For survivors of disasters there can be a silver lining

“Mum, I’ve been in a train crash. People are dead.” The call from my young daughter Lija was startling. Was she alright? Where was she? What had happened?

In 2003 a train derailed in the Blue Mountains’ town of Glenbrook. Seven people, all in the first carriage, died. Many were injured. Lija was on that train.

“We’d gone into the front carriage,” she told me, “but there weren’t seats. That saved our lives.”

When the crash happened, Lija’s friend, a nurse, raced to see if he could provide assistance. He was too late.

• Adelaide Hills bushfire SA’s worst in 30 years

• Slow progress in AirAsia crash search

In the face of the disaster Glenbrook sprang to life. The community hall became a triage unit. A local army of volunteers provided cakes, scones, coffee and tea to stunned victims and their families. An array of priests and ministers materialised to provide counselling.

“I was in total shock – just walking around in circles,” reflected Lija. “I was worried about the dead people and felt a strong need to pray.”

“Healing took time,” Lija continued. “I did a ceremony with my friend throwing seven flowers (one for each death) on the tracks. I went to critical incidence debriefing.

“I went to the funeral of victims (a mother and child). I spoke on behalf of the victims. I had never done anything like that before. The funeral was a lovely honouring of the lives of the dead.

“I had to use the trains to go anywhere and I was scared – especially of riding in the first carriage.”

A Timorese coffee farmer plies his trade. Photo: Getty

It was eight years before she had the courage to ride up front again.

Mark Green, an experienced community development leader, believes that when the community works together over time even the worst disasters can lead to good outcomes.

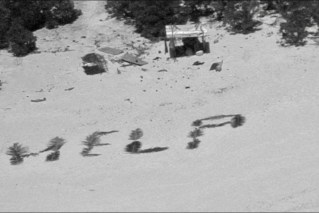

He related how in one geographical district in East Timor a big wind storm destroyed the community’s entire food crop, demolishing all this farming community’s income and food supply. They faced a long, lean and hungry season.

While the humanitarian response was to provide food and avoid starvation it was the community, with outside support, that created a longer term solution – a new system of farming that used trees to stop soil erosion and new farming methods that led to a better quality of life for everyone.

“Weather shocks can create a change in the community’s attitude to their entire environment,” Mr Green says. “Any humanitarian disaster leads to the community rebuilding itself.”

If this rebuilding is done thoughtfully the outcome can be wonderful.

Lija, now a happily married young mum living in a tight-knit coastal community, believes that her disaster experience gave her life added meaning.

“Because you are a survivor you feel like you need to live your life fully and do something meaningful because there are people who lost their lives at a very young age and will not get the opportunities you got,” she says.

“I had to heal myself first. I am grateful for every day. I count my blessing and work to build the community. There are others who aren’t here to be grateful.”

Tips for survivors

• Allow yourself to grieve – it is normal to go through a period of shock and fear – be kind to yourself

• Find and accept support – critical incidence debriefing, counselling, community support

• Find rituals that help you move through the pain and shock

• Be proactive – go to events such as memorial services and be part of the process

• Be an active part of the community – help others

• Use the opportunity to review your situation. In searching, you may find new ways forward that you might otherwise have missed

• Be grateful for what you do have