Labor’s ‘back to the future’ plan for budget repair

Labor’s plan to claw back $14 billion in superannuation tax concessions from up to 180,000 wealthy Australians has been predictably greeted by the Coalition as ‘new taxes’ or ‘tax increases’.

Well, they’re not new. It was Peter Costello who made distributions from super funds tax free in 2006, so asking retirees earning incomes of $75,000 or more to pay a 15 per cent tax rate is actually reviving an old tax.

The other main provision, to cut the concession given to contributions to super funds from a 30 cent rebate to a 15 cent concession, is also not new.

• Revealed: the big losers in the AFL’s money war

• Will the RBA cut rates? All bets are off

• Labor reveals plan for superannuation changes

Bill Shorten: beginning to outline an alternative tax plan.

Labor’s change is to make that lower concession cut for somebody earning $250,000 rather than the current threshold of $300,000.

So are these tax increases? Well yes, obviously. However, a look back at the recent history of taxation at the federal level makes that ‘yes’ a bit more like a ‘no’.

To explain, it’s important to consider what the tax system is for – namely, providing public goods and services that the majority of voters think are best delivered by the public sector.

Australian voters like Medicare. They like roads. They like public universities, and so on.

Medicare: one of the services supported by the national tax take.

But funding these things is about more than balancing nominal tax revenues and expenditure, because two other factors make the tax/spending picture more complex.

The first is inflation. Labor has been attacked using raw, nominal figures. Senator Scott Ryan, for instance, has pointed out that spending grew by $100 billion between the last Howard government budget and Labor’s last budget in 2013.

That’s true, but let’s at least look at how prices have increased over that time – that is, adjust for inflation.

The second complicating factor is population growth, particularly of the politically determined kind – immigration.

Throw inflation and population growth into the mix, and it becomes clearer what sort of services can be delivered by any raw, nominal figure bandied about by either side of politics.

Voters will be forgiven, however, for not being overly familiar with such measures – politicians usually omit them, because nominal figures usually create more menacing or benign stories, depending on how they are used.

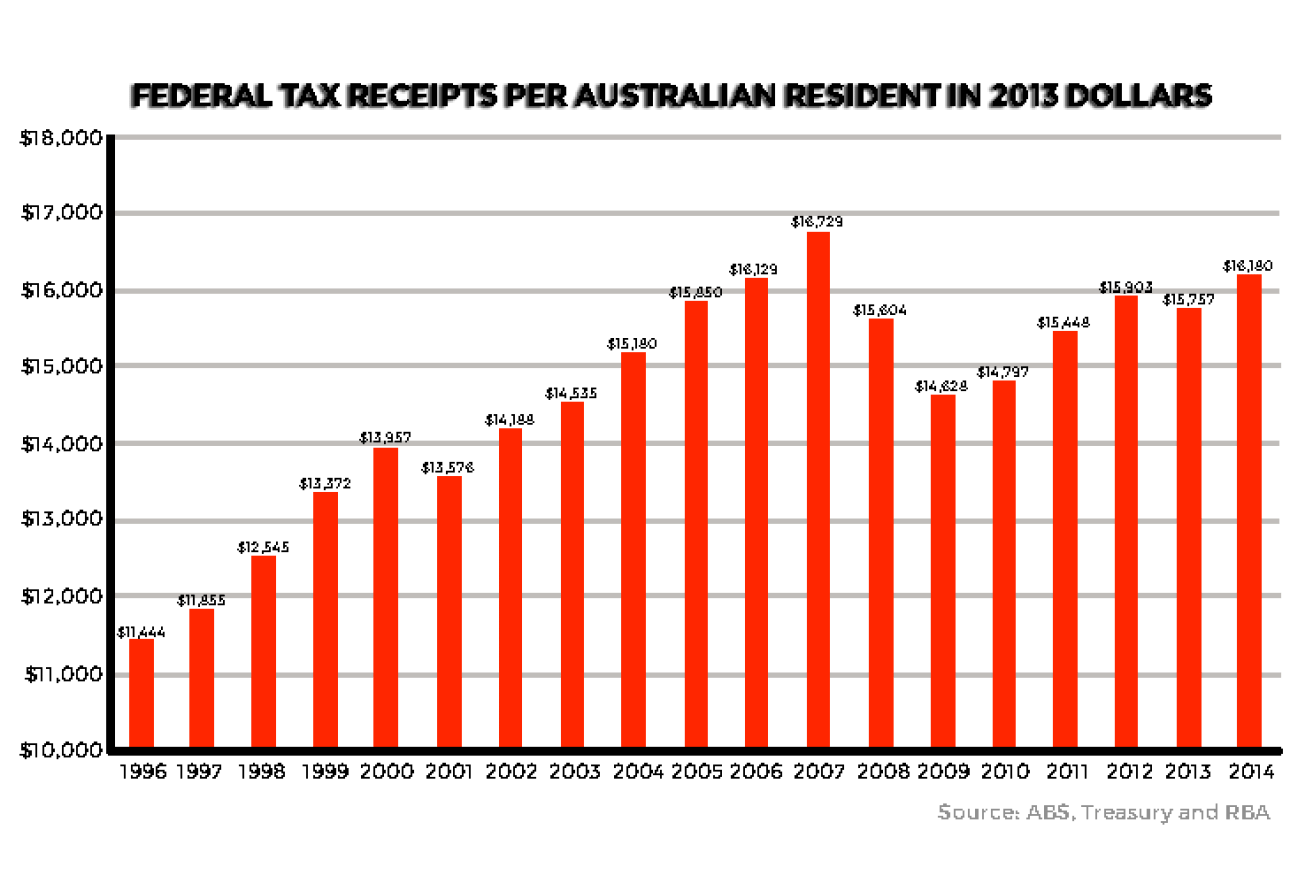

So in the chart below, keep in mind that the left-hand scale is actual buying power – that is, by converting tax receipts into ‘constant dollars’ we can get an idea of what level of services a government can provide with them.

And also keep in mind that as there are more residents in Australia, be they immigrants or home-grown, the same sized pie must be divided into ever-smaller slices.

The first thing to note in this chart is that between the end of Paul Keating’s tenure as PM and the end of John Howard’s tenure, Australia became a lot richer in real terms.

Tax revenues kept pace with the ever-richer Australia, and so using 2013 dollars as a benchmark, Howard could actually buy about 50 per cent more for each resident with his tax revenues than that misunderstood scrooge Keating.

Oh, and immigration was booming during that period too, reaching nearly 300,000 people in some years.

We got richer, we got more numerous, and the government still had more money to spend on each of us.

During and after the GFC, things took a turn for the worse. The Gillard government knew that voters were not likely to put up with cuts in services, so borrowed pretty heavily to keep things going – hoping against hope that revenues would recover and at some distant point we could even pay off the debt they had accumulated.

Well revenues recovered, but not as fast as Labor’s plans to spend that money increased. Then-treasurer Wayne Swan was tripped up by tens of billions of dollars in tax revenue write-downs and the Coalition’s ‘debt and deficit’ offensive began.

In a couple of weeks, we’re going to see how much revenue Treasurer Joe Hockey is collecting and what, if any, major cuts to spending he intends to make. That didn’t go so well in last year’s budget.

But whatever the numbers, the Coalition appears to be sticking with the line that the budget must be addressed on the spending side, and Labor is now digging in on the idea that it can be addressed on the revenue side.

Labor’s right about one thing – the Howard government was rolling in revenue.

However the Coalition also has a point – that with an ageing population and a slowing economy, it seems unlikely that we’ll be able to spend as much per Australian resident as John Howard did without increasing the national debt.

Sensible economic policy must surely lie between those two positions.

Labor is trying to raise taxes back to where they used to be. The Coalition doesn’t think that’s affordable.

Perhaps the side that will win that tug-of-war will be the one that stops using raw, nominal figures and starts having a serious debate about what level of spending is required to maintain the Australia voters grew to expect over the long boom of the Howard years.