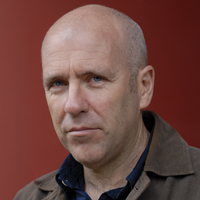

Toxic: Richard Flanagan exposes Tasmanian salmon industry’s rotten underbelly

Tasmanian salmon corporations are thieving from the future, writes Richard Flanagan. Photo: Getty

If we are what we eat, what our food has eaten in turn matters. Yet it’s easier to find out what you’re feeding your dog than what you’re feeding yourself when you eat Tasmanian salmon.

Should you search the murky filth of a salmon pen to discover what constitutes the millions of feed pellets that drift down, you would quickly find yourself enveloped in a growing darkness. A veil of secrecy, green-washed and flesh-pink-rosetted, was long ago drawn over the methods and practices of the Tasmanian salmon industry, from its inexplicable influence over government processes to its grotesque environmental impacts. But the biggest secret of all is what the industry feeds its salmon.

From the beginning, the outsized environmental damage the industrial production of Tasmanian salmon creates has been outsourced to where it can’t be seen – under water – and to countries so far-off few have any idea that the problems and suffering of these countries are connected to the Tasmanian salmon industry.

In the early decades of farming, Tasmanian salmon – a carnivore in the wild – were largely fed on anchovy-based fishmeal and fish oil imported from Peru.

The fishmeal industry on which the rise of the ‘clean and green’ Tasmanian salmon industry was built left the sea surrounding Peru’s capital of anchovy fishing, Chimbote, contaminated, its coastline badly degraded and the town seriously polluted. According to Professor Romulo Loayza, a biology professor at the National University of Santa in Nuevo Chimbote, there are around 53 million cubic metres of sludge in the seas around Chimbote, residual waste from the fishmeal factories, which in some parts reach more than two metres in height.

In an investigation for The Guardian, Andrew Wasley observed that the Chimbote fishmeal factories’ insatiable demand for anchovy ‘impacted on the sea’s natural food chain, and reduced stocks of previously plentiful species fished for human consumption’. He describes Chimbote in 2008 with black smoke billowing from the fishmeal factories drifting through the streets, ‘obscuring vision and choking passers-by. It looked like the aftermath of a bomb.’

In ‘one poor community … more than a dozen women and children gathered in the dusty, unpaved street to vent their anger at pollution from the fishmeal plants: they claimed they were responsible for asthma, bronchial and skin problems, particularly in children.’

The protesting Peruvian women and their sick children is one image of Tasmanian salmon that won’t appear in any glossy history of the industry’s rapid rise or its marketing of itself as environmentally responsible. Nor will that of the sea lions slaughtered by local anchovy fishermen, who saw them as competitors for a dwindling resource, their corpses scattered along a rubbish-strewn Chimbote beach, ‘quietly rotting in the sunshine’.

Today, Tassal claims it uses 1.73 kilograms of wild fish to make one kilogram of salmon. In other words, a lot more protein to make a lot less. Yet a major study found that 90 per cent of fish caught globally that were not used for human consumption were ‘food-grade or prime food-grade fish’.

Fishmeal and fish oil are the products of global supply chains of staggering complexity and opacity, subject to constant change because of weather, natural catastrophe and politics; captive to a thriving black market in which fishmeal from one country with unac- ceptable practices can be illegally traded to another and then on-sold as that second country’s product.

A recent report by the Netherlands-based Changing Markets Foundation linked leading global fish-feed giants BioMar and Skretting – which, along with Ridley, are the feed suppliers to Tasmania’s salmon industry – to ‘illegal and unsustainable fishing practices’ that were ‘accelerating the collapse of local fish stocks’, ‘driving illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing’ and ‘wreaking environmental damage around production sites’.

The salmon industry rejects such reports, claiming that its fishmeal and oil are legitimately and ethically sourced. It points to the fishmeal industry’s certification standard, known as the International Fishmeal and Fish Oil Organization Global Standard for Responsible Supply (IFFO RS) – IFFO being the fish-meal producers’ own global association. Or it was, until last year when, in the wake of the Changing Markets Foundation report and subsequent controversy, it was rebranded as the MarinTrust Standard to distance itself from IFFO. Accordingly, the IFFO MarinTrust Standard has been condemned as ‘a sustainability smokescreen’. If the standard is not independent, as its critics claim, it’s difficult to believe it is trustworthy, given the conflict of interest.

Salmon farming is about creating protein by stealing it from others. Far from being a sustainable solution to the global collapse of wild fishing stocks, fish farming is driving overfishing, with an estimated 25 per cent of fish caught globally being used for aquaculture. Alassane Samba, the former head of research at Senegal’s Oceanic Research Institute, has warned that depleting fish at the bottom of the food chain ‘could lead to a collapse of the marine ecosystem’.

In at least one case, a Namibian sardinella fishery, that nightmare is already reality, with the fishery collapsing entirely and the void left by the sardinella being filled with jellyfish – the first case in the world where fish were replaced with jellyfish.

More salmon for us means less food for others. Far from feeding the world today, Tasmanian salmon corporations are thieving from its future.

This is an edited extract from Toxic by Richard Flanagan. Published by Penguin Books Australia. RRP $24.99.