Australian economy at its lowest ebb in 27 years

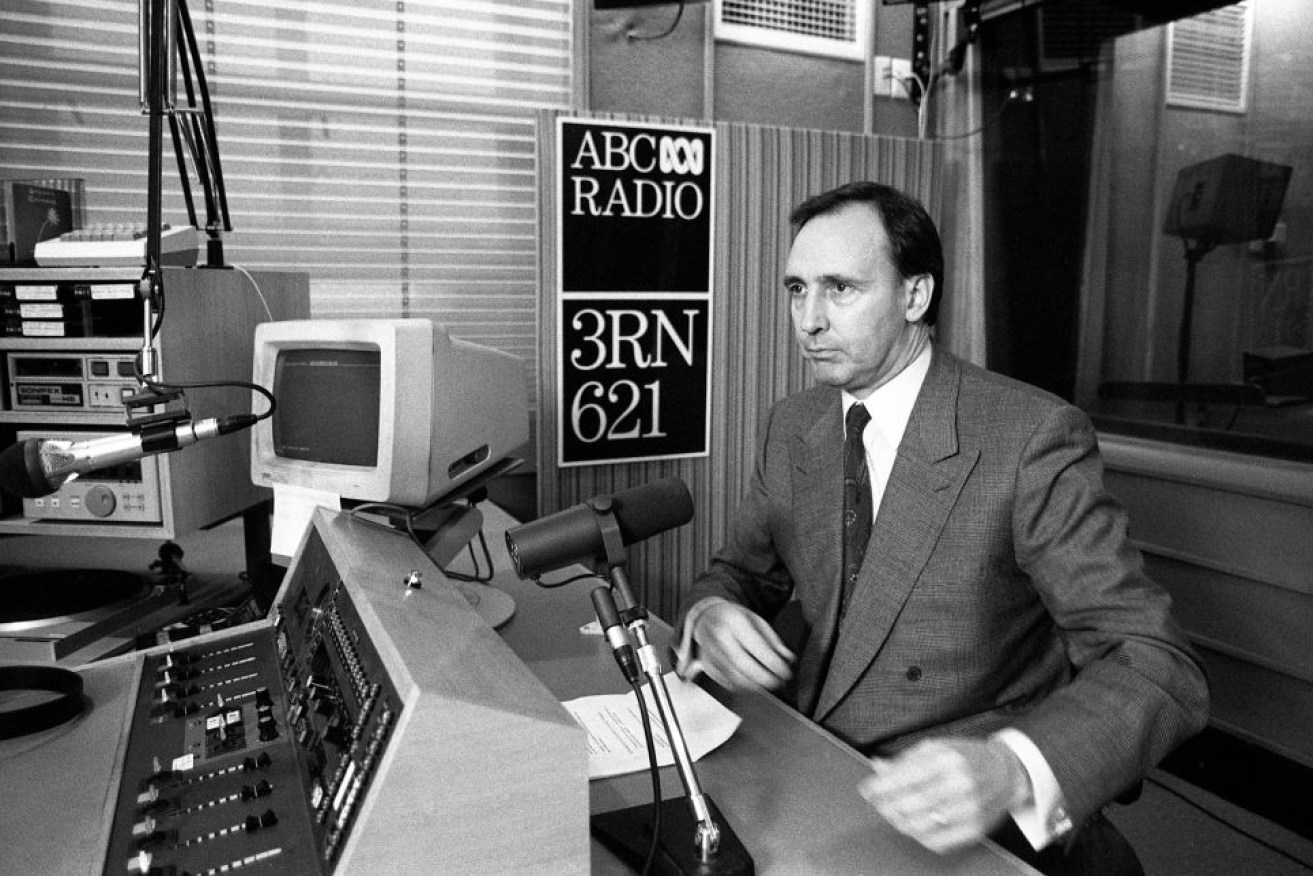

Aaaah, 1992: The last time the Australian economy was as dismal as it is now. Photo: Getty

The financial year ending in 24 days will be recorded as Australia’s worst since 1992, when the nation was struggling to recover from the 1991 recession.

Remember the repeated “strong economy” claim during the election campaign? It was a lie.

Yesterday’s national accounts showed economic growth in the year to March was 1.8 per cent. But there’s worse to come when we get the June count.

If the last quarter of the financial year averages the performance of the previous three quarters, GDP (gross domestic product) will have grown by just 1.3 per cent.

With population growth of 1.6 per cent, we are stuck in a “per capita” recession. No wonder the Reserve Bank governor has been publicly begging the government to help turn around the economy.

The last time our GDP growth fell below 2 per cent was in 2009 as the GFC hit, but even then we managed to do better at 1.9 per cent growth than the current score.

But these are only numbers.

Within the detail of the statistics, the reality for average Australians is worse news on wages growth and the outlook for the new financial year.

The government and RBA have tried to make much of a small uptick in the March quarter wages index to record annual growth of 2.3 per cent.

But the wages index is only one attempt at measuring what’s happening with household income.

The national accounts found average wage growth in the non-farm sector fell in the March quarter to 0.3 per cent from 0.5 per cent in the December period. In the year to March 2018, it rose by 1.8 per cent.

Yesterday’s Australian Bureau of Statistics’ publication casts a pall over the credibility of not only the government, but also the Treasury and, to a lesser extent, the RBA.

The federal budget published by Treasury on April 2 and endorsed by the Department of Finance in its PEFO (Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook) weeks later shows our key economic departments don’t have a clue about what the economy has already done, let alone what it might be about to do.

It looks like years of politicisation has run down Treasury to the point where budgets are prepared on patently specious grounds, such as the nonsensical assumption that our birth rate is about to start rising instead of falling. Those sorts of silly assumptions are necessary to make the better-than-reality figures the government wanted.

While the dogs were barking otherwise, Treasury – or Josh Frydenberg – kept claiming GDP growth this year would average 2.25 per cent. It won’t.

The RBA has been steadily revising down its year-to GDP growth assumption in its quarterly statements on monetary policy.

The bank bravely guessed 3.25 per cent in November, then 2.5 per cent in February and 1.75 per cent in May. The Martin Place mandarins will be busy now revising it lower still.

When the current quarter’s GDP is computed, it will replace the June 2018 score of a healthy 0.9 per cent.

The first three-quarters of this financial year have recorded growth of 0.3, 0.2 and now 0.4 per cent.

The economy started turning down in July and has stayed down. The main cause, as reported here and explained by the RBA, is weak consumer spending and weaker non-infrastructure construction.

Six years of sub-par wages growth, of real take-home wages shrinking, is hitting home after the reckoning was delayed by the illusion of greater wealth courtesy of the housing price boom.

This fundamental structural weakness in the economy is why the RBA’s Philip Lowe has been asking the government for five years to help, why just trimming interest rates further won’t make much difference and will take time to make any difference.

Individuals are, understandably, taking their own action. After years of running down the savings ratio to keep consumption running faster than disposable- income growth, people are trying harder to pay down debt and save more.

The result is that household consumption growth declined to 1.8 per cent in the March year and the household savings ratio increased to 2.8 per cent after bottoming at 2.5 per cent in the September quarter.

The danger the nation now faces is the “Paradox of Thrift” – while it makes sense for the individual to tighten the belt, it becomes a vicious cycle for the nation if everyone does it.

There has been anecdotal evidence of a pickup in confidence and spending after the election, but the bigger fundamentals of low wages growth and rising unemployment suggests that is unlikely to last.

We are underpinned to a degree by high iron ore prices (thanks to dam failures closing Brazilian mines), a services sector benefitting from international tourism and foreign students, population growth and state-financed infrastructure projects.

That combination is likely to enable us to avoid a real recession, but there is no reason to think Australia will have the promised “strong economy” in the new financial year.