per cent of the original purchase price, leaving outgoing residents often forking out in excess of $100,000 – as “financial abuse of the elderly”.

Gerard Brody says some of Aveo’s contracts are among the worst he has seen. Photo: ABC

Aveo has 13,000 residents across Australia and is expanding at a rapid rate. It expects to increase its resident numbers to 20,000 in coming years.

Those residents live in just over 11,000 units in 89 villages.

The company is rolling out two new contracts, the Aveo Way – which has exit fees of 35 per cent after three years – and Freedom Aged Care, which charge exit fees of 40 per cent after two years.

An exit fee is unique to the retirement industry. It is calculated as a percentage of the purchase price charged by retirement village operators when a resident sells the property.

Company documents and presentations state a targeted turnover of 10 to 12 per cent of residents each year – or 1200 units a year.

Other large operators have a lower turnover of residents.

Resident evicted after partner dies

Former resident Geoff Richards, 80, helped Aveo reach its stated target to turn over or churn a number of residents or homes a year. The more residents that leave and pay exit fees, the more profit for Aveo.

Mr Richards left the Aveo Veronica Gardens village in the Melbourne suburb of Northcote last year after being unable to negotiate his ongoing residency following the death of his partner of 55 years, Harry Nash.

Mr Nash left his entire estate to Mr Richards, including the retirement village unit they shared.

According to documents seen by the investigation, Aveo began the eviction process because Mr Richards’ name was not on the title, despite being a resident at the village for four years.

“Imagine if a husband and wife, and one of those died and was the only name on the title. Would they throw out the other surviving partner?” Mr Richards said.

Former Aveo resident Geoff Richards, 80, is warning other elderly Australians about retirement villages. Photo: ABC

Documents seen by the investigation show Aveo offered Mr Richards the opportunity to stay on but only if he paid $115,000 in exit fees and signed up as a new resident under a new contract.

He eventually reached a settlement offer with Aveo, which was subject to a confidentiality agreement and non-disparagement clause.

But as a certified practicing accountant he warns other elderly Australians from falling into the retirement village trap.

“If there’s any way that can more quickly separate a person in a retirement village from their money, I don’t know it,” he said.

Mr Richards has since moved to a small unit in a nearby suburb, away from his friends at the village.

“I am now up here in a separate unit, wonderful location,” he said.

“Instead of $6000 a year in body corporate fees, I pay here $1300 a year, yet the same benefits except for an alarm system, which didn’t work [at Veronica Gardens] anyway.”

He also will not have to pay exit fees if he leaves.

Sense of ‘powerlessness’ against corporate giant

Aveo is a financial juggernaut with a market capitalisation of about $1.8 billion.

In 2016, it doubled its profit to $116 million.

The majority of its profits come from exit fees extracted from residents on their departure.

The Aveo Way contracts, which were brought in during 2015, have also been criticised.

Under the program, Aveo is buying back or on-selling freehold properties owned by the outgoing resident as a leasehold, thus reducing the value of the overall property.

Aveo said the new contract offered residents great choice and flexibility, provided residents with clarity and were simpler to understand. But some residents caught in the conversion process disagreed.

Angela Moore is a former resident at Aveo Mountain View in far-north New South Wales.

Former Aveo Mountain View resident Angela Moore says the company wanted to buy all the units that were freehold and turn the village into leasehold. Photo: ABC

She left in 2016 after a two-year stay in the village with her husband Peter went wrong.

On June 20, 2015, Aveo held a meeting for residents that sent chills throughout the community, according to Mrs Moore.

Mrs Moore says at the meeting the residents were told Aveo wanted to buy all the units that were freehold and turn the village into leasehold, known as the Aveo Way.

“The overwhelming feeling was shock, disbelief and powerlessness,” she says.

“Powerlessness in response to a big company saying that they were taking over our homes and ability to sell our homes.”

When the Moores had purchased their unit at the village it was freehold.

The conversion plans left Mrs Moore deeply concerned about the future of the village.

Mrs Moore believed if Aveo bought more than 50 per cent of the units, it would devalue the village and the residents would lose power.

She and many others believed Aveo could then set strata fees to force out the rest of the owners.

The process left Mrs Moore so upset she and Mr Moore decided to leave.

“We still lost a considerable amount of money. But we did move at a time and in a circumstance where financially we were able to recover somewhat but … the move took a lot out of Pete physically,” Mrs Moore said.

“Pete passed away within six months of us moving.”

Residents feel safe, secure: Aveo

Aveo declined to be interviewed for the story.

In answers to a series of questions, Aveo said it did not push residents to convert to The Aveo Way, nor did it churn out residents.

It said national satisfaction surveys conducted within its villages revealed most residents felt safe and secure in the village.

It said it was standardising its contracts to improve the terms and conditions for residents to give certainty.

However, the investigation saw documents which showed Aveo was drastically increasing the resale price of leasehold units.

In one Aveo village in Sandringham, Melbourne, Aveo is offering to buy one-bedroom freehold units for $240,000 while marketing Aveo Way leases over one-bedroom units in the same village for $600,000.

Mr Brody said some residents may want to exit, but find the cost of doing so prohibitive.

“When it comes time to exit, some people can feel trapped,” he said.

“It’s a bit like a financial prison. These fees are too high to enable them to exit, move into aged care, or back close to relatives and family.”

-ABC