Maths is about to hand out its ‘Nobel Prize’ – here’s why you should care

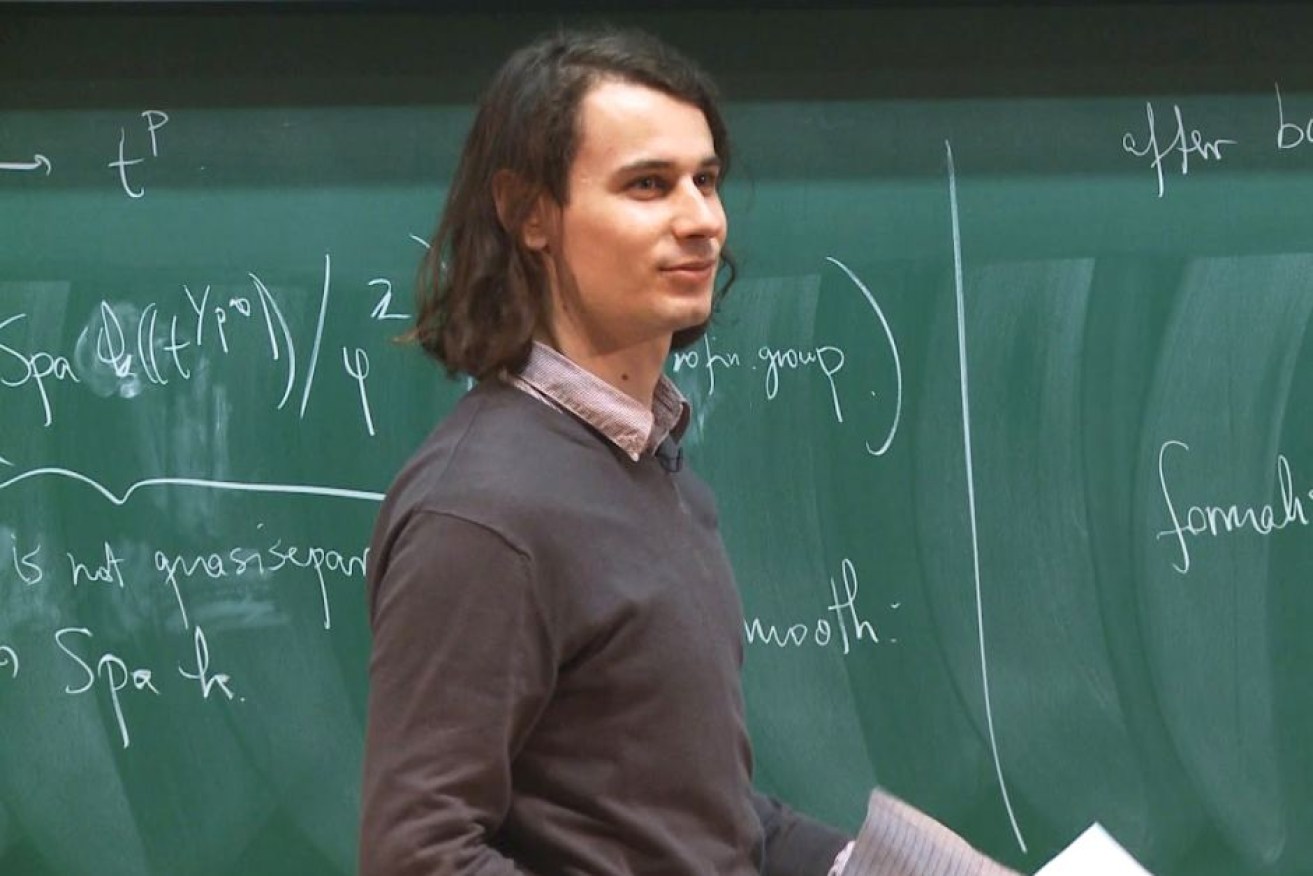

Peter Scholze is regarded as one of the finest mathematical talents of his generation. Photo: YouTube/IHÉS

Mathematics is popularly considered to be a solitary activity practised out of the public spotlight, but every four years that perception briefly changes.

On Wednesday night Australian time, the discipline’s brightest minds will gather in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where less than a handful will receive its most coveted prize — the Fields Medal.

As highlighted in the movie Good Will Hunting, the Fields is the closest thing maths has to a Nobel Prize, and it has been growing in profile in recent decades.

“It’s an award for career achievement, not one-off discovery, for mathematicians 40 or under,” said broadcaster, author and self-professed maths nerd Adam Spencer.

“It’s the highest individual prize in mathematics and so every four years when the International Mathematical Union gets together to give away two, three or four Fields Medals, there is a frisson of excitement.”

Maryam Mirzakhani was the first female and the first Iranian to win a Fields Medal. Photo: Stanford University

In 2014, the Iranian mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani became the first female to receive a Fields Medal for her outstanding work in geometry.

The professor, who died in 2017, spent much of her time thinking about the complex maths involved in the ways billiard balls interact around differently shaped tables.

But the Fields Medal has not been without controversy, and a closer look at its history reveals a collection of characters who defy the stereotype of mathematicians as individuals out of touch with the ‘real’ world.

Why should we care about the Fields Medal?

Great scientific breakthroughs often have unexpected consequences.

For example, cryptography that secures data transmissions relies on facts about prime numbers that were discovered without any thought that they would turn out to be ‘useful’.

“It’s research for the sake of research that then eventually becomes of great benefit to us all,” Spencer said.

“Some people make breakthroughs in pure mathematics that might sit around for decades or even centuries before we suddenly find an amazing relevant practical application for that mathematics.”

Maths is so prevalent throughout the modern world that it is easy to overlook the tremendous role it plays, influencing everything from traffic light sequences to stock market trades.

“The most brilliant mathematical minds end up shaping our world directly and our lives indirectly in ways that we probably never even realise our happening.”

Are any Australians in the running?

Only 56 people have won a medal in the prize’s 82-year history, including the Adelaide-born Terry Tao, whose prodigious talent led to him being dubbed the ‘Mozart of maths’.

By the time he was nine years old, he was already attending university courses and is today a professor at the University of California in Los Angeles.

Australian mathematician Geordie Williamson is a specialist in geometric representation theory. Photo: University of Sydney

You can’t bet on who will win the Fields Medal, but if you could, Peter Scholze would be an odds-on favourite this year. The young German is renowned for his work at the intersection of two disciplines — geometry and number theory.

According to Spencer, Australia is in with a chance of securing its second Fields Medal, thanks to the University of Sydney’s Geordie Williamson.

Earlier this year, he became the youngest academic member of the Royal Society at the age of 36.

“He’s a brilliant mathematician. It would not be a shock if Geordie picked up a Fields Medal,” Spencer said.

“He is certainly good enough.”

Has anyone ever refused a medal?

In 2006, the reclusive Russian genius Grigori Perelman — who proved an outstanding problem in a branch of maths known as topology, which deals with shapes and surfaces — is the only winner to have declined the medal.

He is understood to have been dissatisfied with the mathematical community following an academic dispute over credit for his work.

Cedric Villani was elected tot the French parliament. Photo: Getty

Political activists have also been honoured, including Stephen Smale — who was outspoken against the Vietnam War — and Alexander Grothendieck, who is widely considered to be one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century.

In 1966, Grothendieck refused to travel to Moscow to collect his Fields Medal in protest against the Soviet Union’s imprisonment of two writers.

In 2017, another Fields Medal winner Cedric Villani took a political turn and was elected to the French Parliament, representing Emmanuel Macron’s party En Marche.

So, again, why should we care?

Earlier this month, the Federal Government announced every high school across the country would have to employ science and maths teachers who have studied those subjects at university level.

The move is aimed at boosting the number of high school graduates who go onto study STEM subjects at university.

“There’s a realisation in government and the general community that we certainly need our share of talented, brilliant nerds in this country to carry us through the next few decades,” Spencer said.

“This century will be built by mathematicians, whether it’s computer coding, algorithms, machine learning, artificial intelligence, app design and the like.

“We as a country, can either choose to be on that bus or spend the rest of this century begging the intellectual property that they’ve developed.”

That is one of the strongest practical reasons why we should all take an interest when the Fields Medals are handed down, Spencer believes.

“If we’re going to give away Olympic gold medals,” he said, “for being really good at running fast … and if we’re going to let people win world cups of football and have billions of people watch the grand finals … then we should also acknowledge the magnificence of the mathematical mind.”

–ABC