Australia’s Bali Nine retribution

Getty

There was disbelief and an extraordinary outpouring of grief as Australia woke to the news that an Indonesian firing squad had executed Myuran Sukumaran and Andrew Chan.

The two convicted drug felons, and so-called ringleaders in an attempt to export eight kilograms of heroin from Bali to Australia in 2005, had spent 10 years on death row.

On the account of everyone who had spent time with the men, they had reformed.

• Now the AFP must explain its role in the tragic executions

• Bali Nine diplomatic fallout begins

• Indonesia executes Bali Nine pair Andrew Chan, Myuran Sukumaran

• Cruel, abhorrent’: anger, dismay at executions

The feeling in Australia is that Indonesian President Joko Widodo, a former furniture salesman, has ignored the persistent pleas from Australia to spare the lives of an accomplished artist and a Christian pastor.

It hasn’t gone down well.

All that remains now is to see the extent of the retribution Australia will take against Indonesia.

Already the Australian ambassador has been withdrawn for consultations, and ministerial contact between the nations has been suspended.

Australia’s foreign aid to Indonesia will be treated separately, said a clearly devastated Foreign Minister Julie Bishop, who has fought relentlessly to win clemency for the men.

A sombre Prime Minister Tony Abbott appeared alongside Ms Bishop in Canberra, calling the executions “cruel and unnecessary”.

His task was difficult – to soothe the broken-hearted with the promise of punishment for Jakarta while ensuring relations with Australia’s large northern neighbour are not irreparably damaged.

“I absolutely understand people’s anger,” Mr Abbott said.

“On the other hand, we do not want to make a difficult situation worse and the relationship between Australia and Indonesia is important, remains important, will always be important, will become more important as time goes by. So I would say to people yes, you are absolutely entitled to be angry but we’ve got to be very careful to ensure that we do not allow our anger to make a bad situation worse.”

Litany of offence caused

It’s hard to think what could make the situation any worse or the offence any greater.

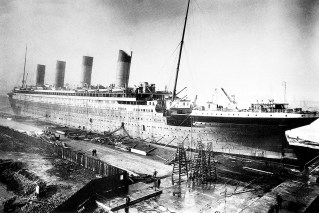

Indonesian armored police vehicles transporting the Bali NIne duo. Photo: Getty

Australians have felt offended not merely by the imposition of the death penalty against its citizens, abolished here in 1984 and last used in 1967.

They have felt slighted too by the refusal of Mr Widodo to heed Mr Abbott’s pleas for clemency based on the clear, unchallenged and moving self-rehabilitation of both Sukumaran and Chan.

The strong feeling at both a political and community level has been that Mr Widodo ignored Sukumaran and Chan’s rehabilitation because it was politically inconvenient to take it into account.

But as Sukumaran and Chan’s fate moved inexorably towards its end, the offence mounted.

There was the display of military might surrounding the removal of the men, both compliant, from Kerobokan Prison on Bali to their place of execution.

The images shocked Australians.

Removed from Kerobokan where they had built rehabilitation programs for fellow inmates, there was the refusal of the Indonesian Administrative Court to hear a challenge to Mr Widodo’s insistence that all drug felons on death row be executed, regardless of personal circumstance or rehabilitation.

There was also the delay in investigating claims that the original trial had been marred by corruption.

Last week, Ms Bishop noted with disdain that Sukumaran and Chan were given the mandatory 72 hours notice of their execution on Anzac Day, an emotional war commemoration which this year marked the 100th anniversary of the slaughter of thousands of young Australians at Gallipolli.

Emotion and anger peaked when on their last day with their loved ones, Indonesian authorities refused to allow the Sukumaran and Chan families to be driven to the ferry entrance, leaving them to fight their way through an unseemly barrage of reporters, police and sniffer dogs.

Indonesia seemed to understand the depth of anger when it reversed a decision denying Sukumaran and Chan spiritual advisors of their own choice to comfort them in their last few hours.

Relations marred

Relations between Australia and Indonesia have always been fractious.

Relations between Australia and Indonesia have always been fractious. Photo: Getty

In the past there have been disagreements over asylum seekers and tensions over revelations that Australia had tapped the phones of the Indonesian leadership.

But behind the diplomatic bluster and outrage, business has by and large proceeded as usual.

This time, the offence has reached deep into Australia’s cities, towns, suburbs and homes.

Very few have had no sympathy for the plight of the two young Australians whose crime was committed when they were very young.

As the inevitability of the execution drew closer, even those whose attitude was hardened seemed moved by the clear rehabilitation of the prisoners and the pleading of their families.

Vigils were held across the country.

The diplomatic reaction had been anticipated.

Withdrawing Australia’s Ambassador to Indonesia for consultation, symbolic though it is, is significant because Australia did not withdraw its Ambassador to Singapore after the 2005 execution of Australian citizen, Van Nguyen.

Retired diplomat Bruce Haigh said Australia should also ask the Indonesian Ambassador to Australia to leave and bring a case against Jakarta in the International Court of Justice for transgressing its own laws, by executing inmates whose legal appeals had not been exhausted.

Still available to the Australian government is the suspension of relations between the Indonesian Police and the Australian Federal Police, along with the imposition of trade sanctions.

Role of Australian Federal Police

Mr Haigh is not alone in calling for repercussions at home, particularly against the Australian Federal Police.

Retired diplomat Bruce Haigh calls for repercussions at home, and against the AFP. Photo: Getty

The AFP gave the Indonesian Police precise information about the Bali Nine, leading to their arrest, despite the fact the heroin they were trafficking was bound for Australia.

“The AFP should never have shopped them and having done so they should have done everything in their power to overturn this outcome. But they didn’t because their writ is to deal with the corrupt Indonesian police, naval and army personnel to prevent boats coming to Australia,” wrote Mr Haigh in a blistering commentary for News Limited.

“They are embedded; they are almost part of the system. We need to know why the AFP shopped the nine. The involvement of the AFP in these executions needs investigation.”

David McRae, an Indonesia expert at Melbourne University’s Asia Institute, believes Australia needs to show Indonesia there is a real cost to executions.

“That means expressing condemnation, suspending some co-operation for a period, and making future law enforcement co-operation conditional on the death penalty not being applied,” he told Fairfax Media.

There is at least one Indonesian who understands the depth of feeling and anger in Australia.

Ahead of the executions, former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono canceled a planned visit to Perth where he was billed as a keynote speaker at a conference on leadership.

For average Australians, there’s little love lost.

While Bali is a historically popular holiday playground for Australians, misunderstanding and scepticism is significant.

The relentless negative coverage of Indonesia’s intransigence on the clemency appeals by Sukumaran and Chan will no doubt worsen already frosty attitudes towards Australia’s neighbour.

A 2014 survey showed Australians feel greater warmth towards East Timor, Fiji, Papua New Guinea and even China, than towards Indonesia.

The prevailing view among ordinary Australians, albeit interviewed in the fog of grief, has been that they will never again visit Indonesia.

Monica Attard is a Sydney-based journalist, writer and former foreign correspondent, reporter and television and radio host at the ABC.