Meet the ‘disturbing’ rise of virtual influencers faking their way into our Instagram feeds

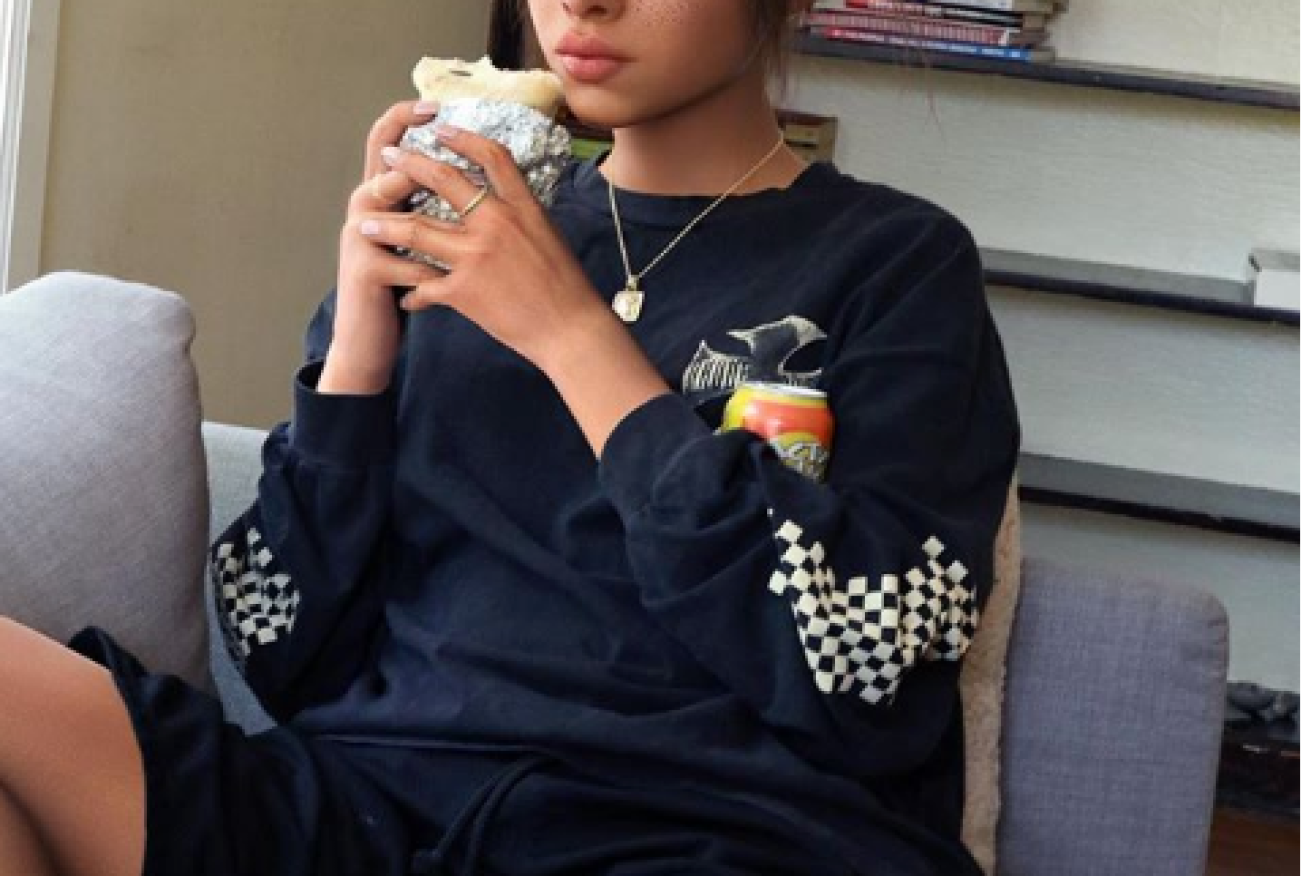

Miquela Sousa is a computer-generated influencer who supports Black Lives Matter and advertises for Prada Photo: Instagram

A new wave of celebrities are becoming the faces of global fashion brands, selling out concerts and gaining millions of followers on Instagram, but here’s the problem – none of them actually exist.

They are the computer-generated influencers that operate much like real-life ones do, with brands wanting to team up with them to tap into their fan base and seek endorsement deals.

But one expert has warned that the distinction between reality and fakery will become harder to discern, leading to increased body image issues among young women.

Virtual friend or foe?

Avatars have slowly been infiltrating our Instagram feeds since April 2016, when Miquela Sousa, known as Lil Miquela, a Brazilian-American ‘pop star’ posted her first photo.

The virtual model, who’s actually a verified Instagram user, captions her images with social justice hashtags like #BlackLivesMatter, and poses for fashion brands such as Chanel and Prada, has racked up more than 1.3 million followers.

Miquela’s photos claim she’s been to Coachella music festival, brags about her great time watching Beyoncé, and even has a song titled Not Mine on Spotify.

But, it doesn’t end there, the fake Instagram influencer, also has faux enemies, namely Bermuda – a virtual rival that sparked amid claims she hacked Miquela’s account.

Though her creator has never come forward, her Instagram following continues to soar, with users remaining fascinated about her virtual life.

Inspired by Barbie

Shudu, is billed as the world’s first virtual supermodel, with an Instagram following of 137,000.

Created by British fashion photographer Cameron-James Wilson last year, who was inspired by the Princess of South Africa Barbie doll to create a virtual model as way of promoting diversity in the modelling world.

“Basically Shudu is my creation, she’s my art piece that I am working on at moment,” Wilson, who has shot models including Gigi Hadid and singer Pia Mia, told Harpers Bazaar.

Earlier this year, Fenty Beauty – the make-up brand owned by pop star Rihanna – posted an image of Shudu wearing its striking orange shade of lipstick SAW-C – and it went viral. By April, Shudu had notched up almost 90,000 more Instagram followers.

The photo caused a storm among users, who were debating if the model was real or fake.

Upon realising Shudu was actually just an avatar, users expressed their devastation. “Imagine finding your girl crush, then finding out she’s not real all in one second,” said one Instagram user.

Shudu has also collaborated with major fashion labels, including Oscar De La Renta and New York-based lingerie company The Great Eros.

‘Majorly disturbing’

Body image expert, Sarah Harry, director of Body Positive Australia, said the rise of computerised Instagram followers was “majorly disturbing”.

“This trend is completely appalling, the images are showing flawless women who are perfect – and it’s sending the wrong message to young men and women,” Ms Harry told The New Daily.

She said it was shocking that Instagram verified the accounts of fake influencers.

“They’re not real and the creators are making money from images that are clearly objectifying women – these accounts shouldn’t be verified.”

Ms Harry said some images of Miquela were highly-sexualised and sent the wrong message to users.

“She’s half-naked and has her legs open in some photos – it’s just inspiring people to further pursue more sexualised images on social media.”

‘Not so peculiar’

But Dr Andy Ruddock, senior lecturer in communications and media studies at Monash University, told The New Daily the rise of fake Instagram influencers wasn’t as peculiar as some people thought.

“Audiences know what’s going on and they get pleasure engaging with the process, particularly in the construction of these avatar’s lives – it’s simply for entertainment value,” Dr Ruddock said.

He said the construction of a ‘pop star’ wasn’t something new.

“Whether it be an avatar or not, if you look at the discourse of The Voice and Australian Idol – that whole idea of manufacturing a pop star is evident and audiences are well aware of this.”