Revenge porn ‘spreading like wildfire’: How do we stop it?

AAP

The federal opposition says it would consider new laws against “revenge porn” after it emerged the main police powers to tackle the growing problem were created 12 years before the first iPhone.

Rocketing smartphone use and the popularity of social media is allegedly causing revenge porn to “spread like wildfire”, with practitioners – often jilted men – publishing explicit images of former lovers online to embarrass, harass or blackmail their victims.

Some people have also had pictures stolen from social media profiles and maliciously posted to pornographic sites without their consent.

Dozens of websites around the world are hosting the material, often anonymously and well beyond the reach of victims who try to get highly compromising images removed.

‘Devastating’

Australian Federal Police acknowledges that revenge porn can be “devastating” for victims and says it is aware of cases where images have been stolen from social networks and shared on websites.

But it insists it does not investigate revenge porn or malicious reposting, and recommends victims contact the websites concerned in the first instance.

That leaves state and territory police as the lead investigators in cases that usually span international borders and involve highly secretive website operators that law enforcement agencies around the world have struggled to combat.

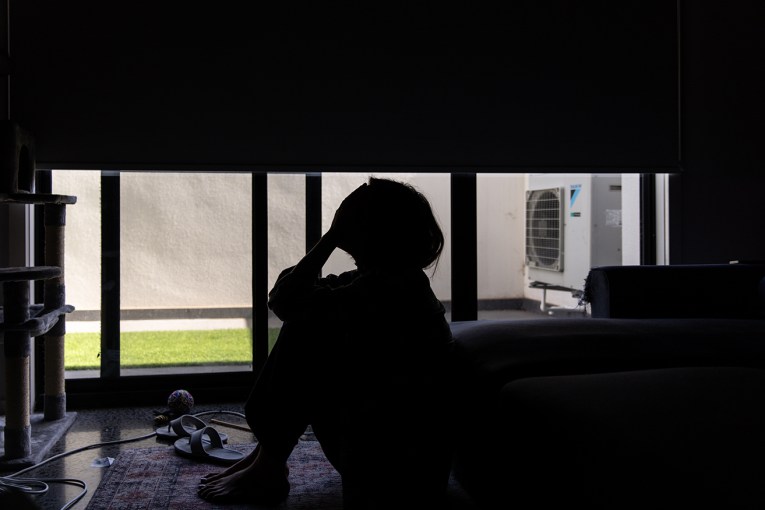

Revenge porn laws need to be updated, says activists. Photo: AAP

Victim’s view

Alleged revenge porn victim Bekah Wells, an American who runs the Women Against Revenge Porn advocacy group, says: “Revenge porn is spreading like wildfire but most people don’t realise it because the majority of victims are not going to announce when they’ve been victims.”

Ms Wells, who lives in Florida, claims an ex-boyfriend maliciously posted intimate pictures of her online in 2010.

Australia, like most nations, has no laws specifically created to combat revenge porn or malicious reposting – which remain relatively new phenomena.

Victoria is the Australian state that has come closest to addressing the issue, with a parliamentary committee recently proposing a new offence of distributing intimate images or video without consent.

In Britain, which also has no specific revenge porn laws, there is growing pressure to address the issue.

California recently made it a misdemeanour punishable by six months’ jail, but the legislation has significant loopholes.

New Jersey has anti-revenge porn laws, while Maryland, Wisconsin and New York are said to be considering new legislation.

Laws outdated

Despite significant concerns that some Australian laws have failed to keep pace with new technology – most notably surrounding sexting (sending explicit images via text message) – the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) insists police have the firepower to prosecute revenge pornographers.

An AGD spokesman cites the Commonwealth Criminal Code 1995, which makes it an offence to use the internet to menace, harass or offend as an example of legislation that may be used to prosecute revenge porn.

“This offence carries a maximum penalty of three years’ imprisonment,” the AGD spokesman says.

“This offence has been used in the past to prosecute threatening online comments, including in serious cases of cyber-bullying and, depending on the circumstances, may also apply in cases described as ‘revenge porn’.”

State and territory obscenity and indecent material laws could also be relevant in revenge porn prosecutions, the AGD says.

However, it’s understood there have been no Australian-led prosecutions for revenge porn or malicious reposting – and few anywhere in the world – despite clear evidence that Australian women are being targeted.

There have been few prosecutions anywhere in the world.

Ms Wells is among those who believes that current online menace or harassment laws, such as Australia’s Criminal Code 1995, are inadequate.

Opposition ready to listen

The federal opposition says it would be willing to consider new legislation if evidence emerges that the existing regime does not protect victims.

“While the Criminal Code Act 1995 covers the use of internet and social media to behave in a menacing or harassing way, if there is evidence that existing laws do not adequately protect individuals we are prepared to consider the appropriateness of increasing safeguards,” a spokesman for shadow attorney general Mark Dreyfus said.

There are no official figures for the prevalence of revenge porn or malicious reposting in Australia, but experts in the field of bullying and internet communications say it is increasing.

Jono Nicholas, CEO of youth advocacy group the Inspire Foundation, says young people are particularly vulnerable, especially those who engage in sexting.

Recent research, published by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (AMCA), shows that 18 per cent of 16- and 17-year-olds admit they have received a sext, while 13 per cent from the same age group admit they have sent a sext.

Once sexting photos or videos are sent, the sender can easily lose control of what happens to that content – especially if a relationship ends acrimoniously.

“It’s a real issue for young people – where things … happen within the context of a trusting relationship and then it breaks down,” Mr Nicholas tells AAP.

“For me, revenge porn … it’s a rarity, in the same way that the ADF Skype sex scandal was not representative of what’s going on in the ADF.

“But it’s no less harmful for that.”

Technology outpacing laws

Mr Nicholas says the prevalence of smartphones (Australia has one of the highest ownership rates in the world) and popularity of social media (12 million Australians use Facebook each month) has made it far easier to publish revenge porn or maliciously repost content.

“If you go back 10 or 15 years and the scenario of a celebrity sex tape, literally someone would’ve had to put that on a VHS and cart it around to various pornographers or put it out there,” he says.

“When you put that together with easy recording devices, easy publication devices, this area is a genuine concern for young people in terms of having something on the permanent record.

“It’s a situation no other generation has ever faced.”

The University of Melbourne’s Dr Lauren Rosewarne, an expert on sexuality, gender, feminism, public policy and politics, says revenge porn appears to be an extension of sex-based cyber attacks that have previously appeared in Australia, including social media sites critiquing women’s sexual performance.

“I think, like all awful things that happen online, while they are awful and traumatic for those involved, they are also very isolated cases and certainly no justification to do a bug sweep/hidden camera inspection of every bedroom you enter,” she says.

“That said, it does remind us of the importance of trust: that just as we should be mindful about trust related to STIs, contraception etc, that trust needs to be considered carefully if a brand new partner suggests bringing out the camera.”

AAP