Note to self: A pandemic is a great time to keep a diary

A search for “Coronavirus Diary” on Google yields 910,000 results.

News outlets like the Guardian, The Atlantic and The New York Times have chronicled an increase in personal record-keeping.

Whether for future historians, self-care or to relieve feelings of isolation, we are in the middle of a diarological moment.

And today’s diaries aren’t just handwritten reflections in bound notebooks.

They might be social media posts, video entries or visual collages – so long as they are regularly updated over an extended period and personal in nature, they fit the bill.

The secret is in the repetition, and the pledge that drives it: ‘Dear diary, what a day it’s been.’

On the look out

The word diary entered the English language in the late 16th century, via the Latin word, diarium, which comes from dies, meaning day. The diary asks us to attend to this day.

Diary-keeping sharpens observational skills, so it is no wonder then that cultural institutions have begun projects to crowd-source details of what otherwise might be quite banal aspects of our lives.

The State Library of Victoria has a Facebook group, Memory Bank, where posts of shopping lists and sourdough recipes have given way to more melancholy images of closed shops and empty streets in the CBD – a collective chronicle both hyperlocal and universal.

The State Library of New South Wales subtitles its Diary Files an “online community diary”, and currently contains nearly 1000 entries, searchable by keywords.

School, time, home and COVID are among the most commonly written words, and the greatest number of contributions come from Sydneysiders between 10 and 15 years of age.

Video “lockdown” diaries can also be viewed online, via BBC Reel, or listened to through Corona Diaries, the interactive open source project that collects audio stories from around the world.

Social researchers have identified the diary as a tool to capture the impact of the pandemic on daily life.

UK sociologist Michael Ward began his research through CoronaDiaries, where 164 participants ranging in age from 11 to 87 submit entries in a variety of forms.

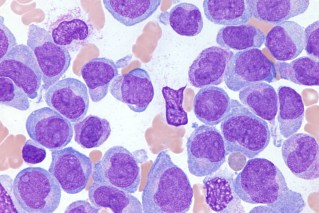

Ward suggests: These entries are able to highlight the multiple different lives behind the dreaded numbers we hear announced each day.

Vic Lee self-published a Corona Diary. He sold 2500 copies and donated some proceeds to charity.

Famous diary keepers

Most of us can name some famous literary diarists of history – Samuel Pepys, Virginia Woolf, Adrian Mole.

When we stray far beyond this list, it is often the times, rather than the writer, that make the diary notable.

There is Lena Mukhina’s perspective on the Siege of Leningrad, 13-year-old Anne Frank’s account of the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands and the poignant scratchings of Sir Robert Scott’s on the day he perished: “For God’s sake, look after our people”.

Nelson Mandela’s desk-calendar notes, kept in prison, speak to extraordinary experiences under extreme conditions.

Diaries from the 1918 influenza pandemic came into their own as more than ephemera for historians and scientists in 2020.

For a book-length account, we can look to Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, about life in London in 1665 – bearing in mind the author was only five years old at the height of the epidemic, so it is likely a factual-meets-fictional rendering.

Diary-writing serves broader society, and can help individuals make sense of difficult times.

Interviewed for this story, psychologist Robyn Moffitt told us: “From a psychological perspective, keeping a diary is a really useful (and evidence-based) way to engage in healthy self-monitoring of thoughts, feelings, and behaviour … writing things down as they happen can provide some objective evidence and perspective on the frequency and severity of different events, and we can use this to correct distorted thinking.

“The process of writing itself can also be quite therapeutic. It can allow us to process and reconstruct past events, problem-solve, and create new meanings, and in some ways this makes it similar to psychotherapy. Psychotherapy is often referred to as the “talking cure”, and writing can provide similar therapeutic benefits (the “writing cure” perhaps)?”

What makes it a diary?

The turn of the 21st century saw a resurgence of the diary in public reading events such as Mortified, Salon of Shame and our own experiments with The Symphony of Awkward.

It might be argued that social media has since overtaken the diary as a means to chronicle one’s life. Indeed, there is crossover in the ways lives are shared and curated across different media, from the handwritten diary to blogs.

The ritualistic structure offered by the personal diary can be repurposed in digital spaces. The notion of publicly committing to post something – an image, a video, a song – every day offers another way of marking out time when every day is Blursday the fortyteenth of Aprilay.

We have experimented with each recording a sound a day, collected from the few spaces we were still able to inhabit.

A diaristic practice, whether written or not, supports us to stay in the moment, as psychotherapists and life coaches exhort us to do.

And it’s never too late to start diarising. Here are some tips:

Decide on your platform

Digital or analogue? Decide on your medium. The written or spoken word? A photo? A sound? A song? Choose something that pleases you (a special pen, a fancy notebook) to heighten the experience.

Make a vow

Make an entry every day, or on a set number of days for four weeks. 28 days is said to be a good target if aiming to break or start a habit – though it may take longer.

Make time

Set aside time at the same hour each day to capture your experience.

Rinse and repeat

Carpe diem. Seize the day!

The Symphony of Awkward is hosting a free online forum on September 24 to discuss diary practices.![]()

Peta Murray, Vice-Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Media and Communication, RMIT University; Kim Munro, Lecturer, RMIT University, and Stayci Taylor, Lecturer, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.