This is Bashir, the face of child detention

ABC

In most ways, 18-year-old Bashir is like any other teenager.

He was vice-captain at his high school in Sydney, likes to hang out with friends, and looks forward to studying commerce at university.

But this young man has one important difference to his classmates. He is one of hundreds of children who have been placed in detention as the government tries to stop asylum seeker boats arriving in Australia.

• ANALYSIS: Why Australia is failing on asylum seekers

• Indifference to asylum seekers starts close to home

Bashir Yousafi was 14 years old when he fled Afghanistan and the Taliban, risking death on a perilous boat ride to Australia, before spending nine months in detention.

“My father was killed by the Taliban and they were planning to kill me,” Bashir says.

He is softly spoken, but he raises his voice when he talks about the nine months of his life that were ‘wasted’ in mandatory detention.

Thursday was the International Day of the Child and marked 25 years since the United Nations created the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

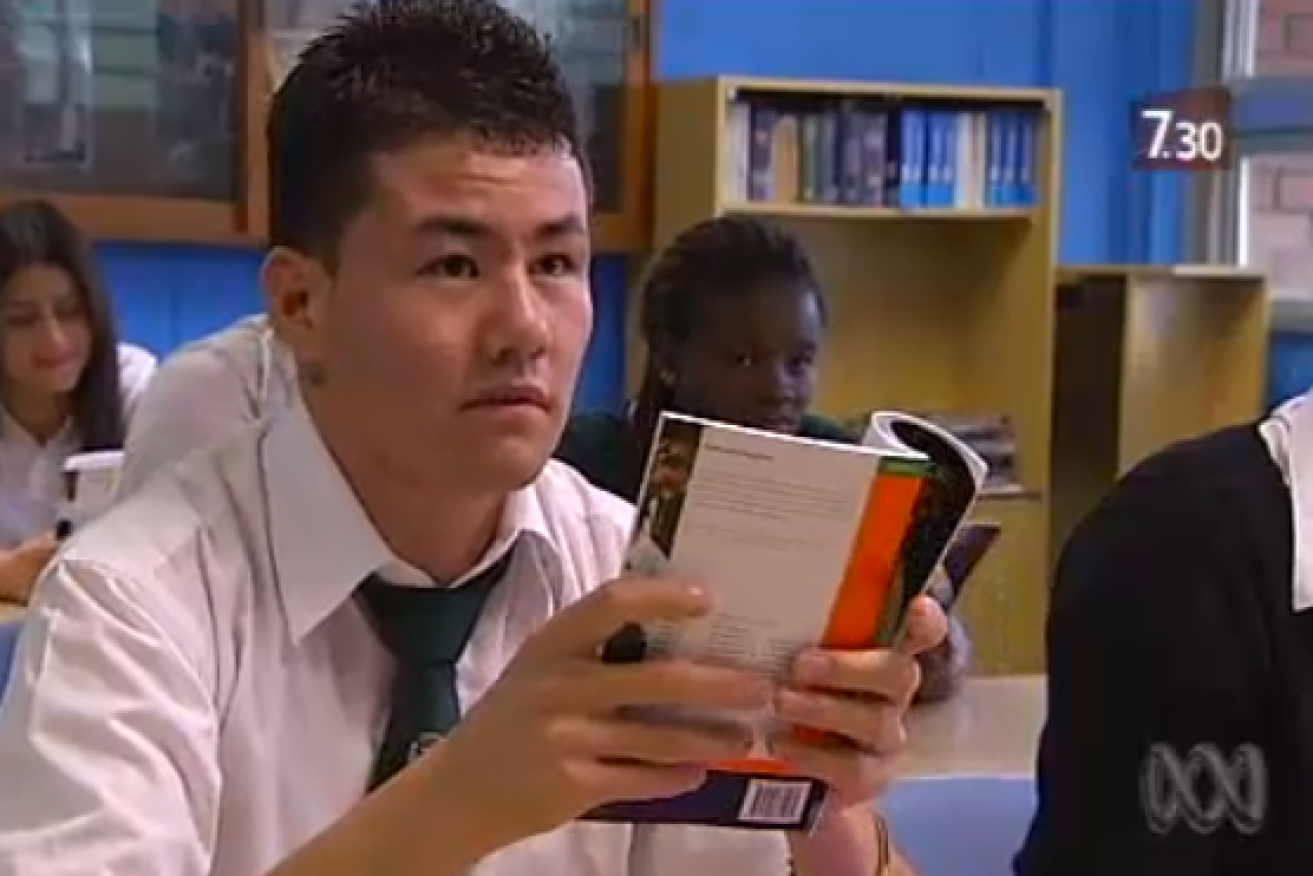

Bashir studying at school. Photo: ABC

Australia is a signatory to this convention, but human rights lawyers say Australia is in breach of international law and is failing its duty of care to children in detention.

While Australia has signed the convention, it is not enforceable in Australia.

There were 588 children like Bashir living in detention centres in June this year, according to the Department of Immigration.

Human rights lawyer and Chilout campaign coordinator Claire Hammerton says Australia has an obligation to children seeking asylum.

“Our view is that it is never in the best interests of the child to be held in closed immigration detention,” Ms Hammerton says.

“There are many other rights in the Child Rights Convention such as children having access to education, to play and recreation, that children be protected from abuse and maltreatment.”

While giving evidence at the Australian Human Rights Commission inquiry into children in detention, Immigration Minister Scott Morrison said placing children in detention was necessary to prevent them from dying at sea.

“I saw too many children die in the sea not to pursue the policies I’m pursuing,” Mr Morrison said.

He admitted that as a father of two young children, the immigration portfolio came with “emotional challenges”.

“The government is not going to allow a set of policies to be weakened that would see [an] Australian staring into the face of child corpse in the water again.”

Refugees have no choice but to flee their homelands, says Bashir. Photo: Getty

Despite Mr Morrison’s reasoning, Ms Hammerton says there is concern about the significant mental health impact of detention on children.

“Keeping children in closed detention facilities is extremely detrimental to their mental health.”

Bashir says he saw the mental health of people who had spent years of detention, and was ‘very scared’ he would become the same.

“When I was there, I saw people hanging and harming themselves. They had been in the detention centre for so long and I thought I would become like them.”

“I was so worried about myself. I couldn’t sleep. I wasn’t able to eat properly.”

While Bashir spent nine months in detention, the average amount of time a child spends in detention today is 349 days.

When asked if he would be where he is today if he had spent more time in detention, Bashir says “of course not”.

“Even though we are out of detention and we are in the community and we are free, we are still carrying the impact of being in detention,” he says.

The teenager, who represented Australia in Geneva at the Discussion for the Committee on the Rights of the Child, says asylum seeker children should be able to live in the community.

“It doesn’t make sense to lock kids up in detention. It won’t stop the boats.”

“Trust me, leaving their own country is not an easy decision. It’s the most difficult decision they will ever make.”