Man Haron Monis: terrorist or deranged lunatic?

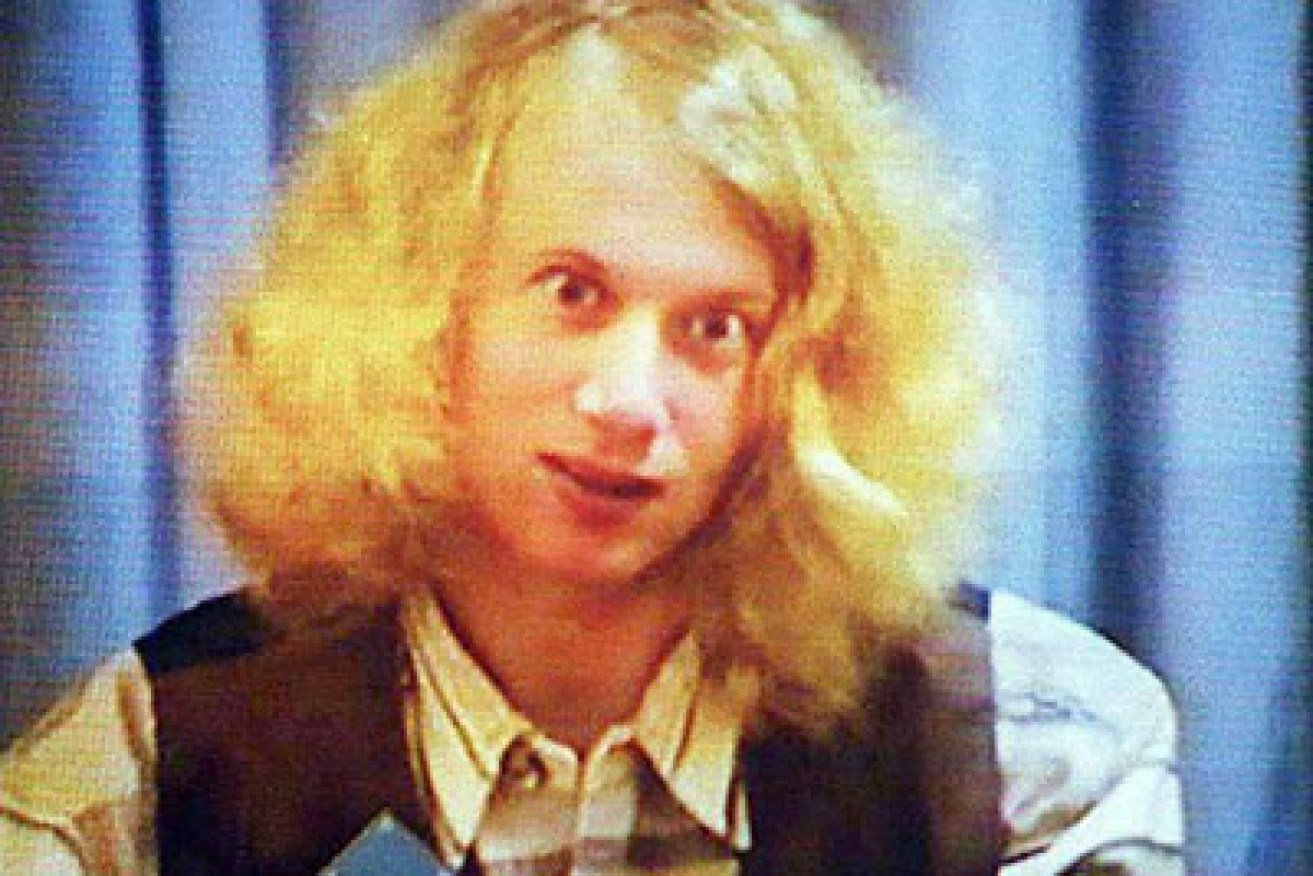

(FILES) File photo of Martin Bryant, the 28-year-old gunnman who massacred 35 people and injured 18 others during a shooting rampage in the historic settlement of Port Arthur on 28 April, appears on a video screen during his first court hearing in Hobart 22 May. Survivors and relatives of Port Arthur massacre victims were bracing themselves 27 April to relive a day of unbearable horror as they return to the historic site to commemorate its first anniversary on 28 April.

Man Haron Monis was many things: a refugee; an Australian citizen; a convicted criminal; a psychiatric patient; a wannabe bikie; but was he a terrorist?

Professor Bruce Hoffman of Georgetown University is pretty adamant that the answer to that question is ‘yes’.

Prof Hoffman argues that a distinguishing feature of Islamic State (IS) is that it employs a ‘big tent strategy’.

• Why tougher terror laws won’t stop ‘lone idiots’

• National security should not be above politics

• Australia’s obsession with anti-terror laws

Therefore, it embraces a multitude of potential terrorists: those willing to travel to take up arms with it in Iraq or Syria; radicalised individuals in the West; criminals; even, as Twitter users dubbed Monis in December, “lone dickheads”.

In fact, Prof Hoffman testified to the Sydney siege inquest that inspiring lone wolf attacks is key to the IS strategy.

This is a departure from previous terrorist organisations like the IRA and ETA who operated a strict central command structure. It is even different to that of Al Qaeda, which is selective in its recruitment policy.

Islamic State leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi has a policy of “whoever is radicalised is welcome”.

Prof Hoffman credits Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, the leader of IS, with a policy of “whoever is radicalised is welcome”.

The organisation does not need any prior knowledge of an attack. Its role is “to inspire, activate, animate individuals to engage in violence, to respond to its clarion call to violence” but the individuals are free to act on their own initiative.

Given that view, how does Prof Hoffman go about defining the Sydney siege as an act of terrorism?

He told the inquest: “You have to look at the act, which I have no doubt was a terrorist attack.”

In particular, Prof Hoffman rejects motivation as an element in the definition of terrorism: “Until we can peer into mens’ souls, we have no idea what motivated them.”

What does that mean for Australia?

The Australian definition of terrorism states an act of terrorism, or threat of action, must be done with two intentions.

Three people – including the gunman – were killed in the Sydney siege. Photo: AAP

Firstly, the action must be carried out to advance a political, religious or ideological cause. Secondly, the intention must be to coerce or influence through intimidation a government, the public or a section of the public.

That definition does not require a would-be terrorist to be a member of a group. The fact that Monis did not have direct contact with IS is irrelevant so long as he had a “political, religious or ideological” motive. The definition covers lone wolves.

Determining if an act constituted an act of terrorism does not require us to consider the mental health of the perpetrator.

As Prof Hoffman pointed out to the inquest, Ted Kacyznski, (the Unabomber) is generally considered to be a terrorist – despite mental health problems.

But not everyone agrees.

Counter-terrorism and radicalisation expert Kate Barrelle told the inquest she did not believe Monis acted like a terrorist during the siege, attributing some of his behaviours to poor mental health.

Actions which constitute terrorist acts – hostage taking, killing, etc – are also criminal acts. In Australian law, what differentiates terrorism from other crimes is the motive.

We are left with an intractable problem: we cannot peer into Monis’ soul. On the other hand, if violence in the pursuit of a political or ideological cause is not at the heart of a definition of terrorism what is there to distinguish terrorism from ordinary criminal acts?

What we can learn from history

Each of the attacks below could reasonably be considered an act of “terrorism” in a non-legal sense.

If motive is not an element of the offence of terrorism, then Martin Bryant and Peter James Knight might also be described as terrorists.

Criminal

Martin Bryant massacred 35 people and injured 23 others during a shooting rampage in the historic settlement of Port Arthur on 28 April, 1996.

Martin Bryant

Port Arthur Massacre, 1996

Pleaded guilty to murdering 35 people and injuring 23 others. He is currently serving 35 life sentences plus 1035 years without parole in the psychiatric unit of Risdon Prison, Tasmania.

The incident appeared like an act of terrorism. It is mass violence directed indiscriminately at a civilian population. But it lacks the motive element.

Lone wolf

Peter James Knight

East Melbourne Fertility Clinic Attack, 2001

Convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. He was armed with a rifle, homemade gags, kerosene and a pre-written note: “We regret to advise that as a result of a fatal accident involving some members of staff, we have been forced to cancel all appointments today”.

He shot and killed the security guard at the Clinic before being over-powered by staff and clients.

Unlike Bryant, Knight had a political motive: his anti-abortion position fits within the Criminal Code definition but his actions pre-date that legislation.

Terrorist

Faheem Khalid Lodhi was convicted in 2006 by a jury at the Supreme Court of New South Wales of three terrorism-related offences. At trial, Justice Anthony Wheally commented that Lodhi had “the intent of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause, namely violent jihad”.

For Justice Whealy, Lodhi demonstrated the necessary motive – “violent jihad” – but he was convicted of preparatory offences, namely: possessing a thing (a book) connected with preparation for a terrorist act; knowingly collecting documents (maps) connected with preparation for a terrorist act; and doing an act in preparation for a terrorist act.

Dr Fergal Davis is a senior lecturer in law and member of the Gilbert and Tobin Centre of Public Law at UNSW, Sydney. He has over a decade’s experience lecturing on parliaments, human rights, law and terrorism in Australia, Ireland and the UK and his research has been published internationally. He tweets about law and politics @fergal_davis.