What is a double dissolution election?

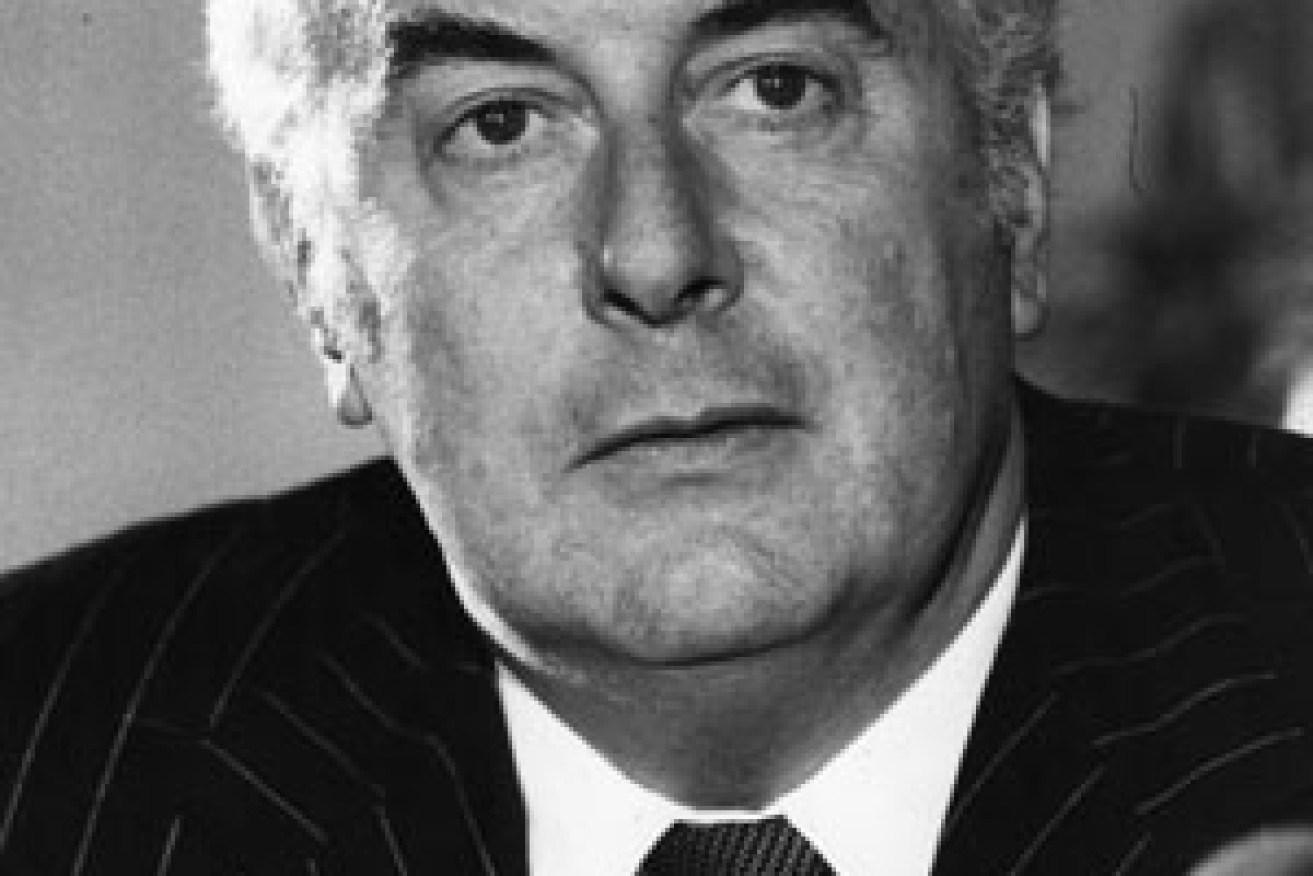

Gough Whitlam defeated Billy Snedden by double dissolution in 1974. Photo: Getty

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has put plans for a double dissolution election firmly on the table — a prospect that has micro parties quaking in their boots and voters scratching their heads.

On Monday, the PM recalled both houses of parliament for a joint sitting on April 18 to deal with a union corruption bill.

Parliament will consider the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC) legislation and if this does not pass the Senate, the PM will call double a dissolution election for July 2.

• Daniel Morcombe’s killer has appeal dismissed

• PM: July election up to the senate

• Coal mine could be Barnaby Joyce’s downfall

During an interview on Friday, Mr Turnbull blamed all this talk of dissolution on the Senate. If they’d just do what I tell them, we wouldn’t be having this conversation, he seemed to be saying.

“The only reason to go to a double dissolution is to resolve a deadlock,” he said.

Australia’s last double dissolution election came in 1987, when Bob Hawke defeated John Howard. Photo: Getty

That sounds like Mr Turnbull is using the threat of a double-D to get the Senate to do what he wants. If the Senate obliges, and Mr Turnbull calls a normal election, then all well and good. The double-D can go back to the dusty volumes of constitutional law where it belongs.

But if they don’t, and Mr Turnbull makes good on his threat, then here’s what you’ll need to know.

What is it?

In a normal election, every House of Representatives seat (150 of 150) is up for election, but only half the Senate (38 of 76).

In contrast, a double dissolution is when every seat in the upper and lower houses is re-elected.

The prime minister of the day can call a double dissolution instead of a normal election if he has the necessary trigger. More on that later.

Why use it?

A frequent criticism of the Senate is that it is “recalcitrant”. Which is a fancy way of saying it won’t do what the government wants — which is to shut up and pass its bills.

This is partly because only half the Senate is elected every three years. The remaining half are hangovers from a previous election when voters may have supported more non-government candidates, making it harder for the government to pass its legislative agenda.

The current Senate is particularly ‘recalcitrant’ because it contains a record number of micro party candidates, such as Ricky Muir and Jacqui Lambie, who take a lot of convincing to support the government. Hence Mr Turnbull’s reference to a “deadlock”.

The prime minister is keen to clear out these crossbenchers so he can more easily enact laws if he wins the next election.

Gough Whitlam defeated Billy Snedden by double dissolution in 1974. Photo: Getty

When can it be used?

This is the tricky bit. Mr Turnbull cannot call a double-D whenever he pleases.

In practice, the prime minister of the day must convince the governor-general that there is a necessary legislative trigger. There is some dispute among experts as to the finer points of what amounts to a trigger.

The simplest scenario is when the Senate rejects a bill once then rejects it again three months or more later. The Turnbull govt has such a trigger in the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Amendment Bill 2014, which has been rejected twice after the necessary delay.

But he must use this trigger before 11 May 2016 because of a time limit imposed by the constitution. If Turnbull doesn’t use the Fair Work trigger before 11 May, then he would need to find another trigger. And that’s where it gets murkier.

The constitution says a double-D can be held if the Senate ‘fails to pass’ a bill after rejecting it once. It mentions no time limit. The High Court has ruled that the Senate must have “reasonable” time, but also did not set a time limit.

The Senate has once rejected Turnbull’s construction industry watchdog bill and once referred it to committee.