Australian researchers’ genetic breakthrough in diagnosing early prostate cancer

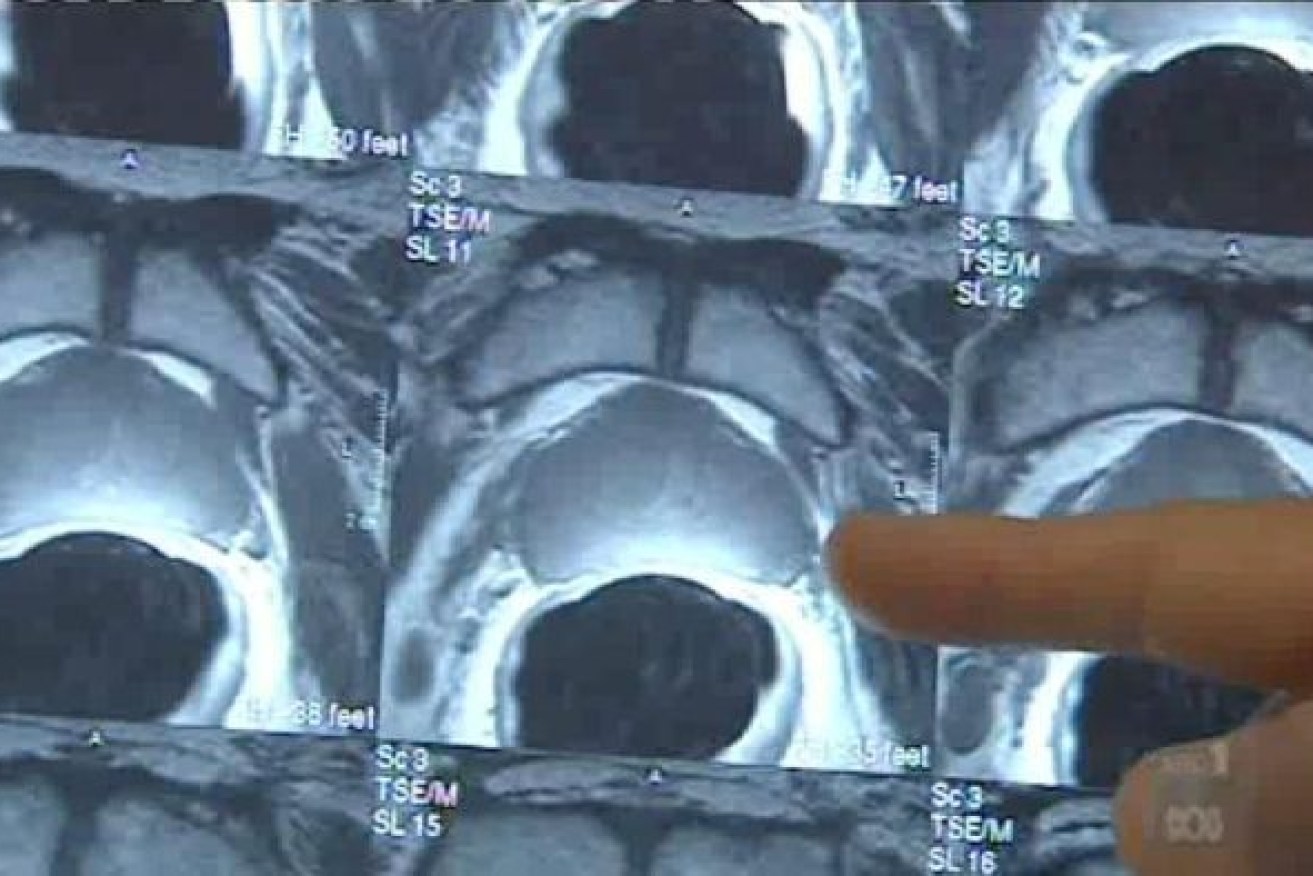

Prostate cancer is the second most-common cancer in Australian men. Photo: Getty

Twenty years of delving into the human genome has delivered a major breakthrough for a team of Australian scientists seeking a means of diagnosing the most aggressive prostate cancers.

The painstaking discovery of new epigenetic biomarkers, or DNA features associated with abnormal cell division, is the work of senior staff at Sydney’s Garvan Institute.

Combined with traditional clinical tools, the group believe their findings will allow doctors to predict whether men will go on to develop more metastic and lethal forms of the disease and devise better treatment plans.

Globally, prostate cancer is the second most common cancer for men. Following diagnosis, about 50 per cent of patients develop metastatic cancer during their lifetime.

Typically, this takes 15 or more years but a small percentage of men develop a fatal, metastatic form at a much earlier stage.

By identifying those who may belong to this category, lead researcher Professor Susan Clark said clinicians could readily begin more aggressive treatments.

“There’s a need for men with prostate cancer to have more personalised treatments guided by the nature of their tumours,” she said.

“They can’t get that without new biomarkers that can better predict the risk of developing the lethal form the disease.”

Life or death indicators

The research to identify them involved one of the longest and most comprehensive molecular studies of prostate cancer progression known.

A bank of biopsies maintained for 20 years at Garvan and St Vincent’s Hospital, allowed the analysis of samples from 185 men who had their prostate removed due to a cancer diagnosis in the 1990s and 2000s.

The team then tracked the number who survived and those who died, some more than 15 years later.

They examined their genomes and identified 1420 regions specific to the prostate cancer where they could see epigenetic changes – marks on the DNA known as methylation.

Eighteen genes were further studied, with one standing out: CACNA2D4.

“There’s very little known about this gene and it’s not typically profiled, so we really need to understand how the methylation process may suppress the gene’s activity,” said study author Dr Ruth Pidsley.

The team, all of whom work conjointly with the University of NSW in Sydney, have made the sequencing data available for further research.

The next step will be to determine whether the biomarkers can be detected in blood samples at the first instance.

-with AAP